In an exceptional time known as the General Reception (1756-1760), the Foundling Hospital admitted almost 15,000 infants. To care for this huge number of children, branch hospitals were needed. Westerham was the fourth branch hospital to be opened.

Beginnings

Not only was Westerham, Kent, a remarkably healthy parish, but it was barely 20 miles from London, making communication easy and supplies economical. Importantly, it was already an area where individual Foundlings were being cared for by wet nurses. These women were paid by the Foundling Hospital to take infant Foundlings into their cottages and bring them up until they were between five and seven years old. Then the children would be returned to the Foundling Hospital for their education.

Thomas Ellison, a governor of the Foundling Hospital, owned a house in Westerham town called Spiers, known today as Quebec House. Ellison also owned a house named Wellstreet two miles outside town. It is now Chartwell, the former home of Sir Winston Churchill.

When it was decided in 1759 to open a branch hospital in Westerham, Ellison offered a lease on Wellstreet. The house had farmland, barns, cottages, and outhouses. It was renamed the Westerham Branch Foundling Hospital and operated from July 1760 to November 1769.

The Hospital was run by a Secretary or Master and by a Matron. Over the nine years, the Hospital employed a total of 90 people to run the house and look after the children.

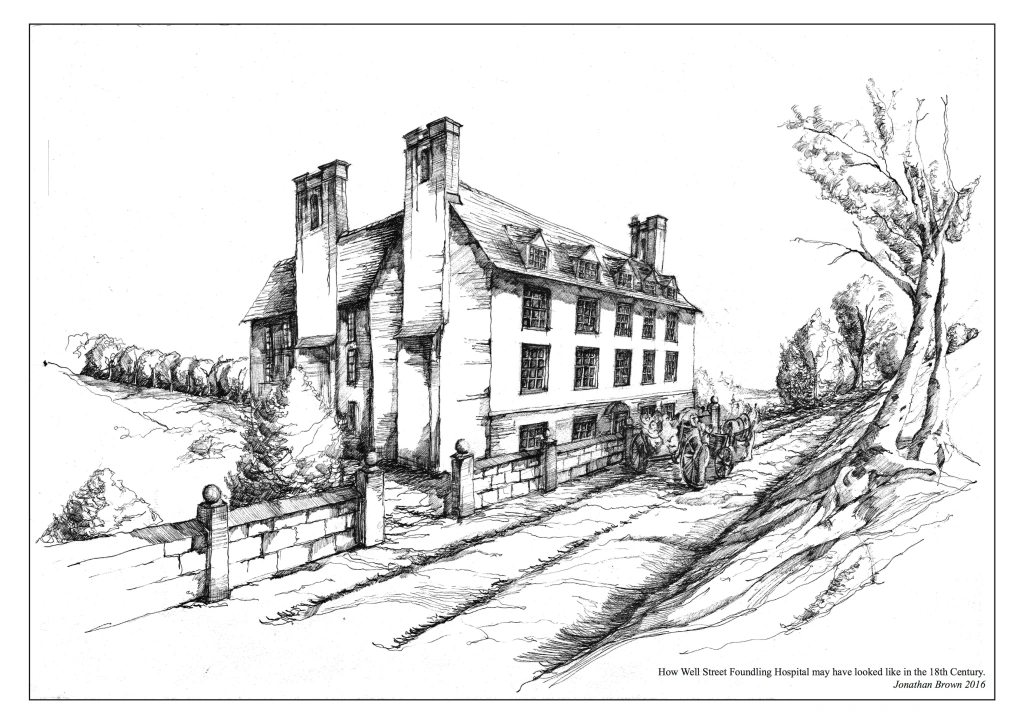

How the Westerham branch hospital might have looked c.1760. Drawing by Jonathan Brown (2016) commissioned by Alethea R. Mitchell

Daily life

In total, 469 children went through the doors of Wellstreet, with a maximum of 235 Foundlings accommodated at any one time. The children’s day was regulated, and boys and girls were segregated for lessons, eating, working, and play.

The children had lessons using alphabets and spelling books, as well as prayer books. They could read and spell, if not write well. Although records show no inventories of children’s toys (e.g., hoops and balls), the children must have brought with them local knowledge of games played in their foster-homes and villages.

They had regular meals. The Wellstreet farm had 160 acres of land, a hop garden and orchards. We know from household accounts that pigs and cows were kept and that bacon was cured and sold locally. The local butcher, Mr Killick, supplied beef and mutton in considerable quantities. A local baker, James Burnett, had the contract to make the bread.

Barrels of rice were ordered from the London Hospital for ‘puddings for the children’. Spanish liquorice and cheesecakes were bought for sick children. Chicken was ‘for a Medicine’, as was brandy and red port wine (used to mix with the medicinal ‘barks’ and ‘tinctures’). Fish was rarely bought, except salt fish for Good Friday and Ash Wednesday. For Michaelmas: goose.

According to the household accounts, the house had been partitioned into dormitories or ‘wards’. The children slept three to a bed – no doubt unwittingly contributing to the spread of illnesses. Matron Ann Wadham’s letters tell us something of the diseases and illnesses the children contracted. Measles was the most dangerous, with outbreaks of dysentery and ‘The Itch’ (scabies) prevalent. From her letters, we also learn of the medications and treatments she used, and can see how hard she tried to relieve the children’s distress and comfort them.

The children attended ‘Divine Service’ at St Mary’s Parish Church, Westerham. They had their own benches, possibly for two reasons: One, to keep the children segregated, and the other to put them on show, so that the public could see that they were well cared for and well behaved. These were ‘Parliamentary’ children, and it was tax-payer’s money keeping them. It was important to the governors to demonstrate to local people of influence that the money was being effectively spent.

Foundlings at work

All the children were taught to mend their own clothes. Boys and girls knitted stockings and mittens. The girls made shifts, shirts, aprons and the day and night caps that were worn. A tailor made the boys’ suits and the girls’ coats; clothes were frequently re-lined. A local chandler supplied leather breeches for the boys, when they were old enough to work in the fields. (The matron ordered a bell so that the boys could be called in from the fields for the meal times.)

In the workshops the children spun flax, with the flax thread sent up to London for sale. At one time there were as many as 36 ‘double threaded’ spinning wheels in the workshops. It was always important to the governors that children learned to ‘acquire the habit of industry’. This encouraged them to be conscientious workers and therefore desirable as obedient apprentices.

When the children reached the age of 11, they were apprenticed out to Masters. Westerham succeeded in apprenticing only 18 children directly. All the other children went back to the London Foundling Hospital, from where they were apprenticed. Among these were Edmund Fitz-George, Eleanor Weathers and John Crowdhill.

Westerham’s low apprenticeship record could have been for a number of factors: the proximity to London, with its ready demand for apprentices in workshops and manufacturing, and the lack of manufacturing in the Westerham area. It was a healthy parish, with a low mortality rate, meaning there was no shortage of young workers for what was mostly a rural economy.

Closure

The Westerham branch hospital closed quite suddenly in 1769. During October and November, the children, 20 or 30 at a time, left by waggon, out through Westerham and on to the London Foundling Hospital. Many were subsequently transferred to the Ackworth branch hospital in Yorkshire.

For more information about this branch hospital, go to the Westerham Foundling Hospital website.

Find out more about other Branch Foundling Hospitals

Copyright © Alethea R. Mitchell