The case of Joseph Palmer, Foundling Number 17363, and his mother Jane Evans is an unusual one that we do not often come across in Coram’s Foundling Hospital Archive. Through tracing his journey throughout the collection we can see a fascinating story start to emerge.

The Petition

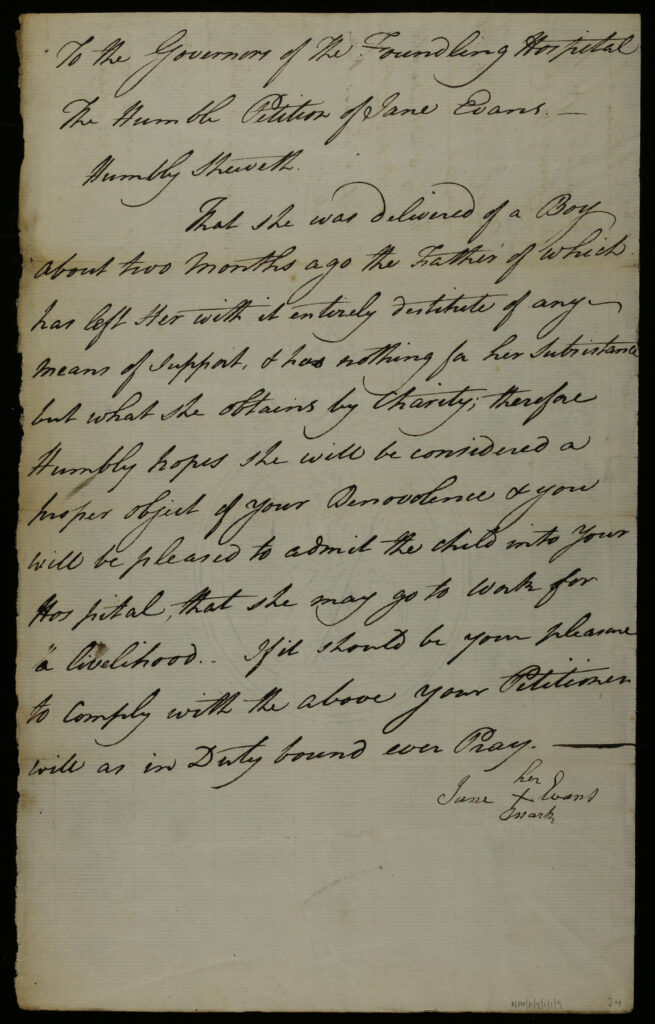

Joseph’s story in the archive begins in 1778 with his mother’s petition letter to the Foundling Hospital. Jane Evans’s situation reflected that of many women who wrote to the Hospital:

‘She was delivered of a Boy about two Months ago the Father of which has left Her with it entirely destitute of any means of support & has nothing for her subsistence but what she obtains by Charity.’ – Petition letter A/FH/A/08/001/001/009/074/a1

Unable to support her son financially following the disappearance of the father, Jane offered her child to the Hospital in the hopes that she could ‘go to work for a livelihood’ while he was cared for. It is clear from the phrasing of the letter that someone else wrote the letter for her, as she was illiterate, signing her mark with an X at the end of the letter.

With her petition, she was required to have a reference to support her application. For Jane, this came from her employer John Martindale, the owner of White’s Chocolate House. The letter suggests that Jane had been a servant there, but was not working at the time. It is likely that she stopped working at the Chocolate House after giving birth to her son. Martindale gave a positive assessment of Jane’s character, referring to her as ‘a very honest, sober, industrious person’ and asserting that she is in ‘Great Distress’.

Thanks to his reference, Jane’s baby was admitted into the Hospital on 5 August 1778 at two months old. He was baptised with the name Joseph Palmer and sent to wet nurse Rebecca Palmer shortly after.

Jane Evan’s Petition letter – A/FH/A/08/001/001/009/074/a1

White’s Chocolate House

White’s Chocolate House, usually known as White’s, is the oldest gentleman’s club in London. Chocolate was a luxury in the 1700s and was only available as a drink in England. This led to the formation of chocolate houses that served it to those who could afford it. White’s was the unofficial headquarters of the Tory party during Jane’s employment there.

Decades earlier, in 1753, the Sub-Committee minutes mention the Chocolate House in relation to a performance of Handel’s Messiah in the Foundling Hospital’s chapel, which would turn out to be a financial success. The minutes state that tickets were to be sold at White’s and several other gentlemen’s clubs, probably in an attempt to promote the Hospital and inspire patronage from the most influential men in London.

The Hospital’s 1200 tickets were soon sold out. Gentlemen at White’s Chocolate House must have attended the concert and likely became donors to the Foundling Hospital as a result. It is therefore possible that Jane may have known about the Foundling Hospital through working at the club.

A second chance

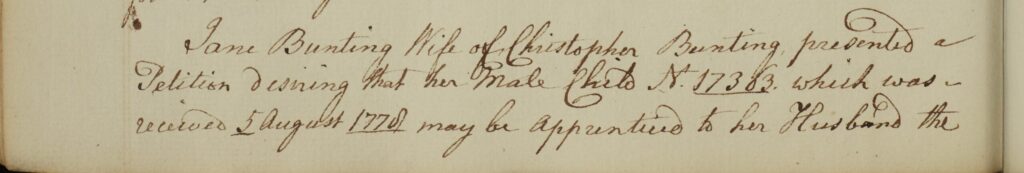

Joseph appears again in the archive in 1782, when his mother and her new husband returned to the Foundling Hospital to present a new opportunity for the young boy. On 11 May 1782, the Sub-Committee Minutes record that Jane and Christopher Bunting wished to claim Joseph back so that he could be apprenticed to Christopher, who, Jane said, was his father. The Apprenticeship Register confirms that the committee agreed to this and that Joseph was employed by his father to undertake ‘household work’.

Sub-Committee Minutes – A/FH/A/03/005/016/148

This is one of the few examples in the Foundling Hospital’s history of a child being claimed back by their mother and being given a second chance of having a family. Joseph’s story is also unusual because he was apprenticed at an extremely young age.

At only four years old, Joseph was far below the age that most Foundlings would have been apprenticed. Legal adoption was not established in the UK until 1926; therefore the only way Christopher could gain any kind of custody over Joseph would have been through apprenticing him. Apprenticeships were used as a way to unofficially ‘adopt’ a Foundling child, which may explain why Joseph was apprenticed at such a young age. He would not actually start his apprenticeship until he was around 11 years old.

Christopher was recorded as working as a porter in Soho, meaning he was employed to carry heavy cargo and luggage. He would have offered his services to a number of businesses in the area. It is unclear whether Christopher was the biological father, who left Jane ‘entirely destitute’ when Joseph was born. However, marriage records from the City of Westminster record a marriage between a Jane Evans and a Christopher Bunting a year after Joseph was born. Whatever happened during those four years, it is clear that by 1782, Christopher was successful enough at work to allow Jane to claim back her child, and to provide Joseph with a family and the skills to make his own living.

Bibliography

Westminster Archives:

Parish Marriages (STG/PR/7)

Coram Foundling Hospital Archive:

Petitions Admitted to Ballot: Admitted and Rejected

A/FH/A/08/001/001/009/074/a1

A/FH/A/08/001/001/009/074/a2

General Register

A/FH/A/09/002/005/027

Sub-Committee Minutes

A/FH/A/03/005/001/193

A/FH/A/03/005/016/148

A/FH/A/03/005/016/149

Apprenticeship Register

A/FH/A/12/003/002/185

Copyright © Coram. Coram licenses the text of this article under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 (CC BY-NC).