“I believe every one ought, in duty to do any good they can” Thomas Coram, 1738

Thomas Coram was a campaigner whose greatest achievement, that he called his ‘darling project’, was the Foundling Hospital. But this was just one of many charitable projects he pursued throughout his life.

Early life

Born in 1668 in Lyme Regis in west Dorset, Thomas Coram lost his mother when he was just three years old and was the only child in his family to survive past infancy. His family was not rich or well connected, and he received a basic education, with his early life tied to the shipbuilding industry. In a letter to Benjamin Colman, written on 30 April 1724, Thomas wrote about his background:

“I am no judge in Learning I understand no Lattin nor English neither […] I discended from vertuous good parentage on both sides.”

At 11, his father sent him to sea and later he was apprenticed to a shipwright before going to Boston in America in 1694 to establish a new shipyard. For the next 10 years, Coram lived in New England. As a staunch Anglican, he ran into trouble with his Puritan neighbours and there was even an attempt on his life. To find out more about his time in America, click here.

Coram’s campaign begins

When he returned to England with his American wife, Eunice, he was shocked to discover destitute and dying children on London’s streets. He decided to petition the king for a charter to create a foundling hospital supported by subscriptions to protect these children. But at first he found it impossible to gain the backing of anyone influential enough, and there was opposition to the idea. This was due of social attitudes to illegitimacy and fear that providing for the babies of unmarried mother would encourage immorality, as well as a general attitude that it was not helpful to support ‘improvident’ parents unable to care for their children.

His lack of social graces, which offended some of the influential upper class, didn’t help. He once complained in a letter that he might as well have asked them to “putt down their breeches and present their backsides to the King and Queen”.

Undaunted, and inspired by the role of French women in caring for foundlings in Paris, Thomas Coram decided to ask English noblewomen (known as the ’21 Ladies of Quality and Distinction’) to lend weight to his petition and gain the interest of influential men along the way. Ten years later, King George II signed the Foundling Hospital charter. In a letter to Selina, Countess of Huntingdon, 1739, who was among those who signed Thomas Coram’s Ladies Petition to King George II, he wrote:

“After seventeen years and a half ’s contrivance, labour and fatigue I have obtained a charter for establishing a hospital for […] deserted young children.”

The first meeting of the governors of the Foundling Hospital took place at Somerset House. Thomas Coram, by then aged 70, made a moving speech to the Duke of Bedford, the Hospital’s new President:

“My Lord, Duke of Bedford,

It is with inexpressible pleasure I now present your grace, at the head of this noble and honourable corporation, with his Majesty’s royal charter, for establishing an Hospital for exposed children, free of all expense, through the assistance of some compassionate great ladies and other good persons.

I can, my lord, sincerely aver, that nothing would have induced me to embark in a design so full of difficulties and discouragements, but a zeal for the service of his Majesty, in preserving the lives of great numbers of his innocent subjects.

The long and melancholy experience of this nation has too demonstrably shewn, with what barbarity tender infants have been exposed and destroyed for want of proper means of preventing the disgrace, and succouring the necessities of their parents.

The charter will disclose the extensive nature and end of this Charity, in much stronger terms than I can possibly pretend to describe them, so that I have only to thank your Grace and many other noble personages, for all that favourable protection which hath given life and sprit to my endeavours.”*

On the evening of March 25, 1741, at a temporary site, the Foundling Hospital opened its doors.

Thomas Coram the campaigner

We don’t know whether there was a particular incident that aroused his compassion, or whether it was because of his staunch Anglican faith, or because he had experienced a difficult childhood himself after his own mother died when he was only three or four.

What we do know is that Thomas Coram was a determined campaigner and that he could not and would not ignore destitute children on London’s streets.

Thomas Coram was also a passionate advocate for girls’ education until late in life. During his time in America, he produced a scheme that promoted the education of native American girls in the American colonies.

Coram also supported the growth of British trade and was heavily involved with both the campaigns for the Tar Act of 1704 and the Hat Act of 1732. These served to expand and protect trade across the Atlantic. Tricorn hats were later provided to him free for life by The Hatters’ Company in tribute to his work in trade. This knowledge and experience inspired Coram to use the model of a trade association for his charity, with a board of governors holding a mission in trust.

Coram’s later life

Unlike most of his fellow governors, Coram was neither wealthy nor an aristocrat. He did not hold back from expressing his views and his plain-speaking left him an outsider. This led in 1743, to him being de-selected from the General Committee of the Foundling Hospital and no longer able to be involved with his ‘darling project’. Widowed and childless, he faced a lonely old age and was to be seen wearing his distinctive red coat, handing gingerbread to children through the railings, which still bound the site where Coram is based today. He also attended christenings in the chapel and was godfather to more than 20 children at the Foundling Hospital.

Even in his seventies, Coram was not one to sit idly by. He campaigned unsuccessfully for a second Hospital, knowing that there were more children to be cared for.

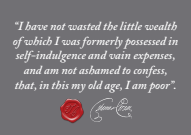

However, as he reached his eighties some of the governors began to realise he had fallen on hard times. When his friend Samson Gideon heard Coram was in financial difficulty, he organised a pension to be raised, to which the Prince of Wales contributed. With it, Coram rented rooms near Leicester Fields, close by. He received the freedom of the borough in 1749 from the mayor and corporation of Lyme.

Thomas Coram’s legacy

Thomas Coram died on 29 March 1751, aged 84. The governors organised a funeral at the Hospital chapel to recognise his many achievements with the choirs of Westminster Abbey and St Paul’s Cathedral in attendance.

He was buried according to his wishes on the site of the Foundling Hospital. He now rests in St Andrew’s Church, Holborn, alongside the font and pulpit from the original Hospital chapel.

The inscription on his commemoration stone, which now stands in Ashlyns School (formerly the Foundling Hospital School in Berkhamsted) begins: “Captain Thomas Coram, Whose Name will never want a Monument, So long as this Hospital shall subsist.”

Thomas Coram’s life and ‘darling project’ has inspired generations of writers, playrights and novelists. The legacy he left behind continues. Today we are known as the Coram Group of charities, named after the man whose single minded determination created a charity that now helps more than a million children and young people every year.