Content Warning: This article contains references to physical and sexual abuse, which readers may find distressing. Find more information on Coram’s help and support signposting page.

During the period known as the General Reception (1756-1760), the Foundling Hospital admitted thousands of babies, which led to the establishment of branch hospitals outside London. Shrewsbury was the second branch hospital to be opened and the second largest in terms of the number of children cared for.

Establishing the Shrewsbury hospital

The decision to establish a hospital in Shrewsbury was made in 1758. The town met a number of criteria for branch hospitals set by the London Hospital’s Governors, including being seen as a healthy and relatively inexpensive location and on a well-served road to/from London.

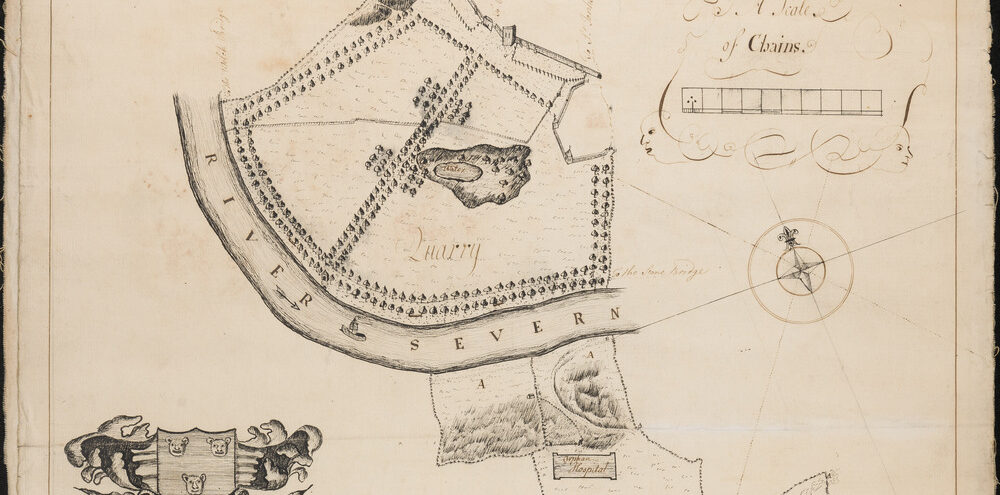

The plan was to build a substantial new hospital in Kingsland, a short way from the town centre. This would be able to accommodate large numbers of children. Work started in 1760 on a three-storey building of 13 bays to a plan drawn by Thomas Pritchard. (Pritchard would later design the world’s first cast iron bridge over what we now know as Ironbridge Gorge.) The building and furniture cost over £15,000; the acquired land cost £1,930. The building was not complete until 1765. In the meantime, two temporary premises were leased in the city to house the Foundlings. The London governors told the Shrewsbury governors and staff to call their institution an ‘Orphan Hospital’ because the word foundling ‘may be used as a name of reproach to the children, as supposing them all illegitimate which [they] certainly are not’.*

The Shrewsbury hospital was initially seen as ‘exceedingly well managed’* under its secretary Thomas Morgan. When the Chester branch hospital was being established in 1762, the governors there were told to take his advice on how it should be set up and operated. Morgan was, however, dismissed in 1765 for several irregularities, not least for poor record-keeping relating to the registration of children under his ultimate care.

The children’s experiences

In total almost 1,200 children were sent to Shrewsbury. Initially they came directly from London or from wet-nurses in Staffordshire to the temporary premises. The Shrewsbury hospital had its own dedicated vehicle (known as a ‘caravan’) for transporting children across the country. Over time, increasing numbers were transferred from wet-nurses in various counties, especially Staffordshire, Derbyshire and Northamptonshire, to dry-nurses in Shropshire. After a year or more the children were then moved from the local nurses to the new-build hospital as its capacity increased. Few children came directly from London in later years.

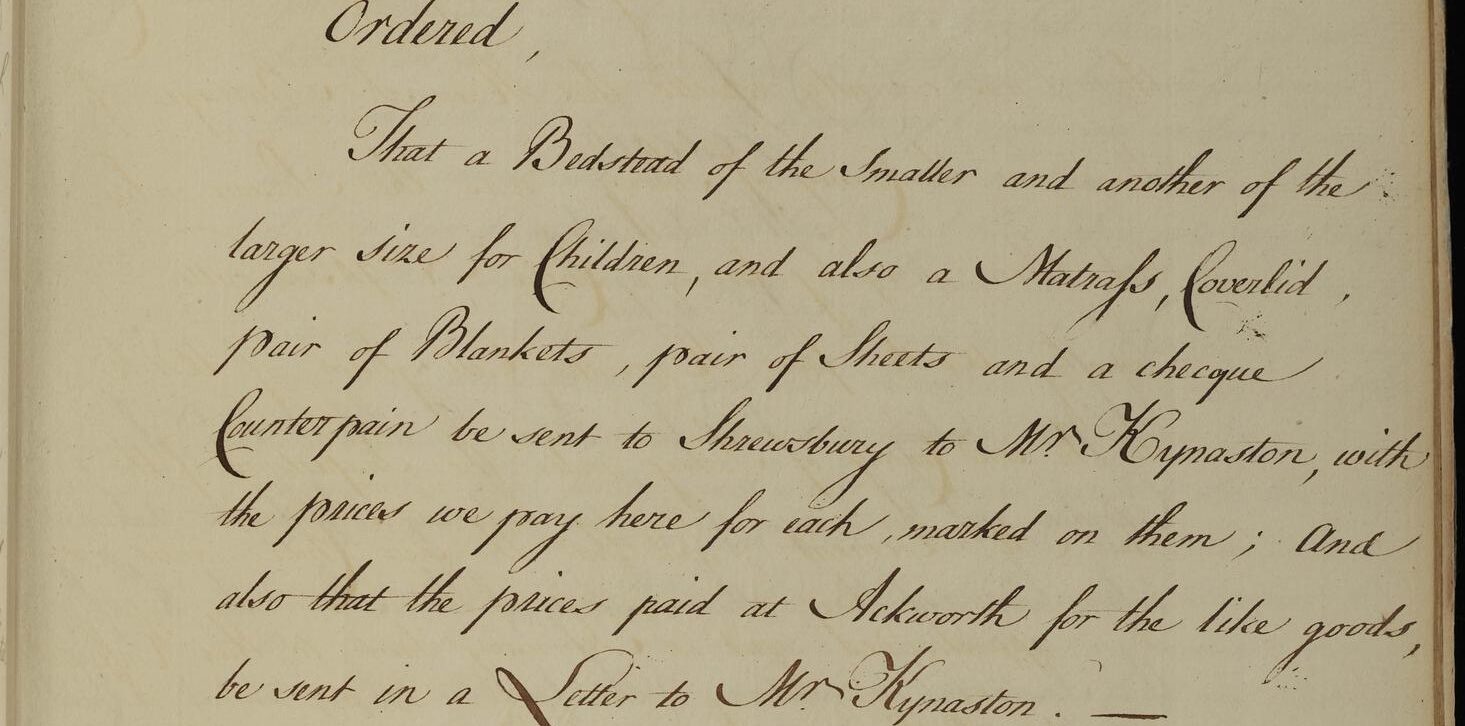

A record survives of the daily routine of the children at Shrewsbury – probably mirrored in the other branch hospitals. They were up at 6 a.m. in the summer (7 a.m. in winter) and, after ablutions and minor chores including emptying their chamber pots, had breakfast. Either side of lunch, the day consisted of schooling for all the children, interspersed with work in the ‘manufactory’ for the older ones. There were various scheduled sessions of play during the day. For boys in particular, play was seen as a way to improve their ‘strength, activity and hardiness’; a master was appointed to ensure they did indeed play. Bedtime was 8 p.m. in winter (9 p.m. in summer). The schoolmaster was paid £12 a year; the school mistress £5 a year.

Much attention was paid to the health of the Foundling Hospital’s children. Shrewsbury had its own infirmary. As well as caring for sick children, the infirmary was used to inoculate children against smallpox, a disease which was often deadly for small children.

Acquiring skills and a work ethic was an important part of the Foundling Hospital experience. For all children these skills included reading and, for the older ones, making textiles in the manufactory. The textile operation was very productive. In its early days girls spun wool but soon started to weave various forms of cloth too. Large quantities of material, as well as finished garments, were sent to London for Foundlings’ clothing. Cloth was also sold commercially to clothiers in various places. Shrewsbury had longstanding connections to the textile industry, particularly wool, and this may have played a part in its selection as a site for a branch hospital.

“Thursday noon a considerable quantity of fine woollen cloth, manufactured by the children belonging to the Foundling-hospital at Shrewsbury, was shewn for sale by the Governors of the Foundling-hospital in Lambs’ Conduit-fields.” – From Liverpool Chronicle, 24 December 1767

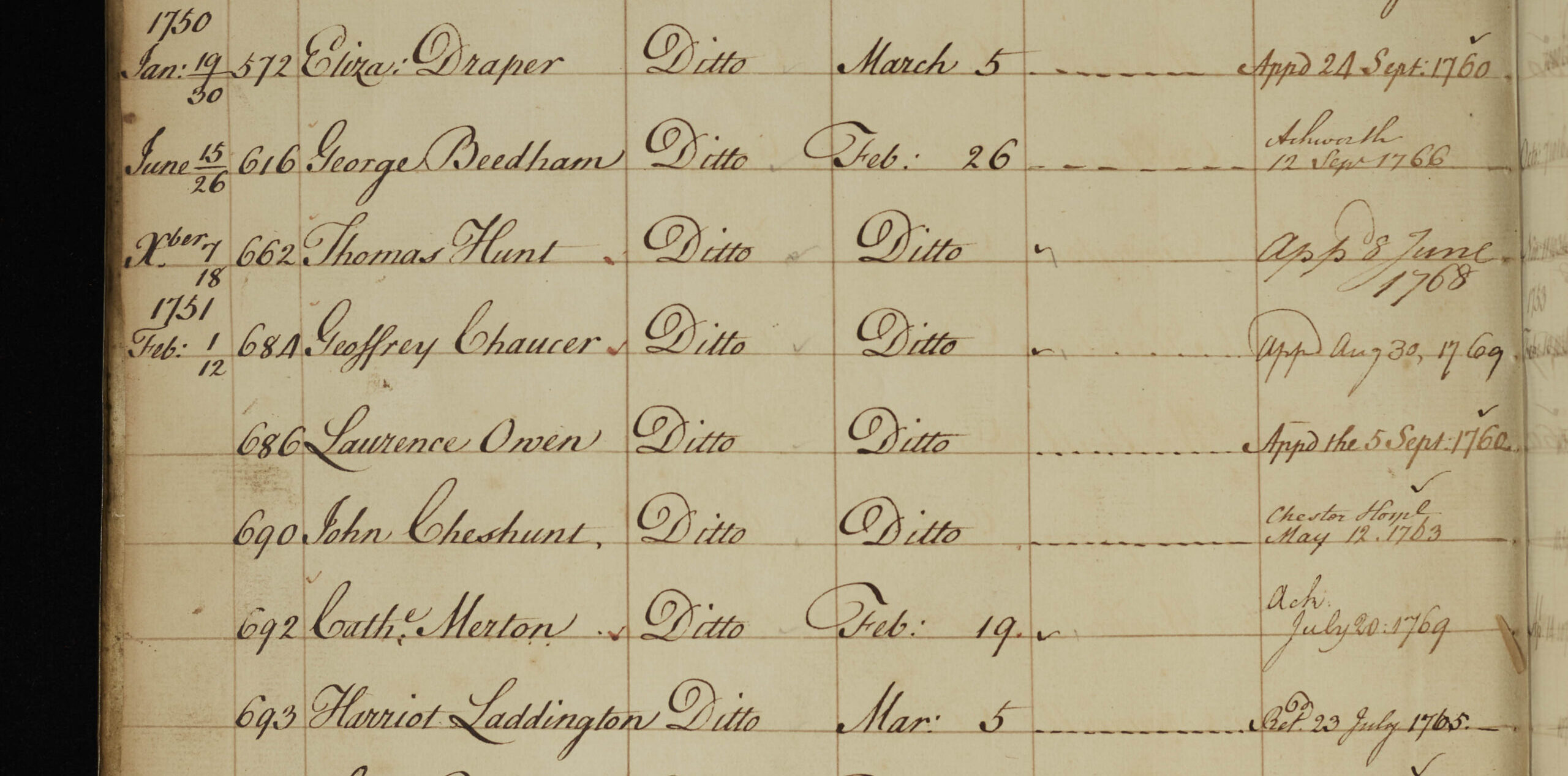

Apprenticeships

Over 400 children were apprenticed directly from Shrewsbury. Most went to masters in Shropshire and nearby counties. The boys’ trades were diverse, with metal industries (e.g. buckle making, locksmithing) and, unsurprisingly, cloth and clothing manufacturing being the most common. The majority of the girls entered domestic service. Harriot Worthy (No. 753) and Jan Cobham (No. 1016), as well as a boy, Leonard Oaks (No. 754), were employed in domestic service for a governor and inspector at the hospital, Roger Kynaston.

While most masters treated their apprentices as the hospital governors would have expected, some did not. In one instance, a master in Walsall, John Livesey, almost killed John Kelly (No. 6517) after tying him to bed – ‘a piece of the boy’s ear came off’. In another terrible case, several girls were subject to serial sexual abuse by their Staffordshire master, Job Wyatt, who beat them if they resisted his advances. The case came to light after two girls, Elizabeth St. John (No. 998) and Elizabeth Short (No. 3171), managed to escape and make it back to the Shrewsbury hospital two days later. It seems Wyatt incurred no punishment although the girls were removed.

The most bizarre case concerning a Shrewsbury child related to the peculiar wants of wealthy Thomas Day. In an experiment, he sought two girl ‘apprentices’ to nurture hoping that one would eventually make him a suitable wife. One of those chosen was Ann Kingston (No. 4579), who was admitted to the hospital in 1766.

Other children seem to have had a happier time, though. Jane East (No. 1400) was apprenticed to a Shrewsbury farmer with, apparently, one of his family acting as witness at her marriage in the same parish 15 years later.

Unusually, in 1763, Grace Walters (No. 4174) was claimed by her mother, Mary Pice, and taken home, aged six, to her birthplace of Norwich. Sir Thomas Challenor made the claim petition on behalf of the mother.

Closure

Like the other branch hospitals, the need for Shrewsbury’s substantial operation declined as the years went by. It was closed in 1772 when the remaining children were transferred to the Ackworth branch hospital or returned to London. One child, Luke Knowler (No. 15096), was sent to Ackworth but later went to London where he worked in the Foundling Hospital for many years. Meanwhile the building at Shrewsbury became, amongst other things, the town’s House of Industry (i.e. a workhouse). Today, it is part of the independent Shrewsbury School.

*Quote from: London letterbook (A/FH/A/006/002/001), 4 November 1762, letter to Trafford Barnston at Chester probably from Taylor White at the London Foundling Hospital.