In 1763, the Foundling Hospital amended the admission conditions to require a petition letter from the child’s parent, explaining their circumstances and why their child should be admitted. In many cases, the letter came from the mother, who had often been abandoned by the child’s father and left with no means to care for their baby.

However, there are some rare instances in Coram’s Foundling Hospital Archive where it is the father who petitions for his child’s admission. Samuel Norbury is one such example and his letter reveals a great deal of what life as a single father could be like in the 18th century…

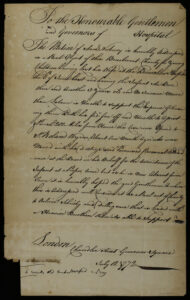

Samuel Norbury’s petition letter

On 18 July 1772, Samuel Norbury wrote to the Governors of the Foundling Hospital to request the admission of his one-month old baby, the younger of his two children. In his letter, he explained that his wife had died during childbirth at ‘the Brownlow Hospital’ in Holborn, London (also known at the time as the Lying-In Hospital for Married Women) and that, as well as the newborn baby, he had a three-year-old in his care. His work as a labourer was not enough to pay for a wet nurse for his children and he had no other support to draw upon, being 200 miles from the parish from which he could theoretically receive parish relief.

He stated in his letter that he had already approached ‘Sir Roland Wynn’ about his case and that this gentleman had promised to support his case in front of the Board of Governors. However, when the letter was written, the gentleman was out of town and therefore unable to attend the Board meeting, hence Samuel’s personal plea for the Governors’ charity.

Thanks to the Billet Book and General Register in the archive, we know that his petition was successful and Samuel’s child was admitted into the Foundling Hospital on 8 August 1772 as number 16712. He was baptised under the name James Tagg and sent to the wet nurse the next day.

Samuel Norbury’s petition letter

The Poor Laws

16th century illustration of a gentleman giving alms to a beggar

The letter raises two interesting points about the factors surrounding this admission. The first is the reference to parish relief, which highlights the practical implications of the Poor Laws in the 1700s. Legislation regarding relief for the poor can be traced back to 1536, where laws were passed regarding relief to the ‘impotent poor’. In 1601, this legislation was formalised in the Old Poor Law, which established an authorised route whereby the parish was expected to provide financial relief to those who either could not work or were unable to work due to a loss of their trade.

In 1662, the Settlement Act was added to this legislation and defined which parish a person could claim relief from. This would often be the parish where they were born or where they worked, provided they had worked there for at least a year. In Samuel’s case, his designated parish was over 200 miles away from his current residence in Grosvenor Square, London. Therefore it was too far for him to travel, with two young children, to claim poor relief, even though he would have been eligible as he could prove that he was trying to find sufficient work. Despite the aim of the Poor Laws to provide relief for the ‘deserving’ poor, this is one of potentially many cases where an eligible person fell through the gaps due to geographical barriers that the Laws did not account for.

Sir Rowland Winn, 4th Baronet of Nostell Priory

The second interesting factor of this letter is the reference to ‘Sir Roland Wynn’, who Samuel directly petitioned. This is most likely Sir Rowland Winn, 4th Baronet of Nostell Priory, who was a Governor of the Foundling Hospital at the time. Sir Rowland’s family had gained their wealth through London’s textile industry during the Tudor period, which later placed them among the English artistocracy. Sir Rowland is mentioned in the Sub-Committee minutes and seems to have been heavily involved in the Foundling Hospital. For example, on 29 January 1755, the minutes note that Sir Rowland had been asked to provide linens for the Hospital’s use and he had then advised the Treasurer on their delivery. In 1762, the minutes mention him again in relation to his factory in Yorkshire making the uniforms for the Hospital.

Sir Rowland was primarily concerned with the Ackworth branch hospital, in Yorkshire, and acted as its Treasurer during the hospital’s lifetime. (Nostell Priory is in Nostell, West Yorkshire, not far from Ackworth.) The Ackworth Foundling Hospital opened in 1757 after government funding of the London hospital required admission of all children in need. This caused a sharp uptake of children and led to the opening of several branch hospitals outside London. The Ackworth branch hospital later closed in 1773 following the withdrawal of the government grant.

It is therefore no wonder that Samuel decided to approach Sir Rowland Winn personally about his case, perhaps hoping that his influence as a Governor would help this exceptional case of a widowed father rather than a single mother. We cannot know for certain why Samuel approached Sir Rowland specifically. However, if Samuel’s birth parish was 200 miles from London, this would place it within the region of Yorkshire, where the Ackworth Hospital and Sir Rowland’s factory were based. Therefore, it is possible that Samuel decided to approach Sir Rowland knowing that he was a key figure in his parish’s branch hospital. It is also unclear from the Foundling Hospital records whether Sir Rowland’s support of his case influenced the decision to admit Samuel’s child. It is possible that it helped to bring Samuel’s letter to the attention of the Governors and allow his case to be heard and later accepted.

Bibliography

Coram’s Foundling Hospital Archive:

Petitions Admitted to Ballot: Admitted and Rejected

- A/FH/A/08/001/001/003/023/a1

Billet Books

- A/FH/A/09/001/181/109

- General Registers

- A/FH/A/09/002/004/401

Sub-Committee Minutes

- A/FH/A/03/005/002/041

- A/FH/A/03/005/005/102

Websites:

Licensing information

Copyright © Coram. Coram licenses the text of this article under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 (CC BY-NC).