The Foundling Hospital archive contains materials dating from its establishment in 1739. It opened for admissions on 25th March 1741. On this opening night, it opened its doors at 8pm and remained open until it reached full capacity and 30 children had been admitted (18 boys and 12 girls). The criteria for this night were as follows:

‘that no child exceed in age two months nor shall it have the French Pox or disease of like nature; all children to be inspected and the person who brings it to come in at the outer door and not to go away until the child is returned or notice given of its reception. No question asked whatsoever of any person who brings a child, nor shall any servant of the Hospital presume to enquire on pain of being dismissed.’

Over the years, the capacity, process and criteria for admittance changed from this opening night. Many more children were admitted when the hospital building was completed, and one key addition to the admission process involved the writing of petition letters.

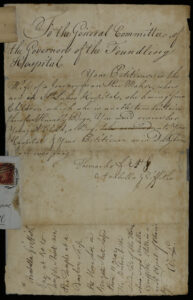

From 1763 mothers had to ‘petition’ by writing a letter to the Governors to state why their child should be taken into the Foundling Hospital. They usually presented their case by giving reasons why they could not care for their child, plus a character reference from someone the Governors at the Foundling Hospital might consider to be a reputable person. It was deemed essential that the mothers were of ‘good character’. The staff at the Foundling Hospital would investigate the applications, looking in to the circumstances around the child’s birth and making judgements on the moral character of the mother.

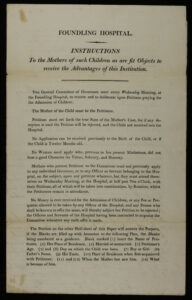

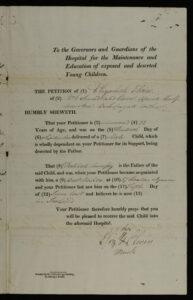

The printed form that was introduced in 1813

Information found in these letters include the name of the mother, along with her age and marital status. The date of the child’s birth and the name, occupation and whereabouts of the father, if known, plus a last date of contact can also be found. The majority of the letters were written by, or on behalf of the mothers. Where a woman couldn’t write, she would mark an ‘X’ next to her name that had been written by the letter writer. Some letters were written by other family members, friends, neighbours or employers. The letters often contain heart-breaking detail as the petitioners explain their situations and why they cannot look after the child themselves.

In 1813 a printed form was developed by the Governors for mothers to complete when submitting their petitions. On the reverse was a list of ‘instructions’ to the petitioner. These documents would also be supported by a character reference along with written testimony from the mother.

Staff at the Foundling Hospital wrote on the letters, often including notes on their investigations and the outcome of these. Some petitions were successful and gained admittance for a child to the Foundling Hospital, others were unsuccessful and the Foundling Hospital was unable to take the child in to their care. The numbers of spaces available at the Foundling Hospital varied and would dictate how many children could be taken in. (This was not the case for a period of four years from 1756-1760 called the General Reception, when in exchange for government funding, the Foundling Hospital had to accept any child brought to them.)

Reasons why a child may, or may not, be admitted varied. The Governors talked about assisting ‘proper objects of charity’, -those living in poverty. So the financial situation of the petitioner was considered. Others factors which would be taken in to account included: the social disgrace of being a single mother at this time, and the inevitability of unemployment and homelessness that came from this social stigma; desertion by the father of the child; seduction* and assault. The Governors accepted the children of single women, widows and married women.

A handwritten petition from Arabella Griffiths, along with notes made on letter by FH staff

Typical reasons for petitions not being accepted included: being unsuccessful in the ballot process; a mother failing to provide a character reference with her petition that was considered suitable; perceived inconsistencies in a mother’s evidence (which would be taken to suggest she was lying); any suggestion that the mother had been the long-term mistress of the reputed father.

The petition letters provide insight into the lives of the mothers and the situation they found themselves in. They also give a real sense of the attitudes of the Governors of the Foundling Hospital towards them, as well as reflecting morality in society more broadly at that time.

Some of the petition letters have recently been digitised at the London Metropolitan Archives and are part of our ongoing transcription project on the Zooniverse platform. To find out more about this, and to see some petition letters, sign up to be a transcriber.

To find out more about the ballot system and changes to the admissions process at the Foundling Hospital over the years, see our article, Admissions the the Foundling Hospital.

To find out more about recent conservation work that has been carried out on some of the petition letters, see our blog on conserving petition letters.

*The word ‘seduced’ appears frequently in our archives, especially in petitions from mothers to the Foundling Hospital. From the 15th century onwards, its specific meaning in English was to entice a woman who had not been sexually active to have sex outside marriage (termed ‘criminal conversation’). The nearest equivalent today to its usage in those earlier times would be ‘grooming’ — although this is not an exact equivalent. Mothers applying to the Foundling Hospital made it clear to the governors that these were their circumstances, in order to have any chance of their children being admitted.

Today the word seduction is used far more broadly and does not carry the connotations it did in earlier centuries. Its usage in eighteenth and nineteenth century petitions from mothers to the Foundling Hospital point to the widest range of sexual encounters, including consensual sex, sexual assault, and rape.