Charged with high treason for ‘degrading a coin of the realm’, a desperate mother placed her two youngest sons in the Foundling Hospital.

A family shattered

Friday 13 January 1758 was a devastating day for Margaret Larney and her family. Margaret sat in the dock of the Old Bailey and listened as the judge handed down the death sentence. Margaret was found guilty of filing a gold coin – the practice of physically filing gold dust from the currency, which she would have sold on to supplement the family’s small income. Court records show that a witness had accused her of filing one guinea, a coin that contained a quarter ounce of gold.

Margaret was employed in washing, and carrying out simple needlework as a plainworker. Her husband Terrence was a laborer and occasionally worked for a hatter. Their mouths were not the only ones needing to be fed – their four children lived with them in a room in Holborn, London.

Margaret had every reason to expect that her punishment would be less severe than death. While the charge of high treason levied against her could carry this penalty, it was far more common to be transported to America. It is possible that Margaret’s background figured in the judge’s decision. She was Irish, Catholic, and poor and therefore a subject of contempt in an England whose ruling class were hostile to ‘popery’. Indeed, the records of Newgate Prison commended her for attending Anglican services but noted that she ‘held this good purpose no longer than till the next visit from a priest of that persuation, whose undue (not to say) tyrannic influence over their people, depends on their ignorance of the sacred scriptures’.

Terrence responded to the verdict urgently. On the day following the conviction, two of the children – James, aged 5, and Elizabeth, aged 3 – were submitted for a pauper examination at St Martin in the Fields parish, and were admitted to the workhouse there. It seems likely that Terence took this route because he would not have been able to look after the children as well as earn a living.

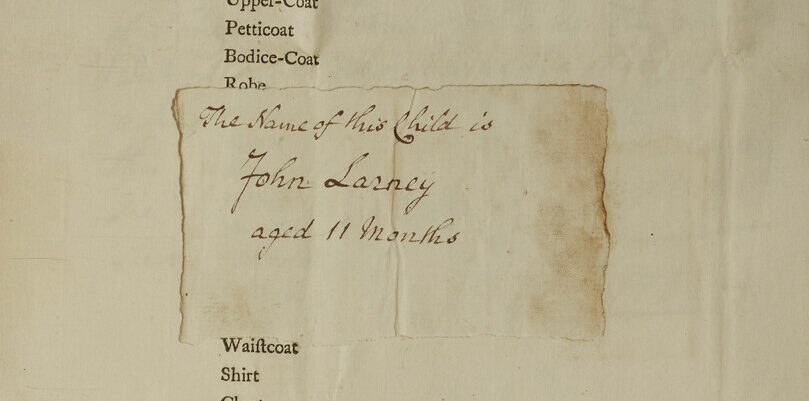

On 25 January, the youngest child, John, was admitted to the Foundling Hospital, aged 11 months. This was during the General Reception period, when the Hospital had to accept any baby brought to the porter’s lodge, as a condition of a Parliamentary grant. John was older than regulations allowed (three months or younger), but perhaps an exception was made because of his mother’s circumstances.

Amidst this, the date of Margaret’s execution was delayed because she was found to be pregnant. This was known as ‘pleading the belly’. It was determined that she would remain in Newgate Prison in the City of London until the child was born. Meanwhile, Terrence appears to have absconded with their oldest child, who was around 14 years old.

George Millet’s story

Elizabeth and James, who were admitted to the workhouse, illustrate the dire chances of survival for abandoned children in the 1700s. They both died within months – Elizabeth in May and James in July.

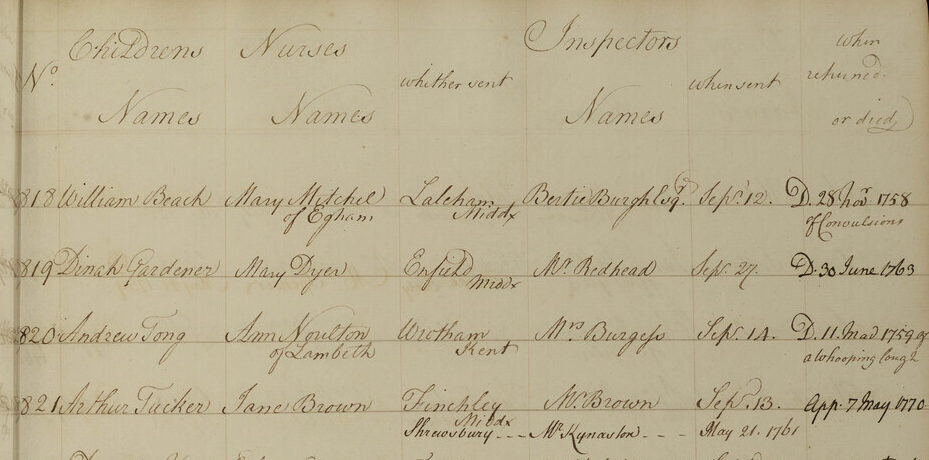

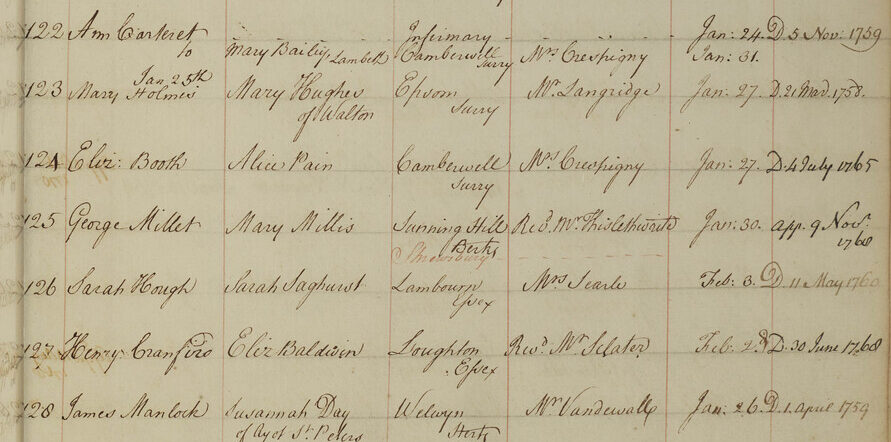

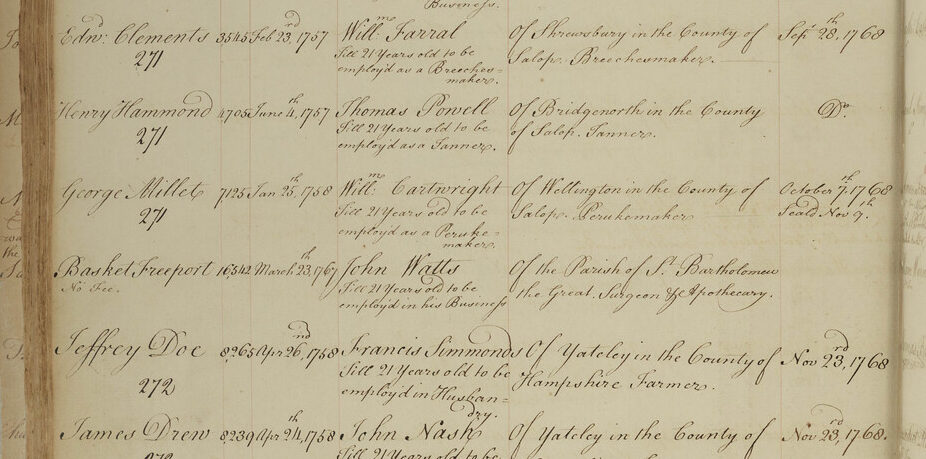

In contrast, John had better life chances after being admitted to the Foundling Hospital. He was given the number 7125 and a new name, George Millet. This was standard practice at the Hospital – the new name gave each child ‘a fresh start’, unburdened by their parents’ history. Five days after being admitted, George was sent to live with a dry nurse, Mary Millis, in Sunning Hill, Berkshire.

We know that at some point, George returned to the Hospital because his next appearance in Coram’s Foundling Hospital Archive records that he was sent from London to the Shrewsbury branch hospital in October 1768. The following month he was apprenticed to a peruke maker in Wellington, Shropshire, until the age of 21. A peruke was a men’s wig, made of long hair, which was fashionable amongst the upper classes.

William Beach’s story

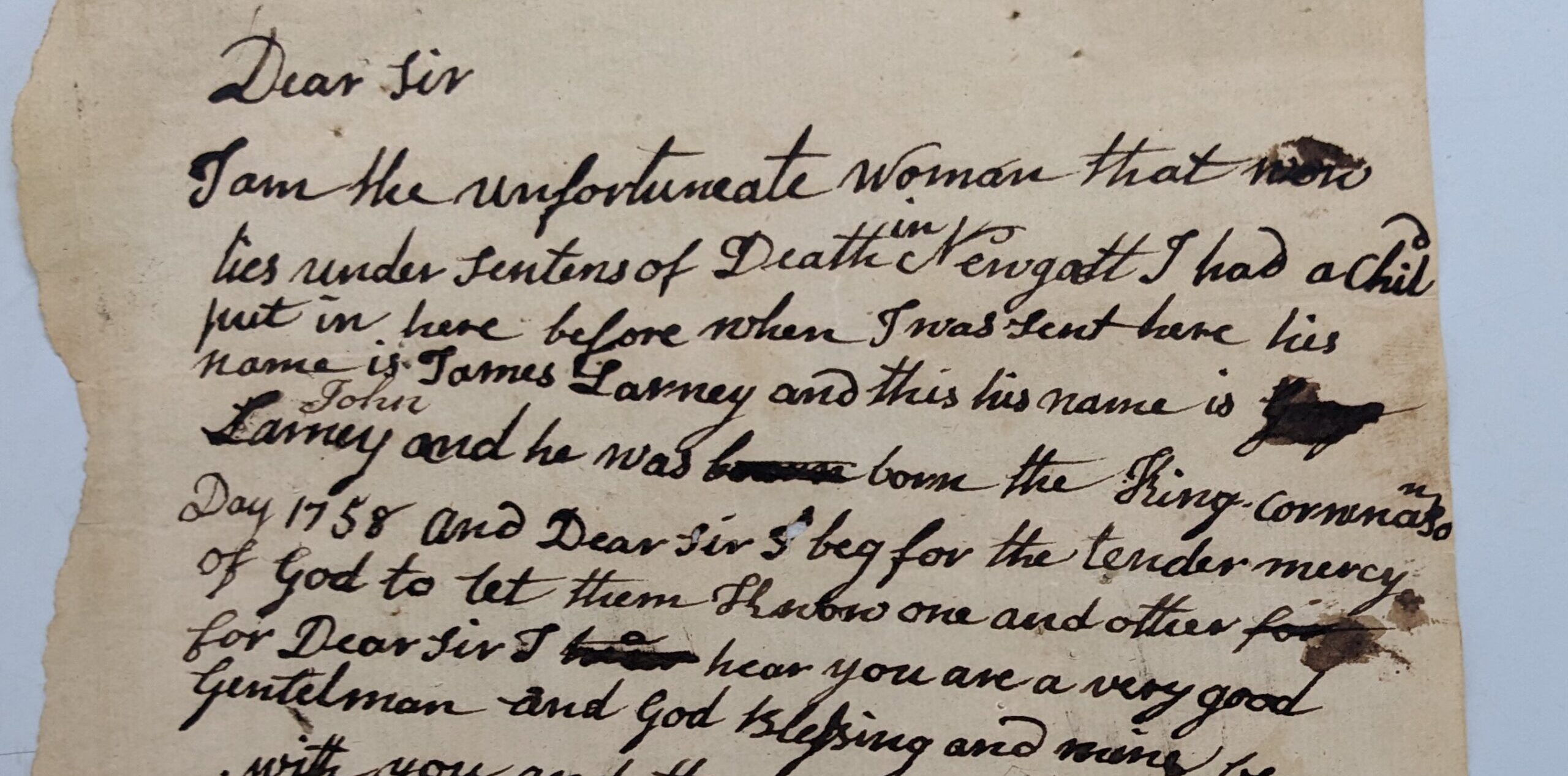

Throughout her time in Newgate Prison, we can imagine Margaret wondering about the fates of her children. We do not know if she learned of Elizabeth and James’ deaths. Thanks to a letter in the archive, however, we do know that she was aware of John’s admission to the Foundling Hospital and of her hope that the child she was carrying would enter the Hospital too. Margaret’s letter reads:

I am the unfortunate woman that now lies under sentens of death in Newgatt I had a child put in here before when I was sent here his name is James Larney and he was born the King Coronation Day 1758 and Dear Sire I beg for the tender mercy of God to let them know one and other for Dear Sir I know you are a very good gentleman and God Blessing and mine be with you and they for ever Sir I am your humble Servant

Margaret Larney

It is likely that Margaret would not have known how to write and was supported to write this letter by someone else. Indeed, the name of the child is wrong – James went to the workhouse and John to the Hospital. Perhaps her scribe misheard. Many words have been crossed out in the letter; perhaps, Margaret was reconsidering her words as she dictated it.

No doubt she was relieved to learn that her baby would be admitted to the Foundling Hospital. She obviously imagined that the boys would be introduced and would spend afternoons running around the playing fields with one another. She was not to know that the Hospital’s policy of giving children a fresh start meant that their relationship would never be revealed to them, however alike they may have looked.

Margaret’s baby was admitted to the Hospital on 12 September 1758, given the name William Beach and the number 9818. He was sent to a wet nurse, Mary Mitchel, in Egham on the day of his admission, but died of convulsions there two months later. His brother George would never have been told about him, or their mother, who was executed on 2 October 1758.

Copyright © Coram. Coram licenses the text of this article under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 (CC BY-NC).