Ruth Miller attended the Foundling Hospital from the 1940s and is and a member of the Old Coram Association, a group bringing together former pupils.

Beginnings

Ruth was born in 1937 and came to the Foundling Hospital in Berkhamsted, aged five, in 1942. She had lived with her foster family in Essex up until that point.

Ruth vividly remembers the day she came to the Hospital: “That day is imprinted on my mind, I have such clear memories. I remember my teacher had said to me ‘you’re a clever girl so you’re going to go to a big school’. That day I got on a coach with my foster mother and we made the journey to Berkhamsted, which felt like a very long way.

“I asked my foster mother if I would be able to come home for dinner, which in those days was midday. She said no but didn’t say anything more. Then as we drove up to the big iron gates, I asked if I would be coming home that day. We got off the coach and all she said was ‘be a good girl’ and she kissed me goodbye. It was several years before I saw her again.”

Routine at the Hospital

Ruth describes life at the Hospital as very regimented: “We marched everywhere, walking two by two. I remember the buttons on our uniform and the aprons we wore were very difficult to do up, so we lined up in a row and did up the buttons of the girl in front of us, and the nurse would do the buttons for the girl at the back of the row.

“We started the day washing our faces and cleaning our teeth and the nurse would instruct us – ‘taps on, brushes under, toothpaste, brush, rinse…’ and so on. Then we would march to the dining room, wait for the gavel to bang for us to sit down, and then the gavel would bang again, signalling that we could eat. We ate in silence and had to eat everything on our plates.”

Education and sport

Describing her education at the Hospital, Ruth says: “Maths was my least favourite part. I was terrified of our teacher and would shrink down behind the girl in front and hope she didn’t ask me. I was too terrified to learn so I didn’t come out with any maths skills. I loved English though. My favourite teacher was my English teacher and I couldn’t wait for my turn to read out loud.”

The children were assigned to different houses, named after the Hospital’s founder Coram and its prominent supporters, Handel, Hogarth and Dickens. Ruth remembers that she was in the ‘Coram’ house and that the children were awarded points for things like good speech and smart appearance.

Ruth says her years at the Hospital gave her a “good foundation” but she felt that she was lacking in some basic life skills: “It took me a long time afterwards to feel or to become independent. For years I would never take buses because I didn’t have any sense of what was north or south.”

One thing Ruth loved at the Hospital and took with her throughout life was swimming. She says: “The Hospital had an indoor pool and it was compulsory for all the children to learn to swim. I enjoyed it enormously. So much so that I took exams later to become a swimming instructor and taught it up until I was 75.”

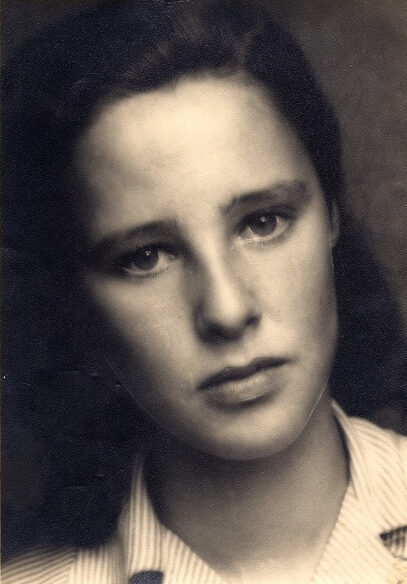

Photo of Ruth as a young woman

Birth parents

Ruth remembers the children would often talk together about why they had come to the Hospital: “We wondered why we were there. We certainly weren’t familiar with the word ‘illegitimate’ at that time. We imagined our mothers must have done something bad, or that they were too important to take care of us. I imagined I was the daughter of a film star of someone important. We never talked about our fathers though, only our mothers.”

Ruth didn’t know anything about her birth parents, until she decided at the age of 50 to access her records out of curiosity for her past. She discovered that her mother was Welsh, well-educated and had been working away from home at a hotel in Leicester at the time of Ruth’s birth. Ruth wasn’t able to find out much about her father, only that he was a commercial traveller from Golders Green and that he met her mother whilst staying at the hotel.

After further research, Ruth found that her mother was born in 1901, and was in her mid-thirties when she became pregnant. She hadn’t been honest about her age when appealing to the Hospital for fear of being judged for being older and the risk of her application being rejected, so she wrote on the forms that she was 29.

Ruth’s mother had written regular letters to her asking how Ruth was getting on and the secretary at the Hospital would write back and say she was doing well. Ruth never saw the letters as a child, she only read them when she was supported by Coram to access her records years later. Ruth also discovered that her mother didn’t marry until 1961, when she was 60 years old and didn’t have any more children. She had passed away before Ruth had accessed the records but she says even if her mother had still been alive at the time, she doesn’t know if it’s something she would have wanted to follow up on.

After the war and leaving the hospital

Ruth remembers that things started to feel very different at the Hospital after the war had ended. The children could stay with their foster families during the summer, younger teachers started to come in and the children were allowed to go outside the grounds for the first time and into the local town to learn about life outside the Hospital.

Ruth recalls the day that she left the Hospital in 1950: “We were presented with a bible that had the date of leaving. I’ve still got mine. I remember the sermon that said we were ‘standing at the crossroads of life’… I was terrified of the outside world at that time.”

Ruth subsequently attended Watford Grammar School where she took her O-Levels and then went to Camden School For Girls. She then decided she wanted to become a nurse, a profession she believes she was drawn to because of “the rules and the uniform” which echoed her very regimented early life at the Hospital. She says: “I lived in the nurses home until I finished my training, which was run by a strict ‘Home Sister’. I didn’t find the rules difficult, I was used to that way of life and being told what to do.”

Ruth says she felt the stigma of growing up in the Hospital for a long time after leaving: “I went to enormous lengths to hide it, I didn’t want to reveal my past. I would make vague replies when people asked questions. At one time in my life, I thought I was going to get engaged to a medical student and then there was discussion about the announcement in the newspaper. His parents said to me ‘But what will we write for you? Daughter of whom?”

Ruth now has a big family of her own: three daughters, eight grandchildren and one great-grandson and says she sometimes talks to them about her early life, and has taken them to the Foundling Museum so they can better understand what life was like for her growing up at the Hospital.

She became and continues as a governor of Coram, helping the development of contemporary services, including participating in programmes with young people leaving the very different care system today.

She says:

“I have mixed feelings about my time at the Hospital. I think their aims were good. In some respects we were very lucky, we had a swimming pool, a gym and acres of land so our physical health was greatly enhanced, but there needed to be more emphasis on our mental wellbeing.”

Ruth believes that it is very important to share the stories of the children who attended the Hospital with future generations so that we can all learn from their experiences.