18th Century England was a trailblazer in the international clockmaking industry, producing high-profile innovators such as John Harrison and George Graham. Thanks to this growing trade, some of the boys in the Foundling Hospital were able to establish successful careers through their apprenticeships in clock and watch making. One such foundling was No. 624, John Crowdhill.

Luck of the draw

John was admitted into the Foundling Hospital on 10 August 1750. At this point in time, the Hospital employed the ballot system for admissions, where mothers drew a coloured ball out of a bag to determine if their child would be admitted. John’s mother was clearly lucky and drew a white ball, and after passing his health checks, John was allowed into the Hospital.

Although John had already been named ‘Charles Harris’ by his mother, he was baptised under his new name on 12 August 1750. He was then sent to a wet nurse in the countryside before returning to the Foundling Hospital in 1754. A month after he returned to the Foundling Hospital, he was inoculated for smallpox. He had a case of measles in 1755, but managed to remain healthy for some time after this.

John’s education

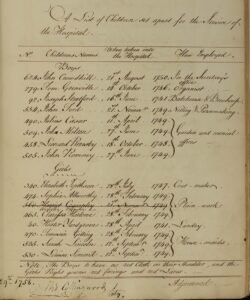

From an early age, John appeared to be a quick learner and an intelligent boy. When he was just eight years old in 1758, he was listed among other children who had been ‘set apart for the Service of the Hospital’ as working in the Secretary’s office, presumably helping with basic administrative tasks which would require a good level of reading and potentially writing. Most of the other children on this list were set apart for more manual tasks, such as working in the garden or the laundry, so John must have been noted as being particularly gifted to be chosen specifically to help in the Secretary’s Office.

- A/FH/A/03/005/003/107 – Sub-Committee Minutes, 25 November 1758. Click to enlarge.

In 1760, the Sub-Committee minutes noted him again in an examination of the children’s reading progress, which stated that he ‘reads well’. These minutes also contain a review of the material that was used for teaching the Foundlings how to read, which included ivory letters, the Royal Battledore (a pasteboard used to teach the alphabet), the Little Lottery Book (a book containing a catalogue of animals and fruits) and the Infant Tutor (a book aimed at teaching young children about basic scientific concepts). The minutes then go on to describe the three ‘Forms’ children were ranked by depending on their reading ability: ‘good Readers, Indifferent Readers and Spellers’. John seemed to be in the top ranking for his reading ability.

Unfortunately, John’s education was interrupted at the beginning of 1761, and he was sent to Westerham Foundling Hospital to recover from his ‘declining state’. Many children at the London Foundling Hospital were sent to Westerham if they were seriously ill, most likely because it was considered a healthy area due to its clean country air and because of its proximity to London compared to other branch hospitals. Thankfully, John recovered from his illness and returned to the London Foundling Hospital three months later in better health.

The cogs begin to turn

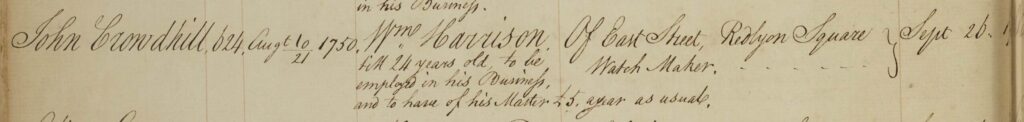

On 26 September 1764, aged 14, John was apprenticed to William Harrison of Red Lyon Square, London, as a watchmaker. Harrison was a Governor of the Foundling Hospital and was elected to the Royal Society in 1765 for his work on the ‘sea watch’ or the H4 marine watch. He was also the son of John Harrison, inventor of the marine chronometer, and often travelled with his father for his experiments on determining longitude while at sea.

A/FH/A/12/003/001/064 – John Crowdhill’s Apprenticeship Record

We do not know for certain why William Harrison chose John Crowdhill to become his apprentice. It is likely that John’s clear academic skill helped him to land this position in such a prestigious watchmaking workshop. He was employed until he was 24 years old, during which time he would have witnessed the Harrisons’ development of the H5 chronometer. This was demonstrated to King George III in 1772 and was awarded a cash prize for its contribution to maritime innovation. This model would be John Harrison’s final work.

This development in watchmaking would undoubtedly have enhanced John Crowdhill’s experience at the workshop and may have inspired his decision to start his own watchmaking business. We know that he continued in the industry long after his apprenticeship, as in 1785 he is listed as a watchmaker in his marriage to Catherine Parker. Kent’s Directory for 1791 lists a watch and clockmaker named John Crowdhill in Bedford Row, close by the workshop where he did his apprenticeship.

A potential product from his shop is a pocket watch from 1787 inscribed with the name John Crowdhill, which could be the former Foundling apprentice. Although the pocket watch seems typical of its time at first glance, it has a few unusual features that indicate John’s incredible skill. For example, the ruby cylinder escapement, an innovation first used by French watchmaker Abraham Louis Breguet, is quite rare for English watches in the 18th century and was expensive to use in a watch. This not only shows that John continued to engage with developing techniques in his trade, but also that his business was successful enough for him to afford such features.

It is clear that John remained a successful watchmaker long after his apprenticeship, no doubt thanks to the high-quality tutelage he received from William Harrison and the other watchmakers in his workshop.

Pocket watch image gallery – click to enlarge:

All photos from cogsandpieces.com

Bibliography:

Foundling Hospital Archive

Billet Book: A/FH/A/09/001/008/051-052

General Register: A/FH/A/09/002/001/069

Baptism Register: A/FH/A/14/004/001/048

Sub-Committee Minutes: A/FH/A/03/005/003/107; A/FH/A/03/005/004/153-4: A/FH/A/03/005/004/200

Westerham Hospital Register: A/FH/A/10/008/001/006

Apprenticeship Register: A/FH/A/12/003/001/064

Other sources

London Metropolitan Archives: London and Surrey, England, Marriage Bonds and Allegations, 1597-1921: DL/A/D/24/MS10091E/98

The Royal Society: Certificates of Election 1765: EC/1765/06

Kent, Henry. (1791). Kent’s Directory, 59th Edition. London

Copyright © Coram. Coram licenses the text of this article under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 (CC BY-NC).