Philippa Smith, who used to work as Head of Collections at London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), has been working with the Foundling Hospital records for a number of years now. She takes a closer look at the medical records of the Foundling pupils and what they reveal about living conditions at the Foundling Hospital.

I have recently retired as Head of Collections at London Metropolitan Archives (LMA) and was closely involved with the Voices Through Time project as the main point of contact between Coram and LMA. However, my involvement with Coram’s Foundling Hospital archive began long before then. Pretty much everyone who works at LMA will have some contact with the Foundling Hospital archive, one of the most accessed collections held by LMA. Every time I worked in the Archive Study Area doing late duty or on a Saturday as senior manager, there would be someone – maybe a family historian, independent researcher, student or academic – looking at Foundling Hospital material, eager to share their excitement at what they had found. I was aware of the fragile nature of much of the collection through involvement with conservation and LMA’s access to unfits programme.

A conservation survey of the Foundling Hospital archive had identified in particular the poor condition of the records relating to the health of the foundlings, of which some were unfit for consultation. A grant was obtained from the Wellcome Trust Research Resources in Medical History programme to conserve, digitise, and make them accessible; the project ran 2017-19. One of the engagement activities funded by the grant was a free public exhibition Child Health in London at LMA from 9 November 2018 until 10 April 2019. The exhibition had at its core the Foundling Hospital medical records which record in a largely unbroken sequence and in meticulous detail the health of the foundlings and the treatment they received over 200 years from 1741 when the first child entered. It also presented the records in the wider context of the history of the health of the capital’s children.

Foundling Hospital showcase in LMA Child Health exhibition

The founding vision of Thomas Coram was the protection and welfare of the foundlings, and by promoting their health and education to enable them to support themselves through work. One of the original governors of the hospital and a friend of Thomas Coram was the eminent physician Dr Richard Mead. He was a pioneer of inoculation against smallpox and an advocate of giving children fresh air. These ideas are seen being put into practice in the records which illuminate a wide range of topics beyond child health and welfare. New methods included care or cure for childhood diseases, mortality, disability, pain, emotions, institutional care and experience, and dental and ocular practice.

I was involved in curating the Foundling Hospital contribution to the exhibition including a showcase of original items and a banner and on-screen display telling the story of an individual foundling Theodore Barrow.

I found all the records fascinating, but I was most interested in the records of treatment. Inoculation against smallpox was used at the Foundling Hospital from the 1740s. Inoculation was the deliberate introduction of matter from smallpox pustules into the skin, which generally produced a less severe infection than naturally-acquired smallpox and so induced immunity to it. Edward Jenner later adapted the practice of inoculation, developing a safer, more effective technique he called vaccination. Having observed that people who caught cowpox gained immunity from smallpox, he successfully trialed the technique in 1796. The exhibition displayed an Inoculation Book* stating that vaccination was introduced into the Foundling Hospital in 1801 and that on 10 April, six boys were ‘inoculated’ with cowpox matter from the arm of Hannah Dodson. It was noted that none of them developed an infection.

Inoculation Book from the Foundling Hospital archives

In the 20th century, the Foundling Hospital used another new treatment, light therapy, and recorded this in a Violet Ray Record Book 1937-49**. Physicians had used both natural sunlight and artificially-generated light from the 1890s, and by the 1920s it was understood that the light’s actinic rays – its blue, violet and ultraviolet light – could activate the production of vitamin D in the body. By the 1930s, light therapy was well-respected as a treatment for all sorts of diseases, especially those of the skin and deficiency disorders like rickets.

Foundlings suffered from a range of skin diseases and deficiencies, as seen throughout the records from the tabulated weekly reports of the sick in the infirmary from the mid-18th century to the detailed medical report books of the late 19th and 20th centuries. It is also evident in a dental examination book 1900-1915***, which not only includes information about foundlings’ teeth and dental treatment, but also about their general health and nutrition. Poignantly, a few entries are annotated with a note about the patient’s service in the First World War – including some killed in action 1914-15. This is perhaps reflective of the dentist’s ongoing concern for his young patients and their fate.

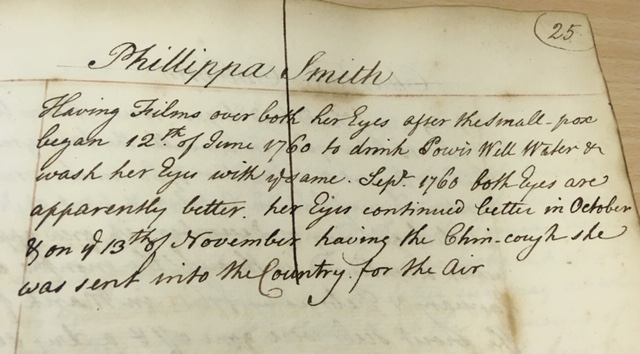

However, not all the treatments adopted by the Foundling Hospital were scientifically-proven. One such is treatment with Powis Wells Water and notes of this survive (1759-62)****. The Powis Well (originally sited at the north west end of what is now Great Ormond Street Hospital, close to the then Foundling Hospital) was discovered in the early 18th century. Powis Wells Water was regarded as having healing properties, especially for eye complaints, skin conditions, and scorbutic and leprous disorders. It was administered both as a drink and to wash affected parts, but from the apothecary’s notes it seems – unsurprisingly – to have been ineffective and was subsequently abandoned. But the fact that it was tried at all and that detailed notes were taken seems to be to be indicative of the Founding Hospital’s attitude to medical treatment and the foundlings’ health.

Powis Wells Water health notes from the Foundling Hospital archive

Further reading

Dr Eric Schneider looks at the health of London children under institutional care, 1890-1916

Conservation of a prescriptions book dated 1762-1794, from the Foundling Hospital archive

* Record number (A/FH/A/18/008/014)

** Record number (A/FH/A/18/013/001)

*** Record number (A/FH/A/19/001/001)

**** Record number (A/FH/A/18/009/001)