On the 25 August 1851, an ordinary young boy finds himself in 2 Bridge Street, Westminster, for an out-of-the-ordinary apprenticeship. Today, nearly two centuries later, his musical instruments can be found in some of the most prized heritage collections in England. Stephen Quilter’s story is yet another example of the usually uncredited greatness that Foundlings can achieve.

Stephen’s early life

Stephen Quilter (Foundling Number 19949) was born on 13 February 1837 and admitted to the Foundling Hospital on 27 May 1837 after a petition from his mother, Harriet Ball. In this, she tells the story of how she met Stephen’s father, Joseph Kemp, whilst she was working as a cook for Captain Davis at 4 Camberwell Road, London. They met when Joseph, working as a stable man in the back of Captain Davis’s property, was running some errands for her employer. Joseph promised marriage before he ‘seduced’ her, but Harriet officially reported that she now had ‘no knowledge of him’. Harriet then went on to work for Mrs David of Store Street, who provided a character reference for her petition, describing her as a ‘well-behaved and respectable woman’.

The day following his arrival at the Foundling Hospital, Stephen was baptised by J. Forshall in the Hospital’s chapel. Shortly after, he went to live with Hannah Hodge, a wet nurse in East Peckham, Kent, and her husband and four children. The Foundling Hospital Archive has no records of his time at the Hospital after he returned from Kent until his apprenticeship to a musical instrument maker in 1851.

Stephen grew up in a musically vibrant environment because music was an integral part of the Foundling Hospital. In the 18th century, the famous German composer George Frideric Handel composed the Hospital’s anthem, ‘Blessed are they that considereth the poor’, and conducted his most famous composition, Messiah, in the Hospital’s chapel to raise funds. From the 1760s, Foundlings were taught to sing psalms and hymns for Sunday services in the chapel, which visitors could attend.

An important milestone in music teaching at the Hospital came with the establishment of the boys’ band in 1847, which nudged many to pursue careers in military bands. Therefore, it is no surprise that the Foundling Hospital’s musical environment would pave the way for Stephen’s own musical career.

In August 1851, Stephen began his apprenticeship with Henry Potter, a musical instrument maker, at 2 Bridge Street, Westminster. In 1858, Stephen received 5 Guineas for completing his apprenticeship, a grant commonly given by the Foundling Hospital, and he set up his own business.

Music in Britain in the 19th century

In the 19th century, orchestras increased in size in response to the demand for a wider sound and tonal range to try and capture the drama and expressionism of the Romantic period. This was achieved primarily by expanding the woodwinds and brass sections. What this meant for a small musical instrument maker living in London was an increased demand for woodwinds as orchestras now required double the number of flutes and clarinets to capture the essence of the Romantics.

Furthermore, in the Victorian period, sheet music became more accessible to the public. Therefore, it became common for middle- and upper-class families to own a piano and encourage their children to learn musical instruments.

Additionally, the establishment of the Royal Military School of Music in 1857 solidified and standardised the role of military bands in the Army and Navy. Most regiments had their own band, which typically consisted of percussion and wind instruments.

This meant that there was an increase in demand for musical instruments, particularly woodwinds, making it a prosperous environment for an up-and-coming woodwind maker.

Family life

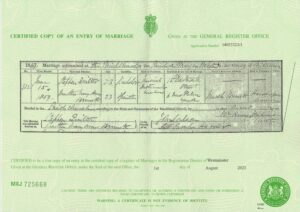

In June 1859 Stephen married Martha Mary Ann Bennett (born in Salisbury, Wiltshire). On their marriage certificate, whilst Martha recorded that her father was a hairdresser from Salisbury, Stephen did not write any details of his heritage.

By 1861 they were living in 15 Dartmouth Street, near the Houses of Parliament, in a dwelling they shared with four other families, whilst Stephen worked as a musical instrument maker. Their first child, Ellen, was born there, and they welcomed two more children after moving to Chelsea: Walter and Anne.

Around 1867, the family moved to 51 Ferdinand Street, Chalk Farm, London, where four more children were born: Thomas, Stephen, William, and Martha. In the 1870s, his wife Martha began working as a ‘retailer of confectionary and tobacco’ and Stephen started producing musical instruments for the military.

The census returns show that the Quilters regularly had a lodger in their house. In 1881, the lodger was Alfred Payne, a railway clerk of similar age and profession as Stephen’s eldest son Walter. The following year, his daughter Ellen married Payne.

It is important to mention that in 1891, their address changed to 3 Ferdinand Street as there was a ‘formal order’ for the renumbering of Ferdinand Street. The Cox family moved to two rooms in the upper floors of 5 Ferdinand Street, which they shared with Stephen’s children. John Cox was working as a ‘maker of pianos’ along with William Quilter, Stephen’s youngest son. They seem to have been Stephen’s employees at the time. By 1901, William was no longer living at home, and Stephen had started employing two other members of the Cox family, George and Albert, the former describing himself as a ‘piano stringer’ (responsible for inserting strings into a piano and tuning them). However, by 1906, the Cox family seems to have moved out as Stephen is listed as the owner of 3&5 Ferdinand Street. He retained his workshop and shop on the lower level of his properties.

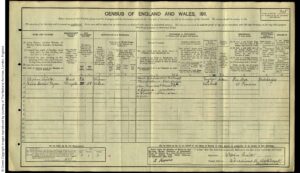

The 1911 census shows Stephen as a 74-year-old widower, still living there with Ellen Rachel Payne, his oldest daughter, a widow. In it, he gives us the most descriptive account of his profession:

‘Wood Wind Musical Instrument Manufacturer.

Flutes, Clarinets, Oboes, Bassoons, Drums, etc.

Repairer. Also Maker in Ebonite, Metal, Silver or Gold.’

In the following census, Stephen was still working as a musical instrument maker at the age of 84, which he could have continued until his death in 1923. His long life remains a true testament to the greatness that a person can achieve regardless of the circumstances in which their life started.

Stephen’s instruments in English museums

Stephen Quilter’s instruments can be found in the prestigious collections of Oxford University, the Horniman Museum, and the Royal College of Music. All the instruments in these museums are inscribed with the maker’s address: 3&5 Ferdinand Street, St Pancras, London.

- The Bate Collection of Musical Instruments at Oxford University has three clarinets and a transverse flute. One of the clarinets dates to around 1900 and belonged to Philip Bate, the man who donated the first instruments of the university’s collection. The transverse flute and another clarinet are dated between 1890 and 1925.

- The Horniman Museum has two clarinets, one from 1905 made from brass and coccus wood (granadilla), along with its mouthpiece, ligature, mouthpiece cap and bell (which goes at the end of the instrument to improve the sound). The Horniman’s other clarinet is a clarinet in C (dated 1875-1900) that has a golden star emblem inscription above and below Quilter’s details.

- The Royal College of Music Museum has a clarinet in B flat dated c.1900 with a flower-shaped mark around the inscription. The flute in this collection is dated between 1883 and 1890.

Image gallery – click to enlarge

- Horniman Museum: Stephen Quilter clarinet in C, object 2004.1000/422.211.2. Used with permission.

- Horniman Museum: Stephen Quilter bass clarinet (all parts), object 2011.61. Used with permission.

- Horniman Museum: Stephen Quilter bass clarinet (upper joint), object 2011.61.5. Used with permission.

- Horniman Museum: Stephen Quilter bass clarinet (lower joint), object 2011.61.6. Used with permission.

- Horniman Museum: Stephen Quilter clarinet (bell), object 2011.61.7. Used with permission.

- Royal College of Music Museum: Catalogue record for Stephen Quilter clarinet in B flat, object RCM0326C19. Used with permission.

- Royal College of Music Museum: Catalogue record for Stephen Quilter flute, object RCM0326FL22. Used with permission.

- Marriage certificate of Stephen Quilter and Martha Bennett, 1859. © Crown Copyright. Used with permission.

- Census return for 3 Ferdinand Street, London, 1911. © Crown Copyright. Used with permission.

Bibliography

Foundling Hospital Archive

Petitions Admitted: A/FH/A/08/001/002/046/015/a1-b2

General Register: A/FH/A/09/002/005/286

Baptism Register: A/FH/A/14/004/001/614

Apprenticeship Register: A/FH/A/12/003/003/056

Camden Archives

St Pancras London Rate made in 1901

St Pancras Ratebook Ward 2, April 1906

St Pancras Ratebook Ward 2, April 1911

Other sources

Beskin, Alison E. (2013) Music in Victorian London Collective Nostalgia and the Cultivation of National Tradition.

Daniel, Ralph T. (n.d.) Western Music: establishment of the Romantic idiom.

The Open University. (n.d.) Cultures of Brass Project.

Copyright © Coram. Coram licenses the text of this article under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 (CC BY-NC).