Stories of Interest volunteer, Xinyi Xie, explores the intertwining stories of Eleanor (Ellen) Weathers and George Grafton, who found love at the Foundling Hospital. Eleanor was gifted at tambour embroidery and you can find out more about her experiences below.

The Stories of Interest volunteers have been researching the little-known themes and connections between pupils at the Foundling Hospital to tell new and fascinating stories.

In 1812, Eleanor Grafton died aged 62, after spending most of her life living and working in the Foundling Hospital. We usually imagine a children’s home as a ruthless and heartless place, where helpless children have been abandoned by their families. But for Eleanor, the Foundling Hospital was a refuge in difficult times.

Early years and apprenticeships

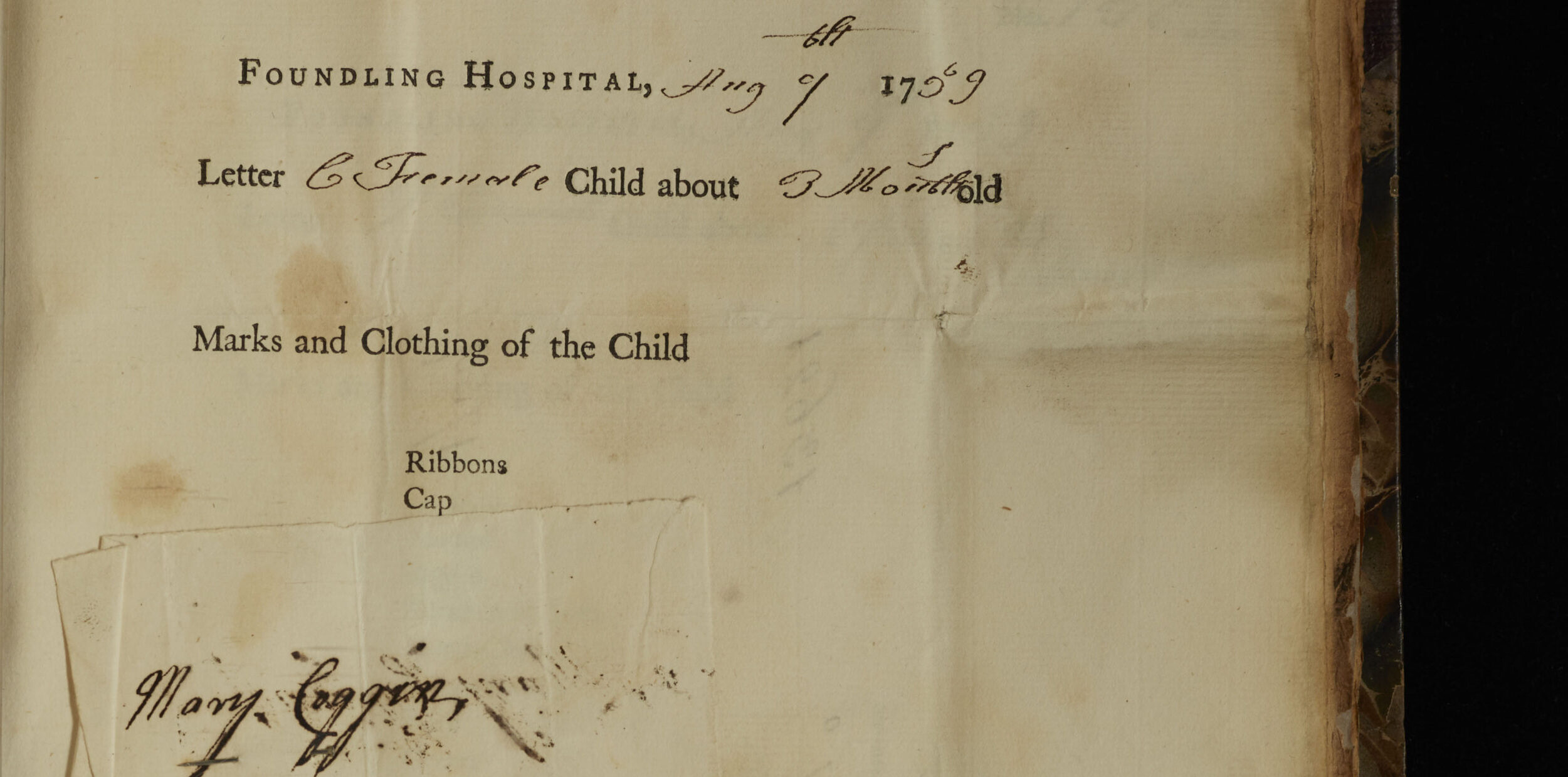

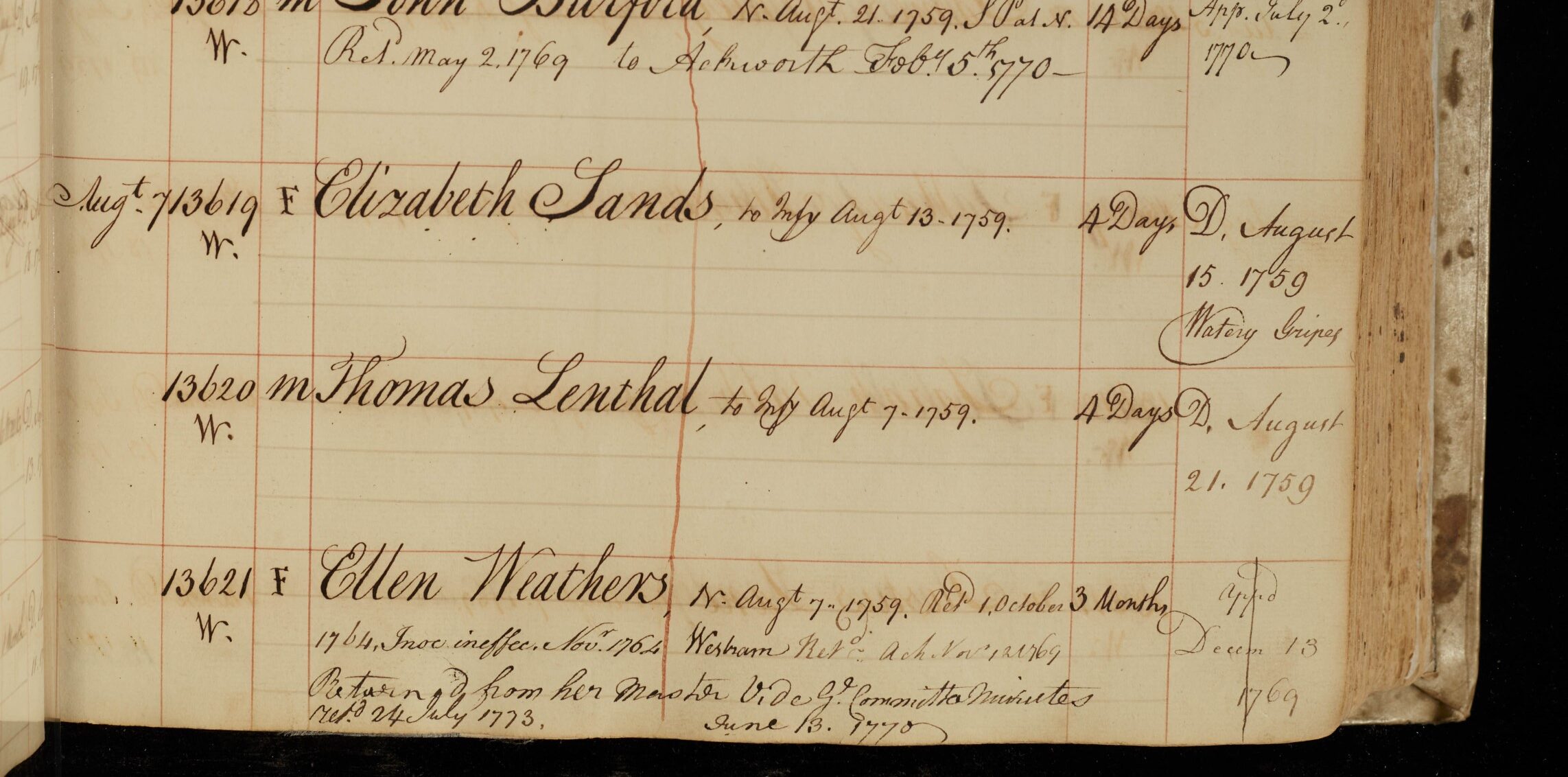

On 7 August 1759, she entered the Hospital as a three-month-old infant named Mary Coggin. She was renamed Ellen Weathers (no. 13621) and later known as Eleanor. Then, she was immediately sent to a wet nurse in Kent and at the age of five or six entered the Westerham Hospital branch in Kent.

In December 1769, the Foundling Hospital arranged an apprenticeship for Eleanor, aged 10. She was sent to Philip Hardcastle, a blacksmith in Pannal, Yorkshire, to learn to be a domestic servant. She was supposed to spend 11 years in this apprenticeship, but she was ‘returned by her master’ in July 1773. The archival records do not state the reason why.

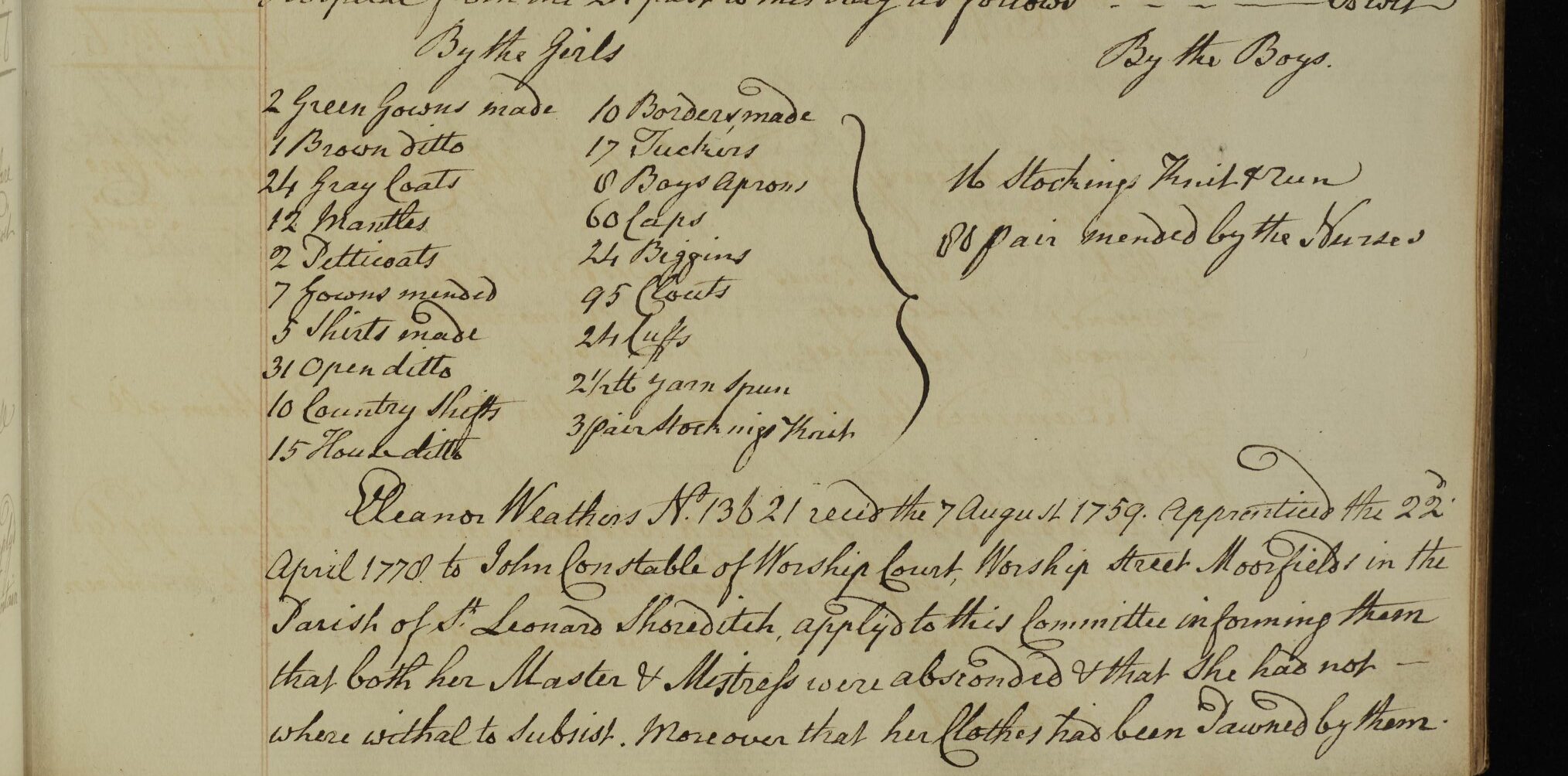

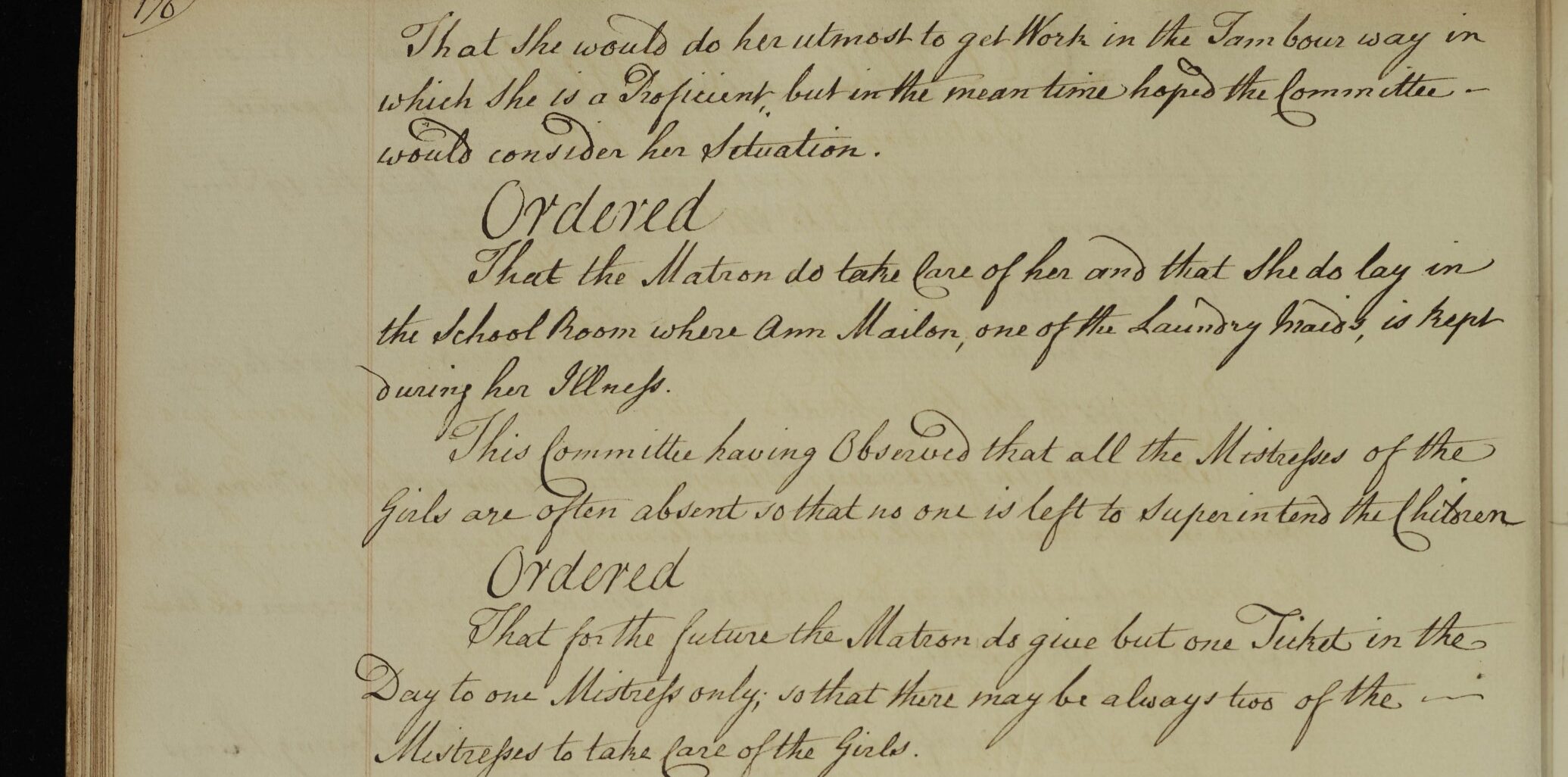

Then, in April 1778, Eleanor started an apprenticeship with John Constable in Shoreditch, London, where she learned to do tambour embroidery, working on fabric stretched tightly over a frame. Her apprenticeship was to last until August 1780, but again Eleanor met with trouble. In 1779, her master and mistress experienced ‘distressing’ economic circumstances. They ran away, abandoning Eleanor and pawning all her clothes. She was unable to support herself and appealed to the Hospital for help. The Hospital decided to let Eleanor stay in the schoolroom until she could find a job. Not long after, she became a ‘yearly servant’ for Mr Smith, whose wife took in tambour work in New Street, Whitechapel, London.

Connections with other Foundlings

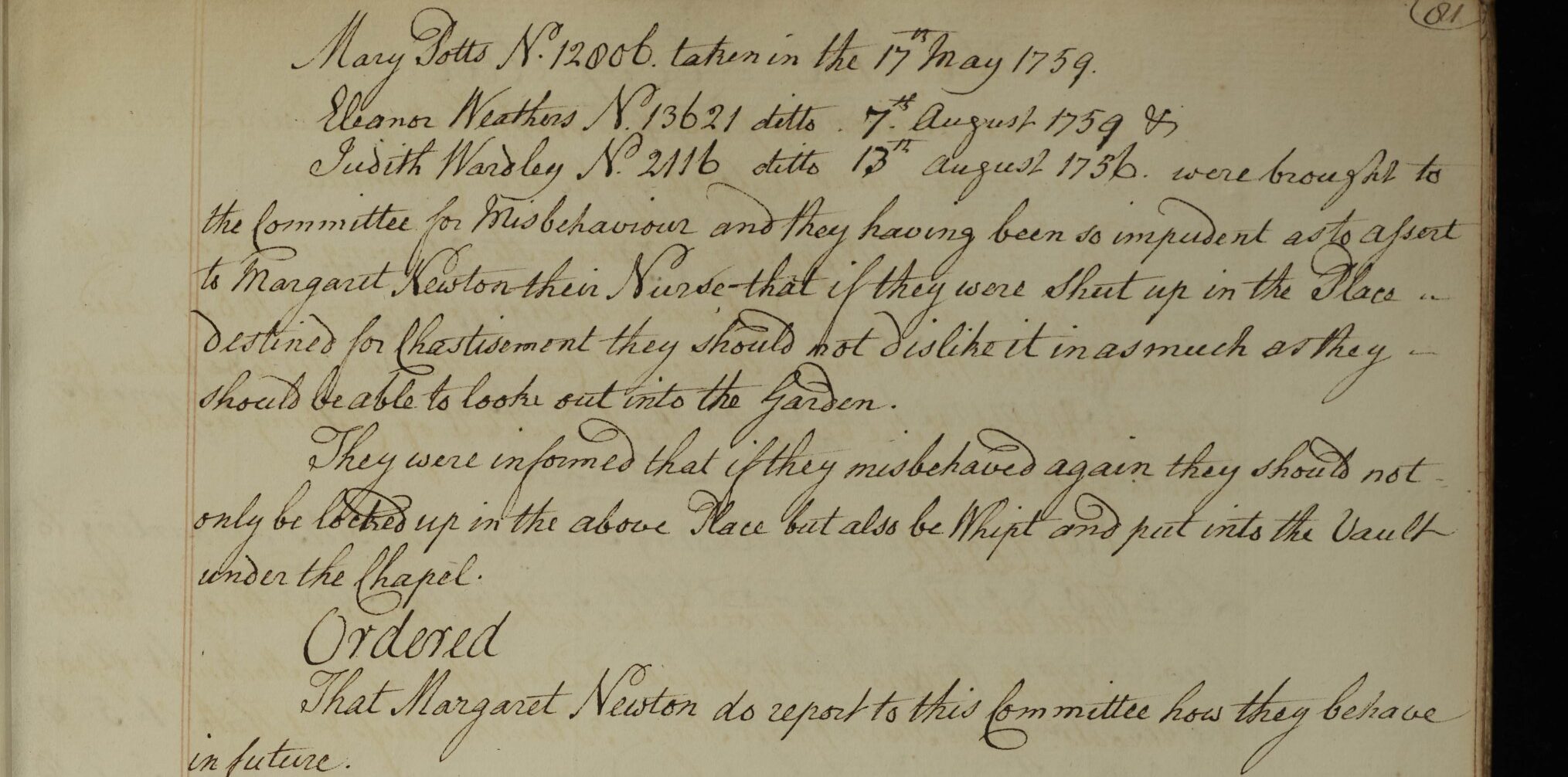

Eleanor’s life at the Hospital interconnects with that of two other female Foundlings. In 1777, she was brought up in front of the Hospital Sub-committee and warned about misbehaviour along with Mary Potts (no. 12806, admitted 1759) and Judith Wardley (no. 2116, admitted 1756). Earlier, the three girls had told the Hospital nurse that ‘if they were Shut up in the Place destined for Chastisement they should not dislike it in as much as they should be able to look out into the Garden’. Because of their impudence, the committee ordered that if they misbehaved again, the girls should be whipped and ‘put in the Vault under the Chapel’ rather than the room with the view of the garden.

Mary, who was lame, did tambour embroidery in her apprenticeship, just like Eleanor. Mary also had a run-away master, in July 1779. But she soon got a job elsewhere and left the Hospital forever in January 1780. When Eleanor retuned to the Hospital in 1779, Judith was working as a washerwoman in the laundry there. The Sub-committee minutes also record that Judith helped the nurses with inoculation of the younger children. Judith left the Hospital around 1785. When the three girls were staying at the Hospital, did they develop close friendships because of their similar experiences?

Health issues

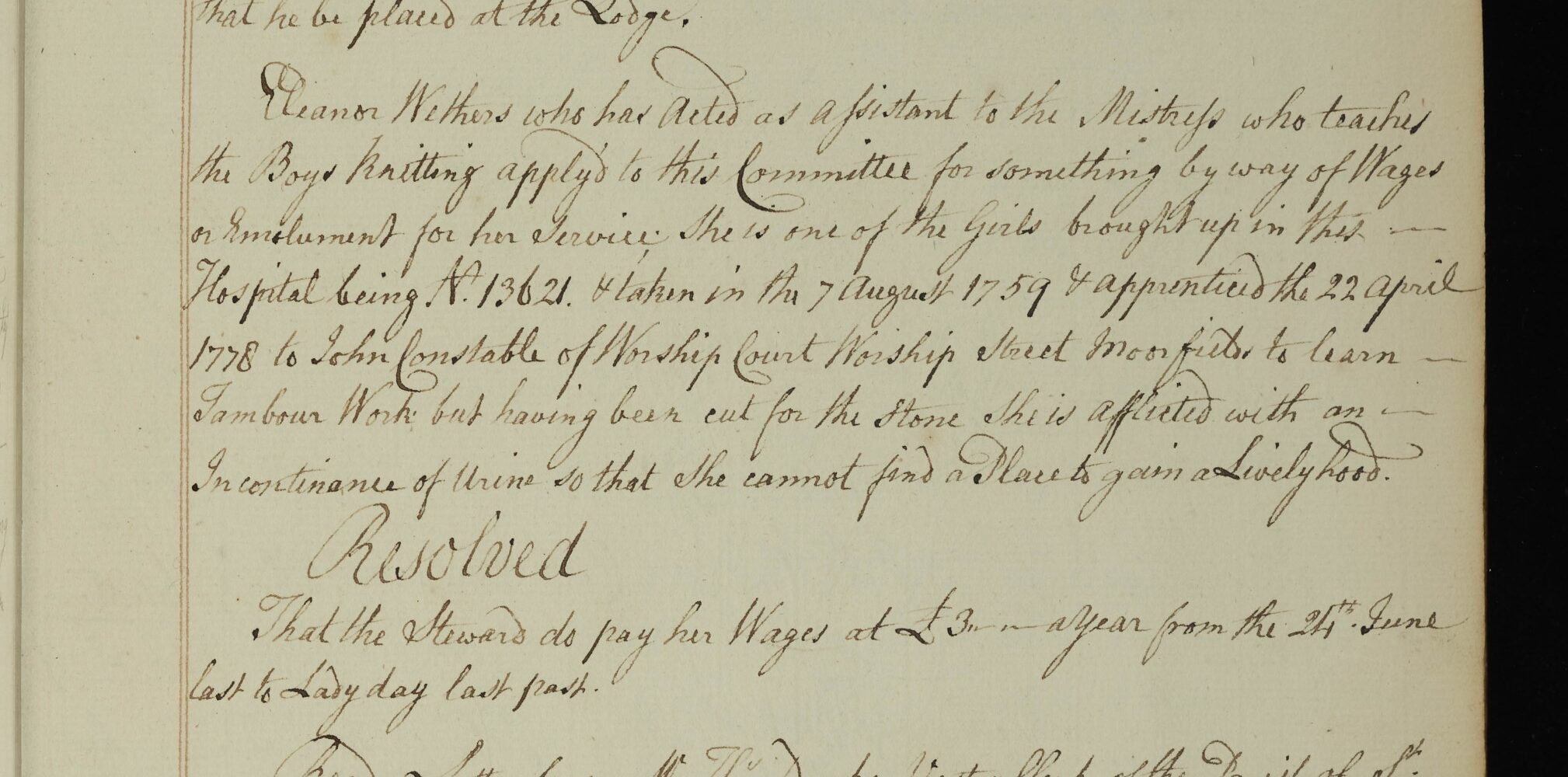

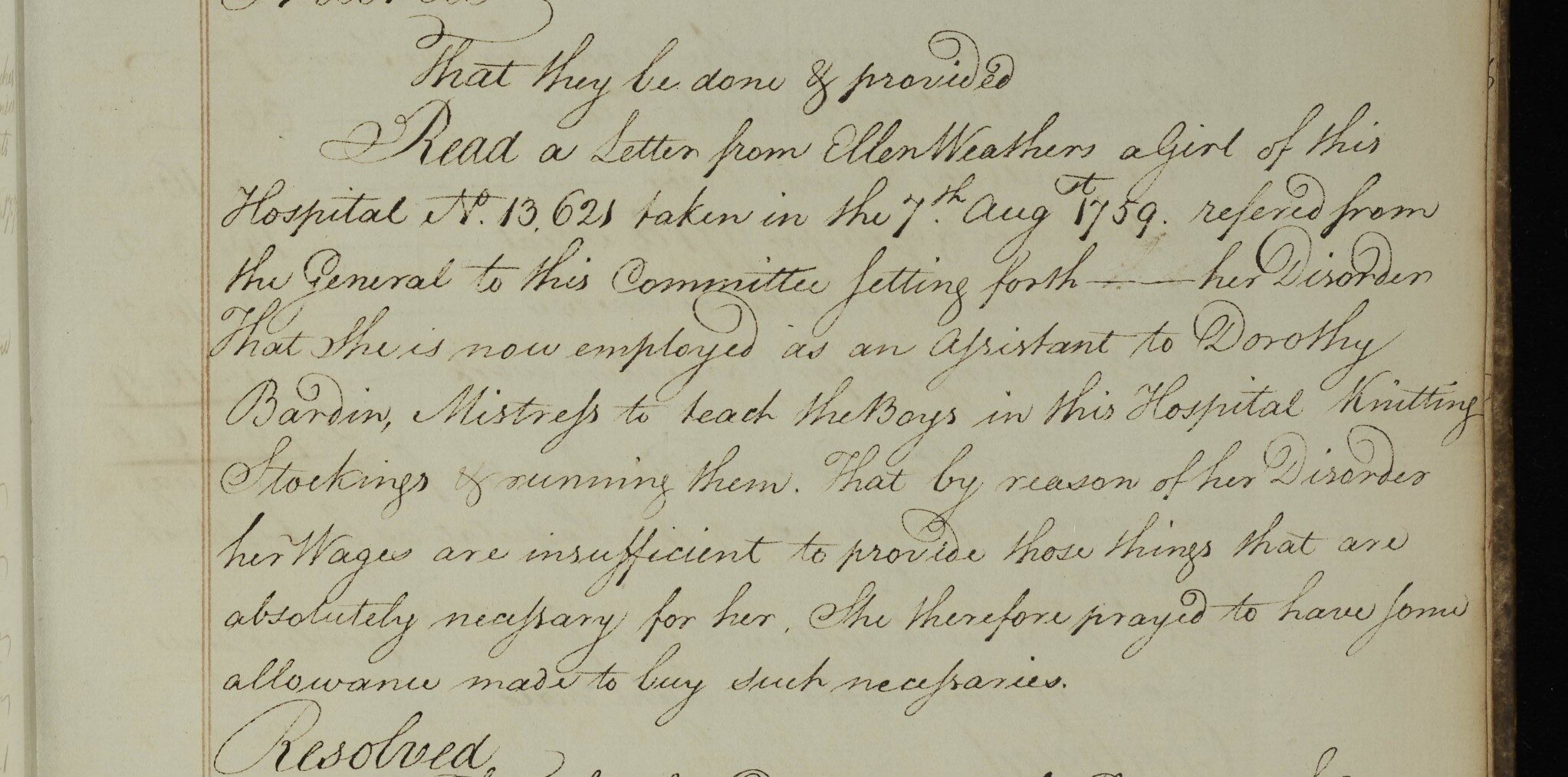

At some point in the early 1780s, Eleanor developed urinary incontinence after passing a kidney stone, and it became difficult for her to find employment. Therefore, the Hospital gave her work as an assistant teacher in the boys’ knitting school, where they learned to knit stockings. As her incontinence caused extra expense, in 1787, she asked for financial assistance from the Hospital. The Sub-committee granted her a wage of £3 a year for her teaching position.

While working at the Hospital, Eleanor met her husband, George Grafton, a Foundling admitted in 1770 (no. 16644). The two had much in common. Similar to Eleanor, George stayed in the Foundling Hospital for most of his life because of his clubfoot, a condition in which a foot is turned in and under. Clubfoot mostly happens to boys and could have been cured at an early age, but it was not diagnosed until he was eight years old. Because of her disability, Eleanor might have understood George’s situation better than others.

Work and marriage

Another similarity between them is their proficient work. When Eleanor was allowed to return to the Hospital, her ‘proficient’ tambour work was mentioned in the Sub-committee minutes. George did not go out to do an apprenticeship because of his clubfoot, but in 1784, when he was 14 years old, records say he was ‘ingenious’ in mending clothes. Under his direction, other boys had mended a total of 73 coats and 185 pairs of breeches. In 1787, George asked to move from the boys’ ward to the adult servants’ rooms and requested new clothes; these requests were granted. In 1788, George was apprenticed to a shoemaker.

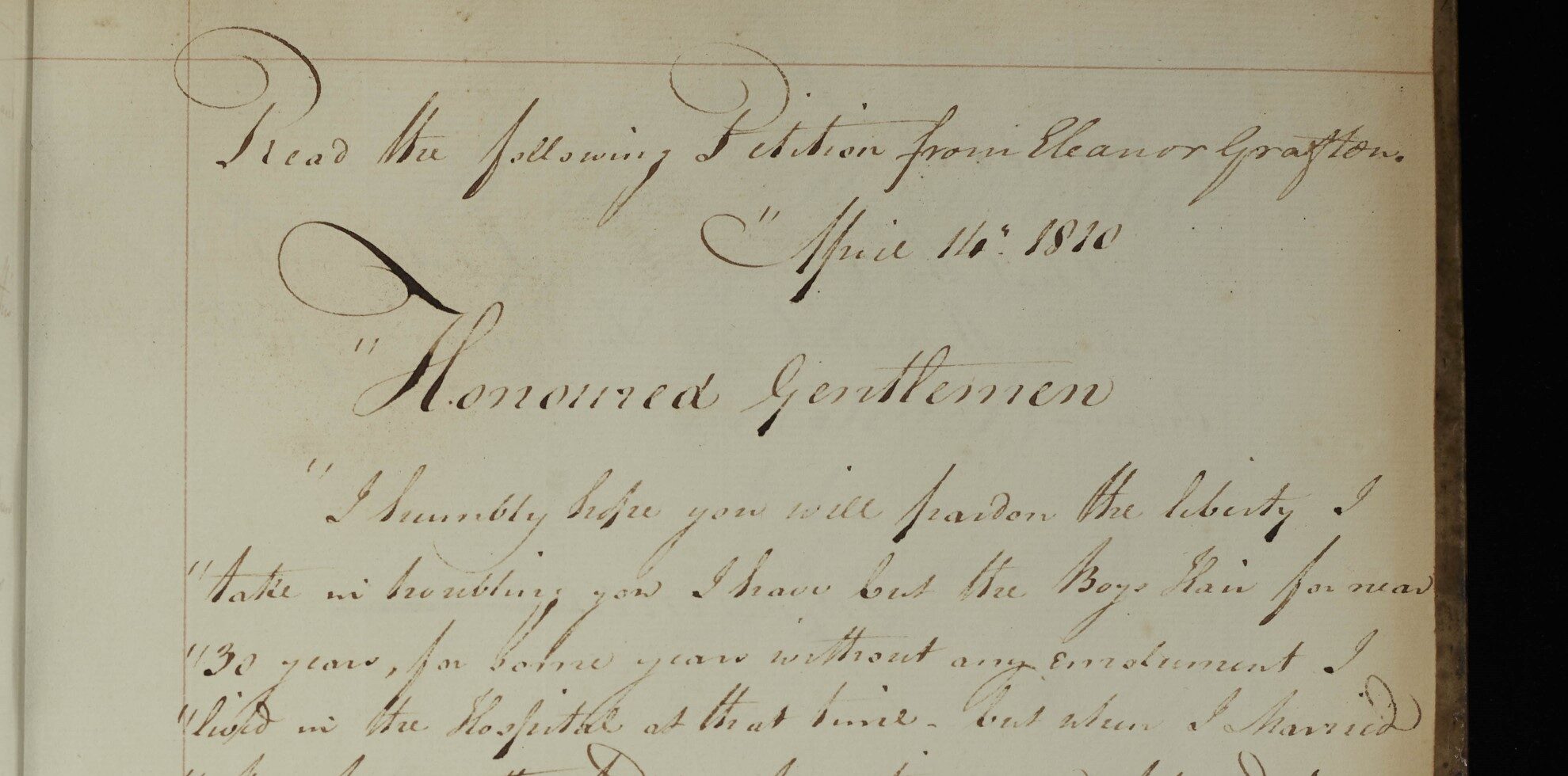

In 1792, George and Eleanor were married in St. Pancras Parish Chapel and left the Hospital to set up their own home. They had four children, two of whom survived into adulthood. Eleanor continued to work at the Hospital, cutting the foundling boys’ hair for a penny a head. With George’s death in 1807, Eleanor was alone. In 1810, she wrote to the Sub-Committee, ‘I owe 24 shillings for rent and know not what to do without some humane and compassionate friend’. The Committee granted her a salary of four guineas a year for her work. Despite difficult experiences during her life, Eleanor did find compassion, friendship and love at the Foundling Hospital.

Read more about Eleanor and George’s story and see George’s archival records in this article.

Eleanor’s archival records

Bibliography

Coram’s Foundling Hospital Archive

Eleanor Weathers

Billet: A/FH/A/09/001/151/091

General Register: A/FH/A/09/002/004/091

Nursery Book: A/FH/A/10/003/006/242

Inspections Book: A/FH/A/10/004/002/427

Westerham Register: A/FH/A/10/008/001/029

Apprenticeship Register: A/FH/A/12/003/001/358

Sub-Committee Minutes:

A/FH/A/03/005/013/085

A/FH/A/03/005/014/205-206, 217-218

A/FH/A/03/005/016/094-95

A/FH/A/03/005/017/033

A/FH/A/03/005/019/207-208, 243

A/FH/A/03/005/028/161

George Grafton

Billet: A/FH/A/09/001/180/231

General Register: A/FH/A/09/002/004/394

Apprenticeship Register: A/FH/A/12/003/002/198

Sub-Committee Minutes:

A/FH/A/03/005/014/034, 074

A/FH/A/03/005/016/133-134

A/FH/A/03/005/017/188, 233

A/FH/A/03/005/018/031-032

A/FH/A/03/005/019/129, 141-142, 207-208, 229, 245

A/FH/A/03/005/022/175

Mary Potts

General Register: A/FH/A/09/002/004/010

Sub-Committee Minutes: A/FH/A/03/005/009/088-90; A/FH/A/03/005/015/042-43, 63

Judith Wardley

General Register: A/FH/A/09/002/001/219

Sub-Committee Minutes: A/FH/A/03/005/015/035; A/FH/A/03/005/016/094-95

Copyright © Coram. Coram licenses the text of this article under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 (CC BY-NC).