At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Foundling Hospital was landlord to those who campaigned for women’s rights. On International Women’s Day 2022, Coram historian Carol Harris highlights some of the pioneering women who lived and worked in and around the estate.

The 56 acres of the Foundling Hospital Estate covered a substantial part of Bloomsbury. It included two squares — Mecklenburgh and Brunswick — which were adjacent to the Foundling Hospital itself, as well as the adjoining streets. The estate provided the charity with a regular income, from the late 1790s until it was sold in 1926.

Many of the houses were divided into flats, or let as single rooms and as offices. For the tenants, the area provided affordable accommodation near the centre of London. One of the most famous residents was the Suffragette Emily Davison, who lived at 31 Coram Street.

Emily Wilding Davison— Public Domain via Wikipedia

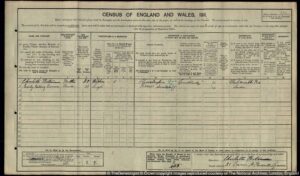

On 2nd April 1911, women campaigning for the vote refused to add their names to the National Census. Emily marked the occasion by hiding in a broom cupboard in the Palace of Westminster. She was discovered and arrested but not charged. The Clerk of Works at the House of Commons included her name in the returns for that address. However, she was included twice in the census, as her landlady, Charlotte Bateman, also put her name on the return for the Coram Street flat. Emily Davison’s occupation is listed as a ‘Political Organiser’, a post she held with the Women’s Social and Political Union (its members were known as the Suffragettes) until her death in 1913, from injuries she received after protesting at the Epsom Derby.

VtsForWmn Emily Davison 31 Coram Street 1911 Census — © The Genealogist

In 1913, another leader with the WSPU, Annie Kenney, was living in flat at 19, Mecklenburgh Square, with her sister and fellow Suffragette Jessie, and the leading Welsh Suffragette Rachel Barrett.

Annie Kenney, 1909 — Bain News Service, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Suffragettes had become increasingly militant: their tactics involved arson and bombings, to damage property of those who opposed them. Their targets included churches, golf clubhouses, railway carriages and MP’s homes. On 30th April 1913, police raided the flat at no. 19 and took away papers on this campaign, including a leaflet on how to make bombs.

Across the square, no. 34 was the location of Reform House. This was the address for several radical organisations involving Suffragist women. The Suffragists were members of various organisations, many of them grouped under the banner of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. Like the WSPU, Suffragists were prepared to break the law, but their tactics were based on non-violent civil disobedience.

One of the best-known was Margaret Llewellyn Davies, who ran the People’s Suffrage Federation from Reform House. This organisation campaigned for equal voting rights for all men and women. Among the federation’s volunteers was the author Virginia Woolf, whose various homes in Bloomsbury included addresses in Mecklenburgh and Brunswick Squares. She did clerical work for the federation and wrote to a friend of ‘the office with its ardent but educated young women, and brotherly clerks.’

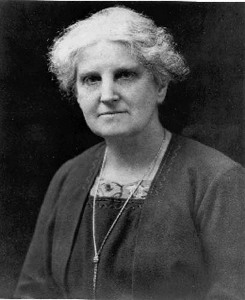

Margaret Llewellyn Davis – Wikipedia

In the same building, another Suffragist, Mary Macarthur, ran the Women’s Trade Union League, the National Federation of Women Workers and, with her colleague Gertrude Treadwell, founded the Anti-Sweating League. They campaigned for better pay and conditions for those working in ‘sweated labour’, so-called because they worked long hours for very low pay. Conditions were worst in lacemaking, boxmaking, chain-making and clothing trades – where almost all the employees were women – and the campaigns resulted in the first minimum wage in the UK. During World War One, Macarthur became secretary of the Government’s committee advising on the employment of women but died of cancer at an early age.

Mary Macarthur – Wikimedia Commons

Helena Normanton lived at no. 22 from 1919 to 1929. She qualified as a lawyer despite strong resistance from within the legal profession. The law was on their side until the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919, which opened up the legal profession to women. Even so, she still faced opposition as she tried to put the law into practice.

Normanton supplemented her income by writing magazine columns giving legal advice on topics such as property, marriage and divorce, and by renting out rooms in no. 22. She was the first woman to have a passport in her unmarried name, the first woman to join the Inns of Court (1919), the second to practise at the bar (1922), and the first woman to appear in the High Court and at the Old Bailey, and to lead a prosecution in a murder trial.

Helena Normanton — LSE Library, Wikimedia Commons

Medicine was another male-dominated profession which fought hard to stop women qualifying and practising. It is not surprising then that many of the women doctors living on the Foundling Hospital Estate were also active in campaigns for women’s rights.

Dr Elizabeth Knight was a wealthy and radical campaigner in the Women’s Freedom League, another suffragist organisation. In 1920, she funded the Minerva residential club for women established by the WFL at 28a Brunswick Square. Like many women who were doctors, she was also active in the Women’s Tax Resistance League – its members were suffrage campaigners who refused to pay tax because they had no right to vote.

The first medical school to train women in England is in Hunter Street, just by the site of Minerva Club. It was founded in 1874 by pioneering doctors Sophie Jex-Blake, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Emily Blackwell and Elizabeth Blackwell.

London School of Medicine for Women – Wikimedia Commons

You can find out more about these and other women who led the fight for the vote on two history walks – Women and the Vote, and Militant Medics. Email Carol Harris at harbro@btinternet.com for details and to book your place.

Copyright © Coram. Coram licenses the text of this article under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 (CC BY-NC).