Coram’s Foundling Hospital Archive contains a letter from James Edward Austen-Leigh, the nephew of novelist Jane Austen. The Hospital had contacted him for information about two of his servants, who allegedly became the parents of an illegitimate child while in his employment.

Bray Vicarage, 1861

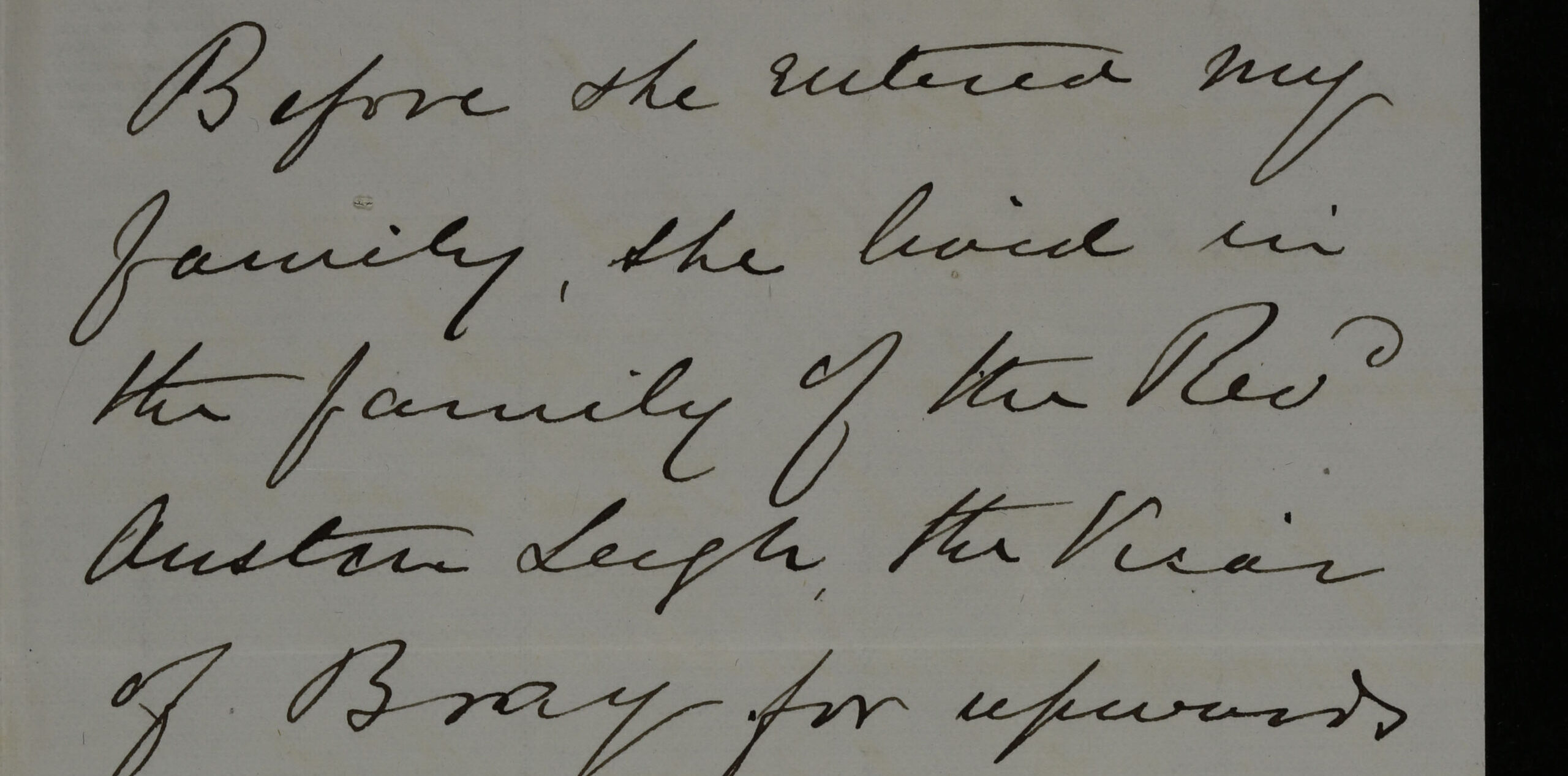

Fanny Sarah Sharp and James Butchard met as servants at Bray Vicarage, Berkshire, the home of the Reverend James Edward Austen-Leigh (1798-1874). He had taken up residence there in 1853 when he became vicar of St Michael’s Church, Bray, a position he held until his death.

Austen-Leigh was the son of Jane Austen’s oldest brother and is remembered today as her first biographer. He grew up just four miles from Steventon, Hampshire, where Jane Austen (1775-1817) lived until 1809. While vicar of St Michael’s, he published two editions of A Memoir of Jane Austen (1870, 1871).

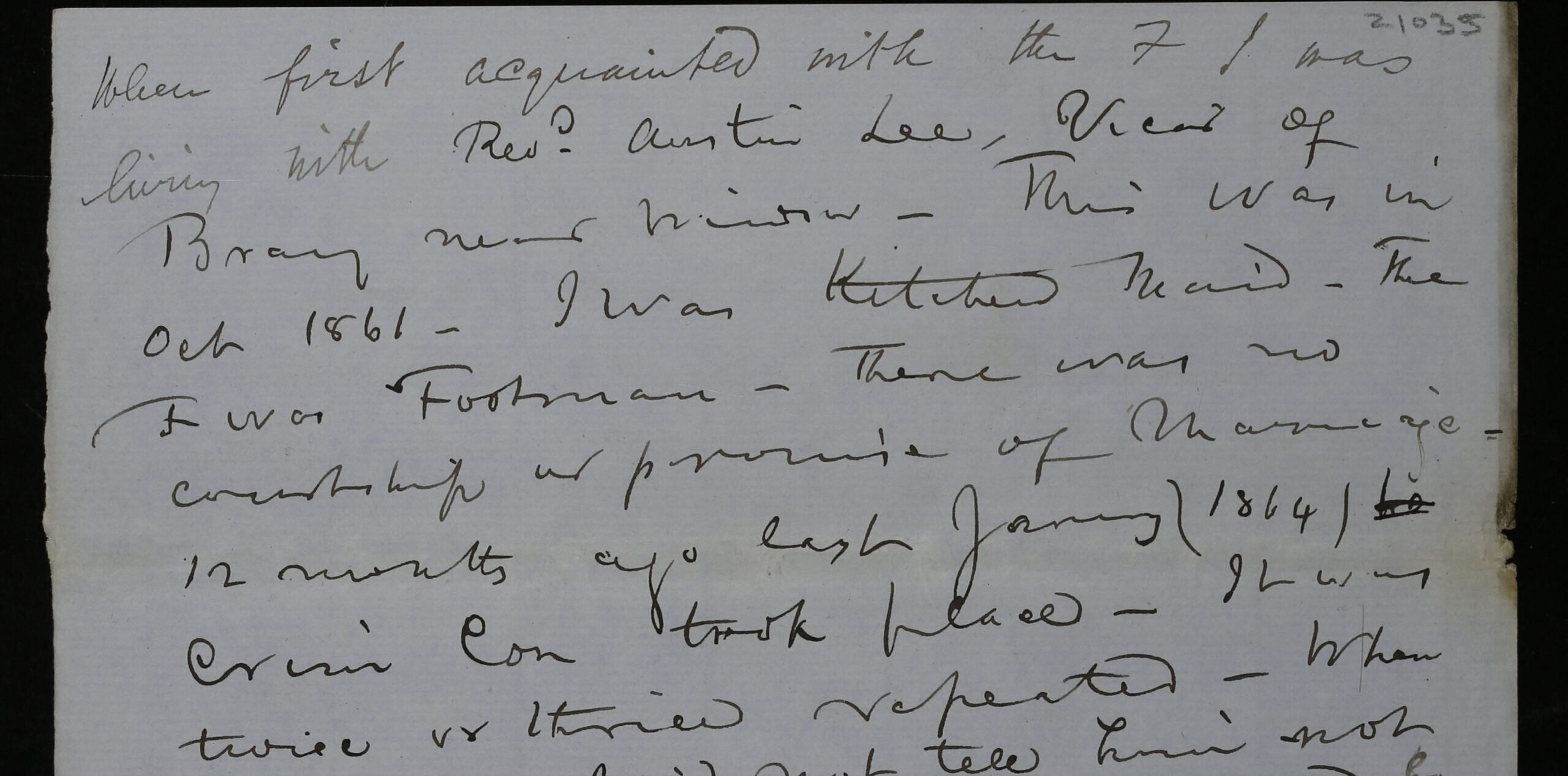

On census night in April 1861, Austen-Leigh was at Bray Vicarage with his wife Emma, five of their 10 children, and seven servants, none of whom were Sharp or Butchard. Aged 16, Sharp was working in a country house outside Windsor as a kitchen maid for a wealthy widow. Sharp was from Bray, where her father made hurdles (portable fencing for penning sheep). It is likely that James Butchard was the 17-year-old footman from Tilehurst, who was in service to a magistrate in Kingston Lisle. By October 1861, both Sharp and Butchard were employed in these same roles at Bray Vicarage.

Fanny Sharp’s account of events, 1863-64

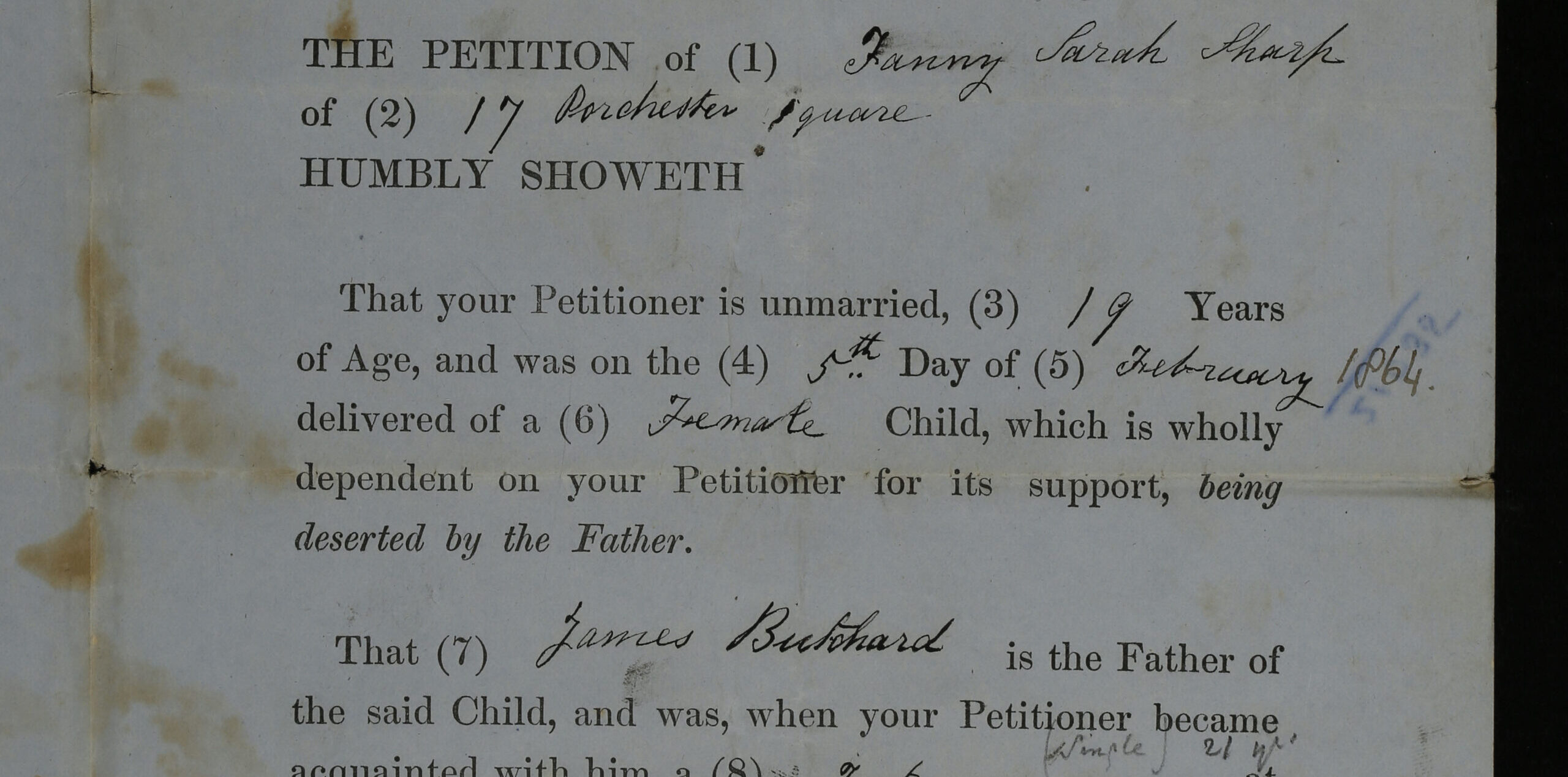

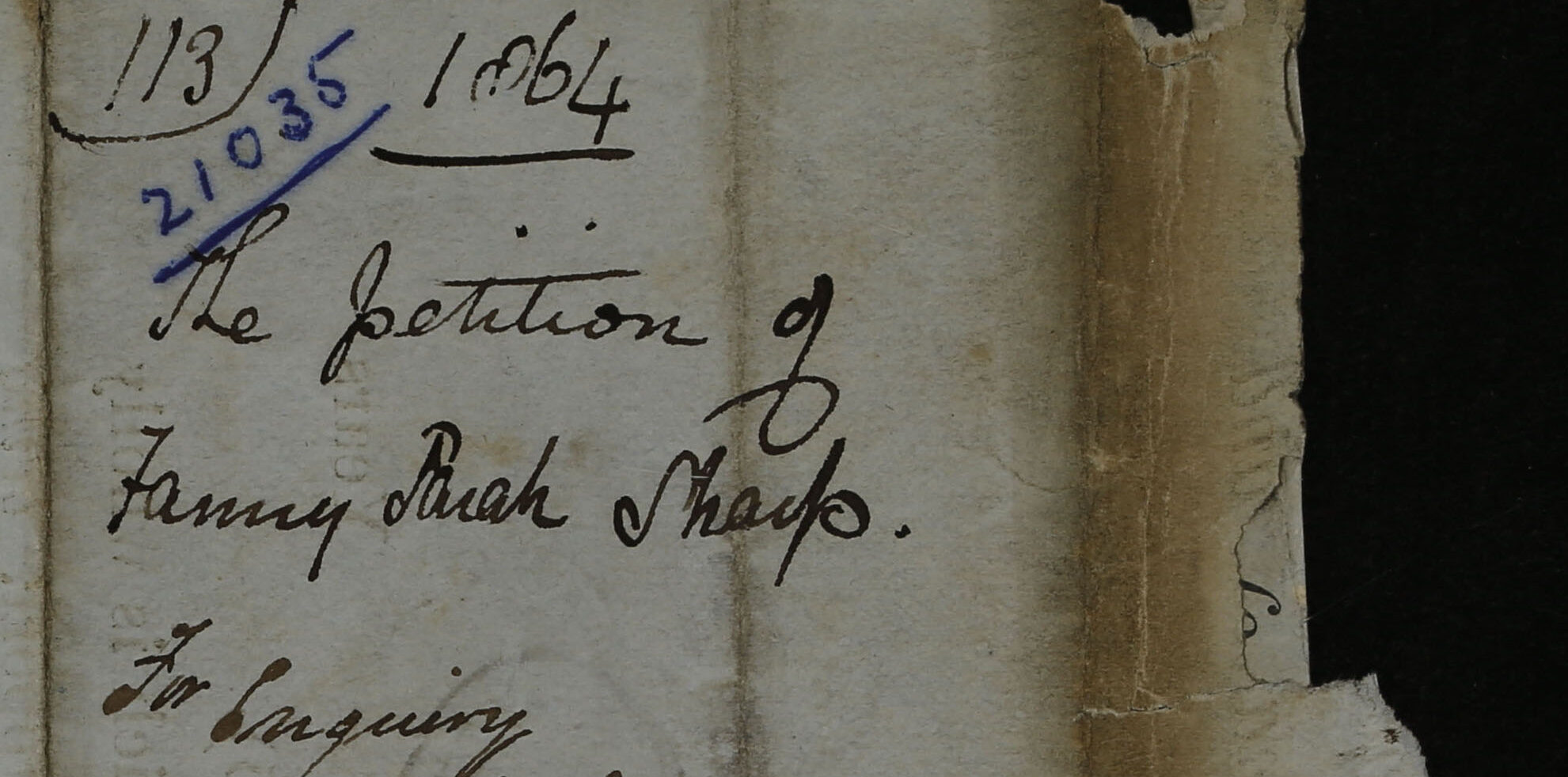

Fanny Sharp was 19 years old and unmarried when she gave birth to her daughter on 5 February 1864 in London. In June, she visited the Foundling Hospital to petition for the admission of her baby. She provided a statement about her situation, written down by a staff member, and signed a petition form in her own handwriting.

Her statement said that her physical relationship with Butchard had started in January 1863, although ‘there was no courtship or promise of marriage’. She must have been distressed upon discovering she was pregnant. She knew the shame she was about to bring on herself, her family, and the Austen-Leighs, whose vicarage should have been the model of propriety.

It seems that Sharp decided not to tell anyone, not even Butchard (‘not liking to do so’), and to find a way to leave Bray. She successfully applied to become cook for the Reverend and Mrs Lingwood in Maidenhead, about two miles away. She arrived there in November, but had to leave six weeks later, ‘not being able to do my work’.

Sharp then went to stay with her sister, Mrs Swan, in Paddington Green, London. She saw Butchard around two weeks before the birth, but her statement gives no details about this meeting. After she recovered from the birth, Sharp began working as a cook for Captain and Mrs Harris of 17 Porchester Square, London. They would keep her on, she said, if the Foundling Hospital accepted her child.

Corroboration of her account

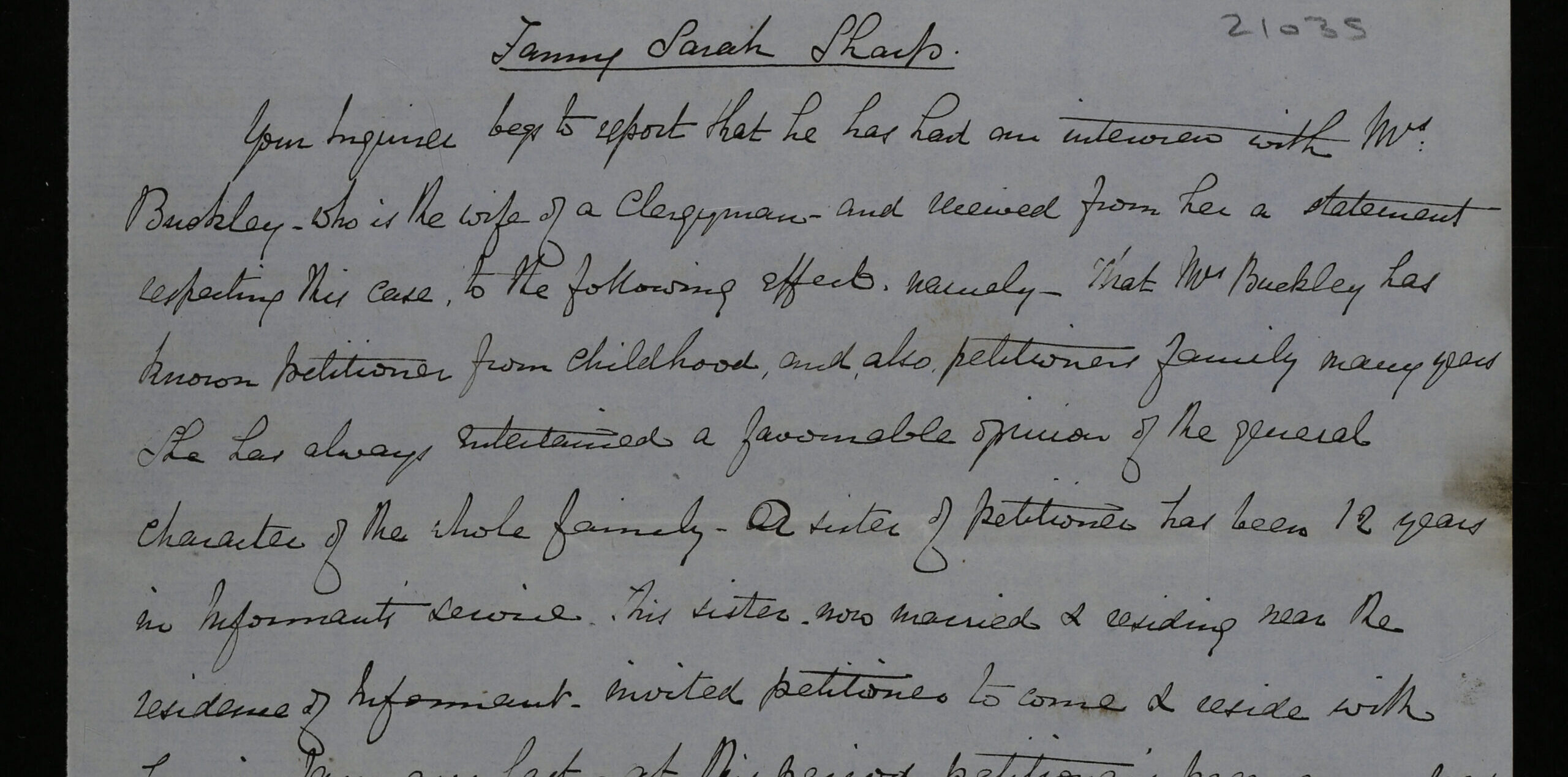

James Twiddy, the Foundling Hospital’s investigator, then set about verifying her account. He visited Mrs Swan, Mrs Harris and Mrs Buckley, a clergyman’s wife who had employed Swan for 12 years and who was acquainted with the Austen-Leighs. Twiddy wrote to the doctor who delivered the baby and Sharp’s two previous employers.

Although living in London at this period, Buckley had known Sharp’s family for many years and had ‘always entertained a favourable opinion of the general character of the whole family’. Buckley had been unaware of Sharp’s condition until 5 February, when the two sisters were visiting her. Sharp ‘was suddenly taken ill’. A doctor was called and discovered she was in labour. Sharp returned to her sister’s house, where she gave birth. The doctor wrote to Twiddy, ‘I have no hesitation in saying that it was a first labor [sic]’, indicating that Twiddy had asked about this.

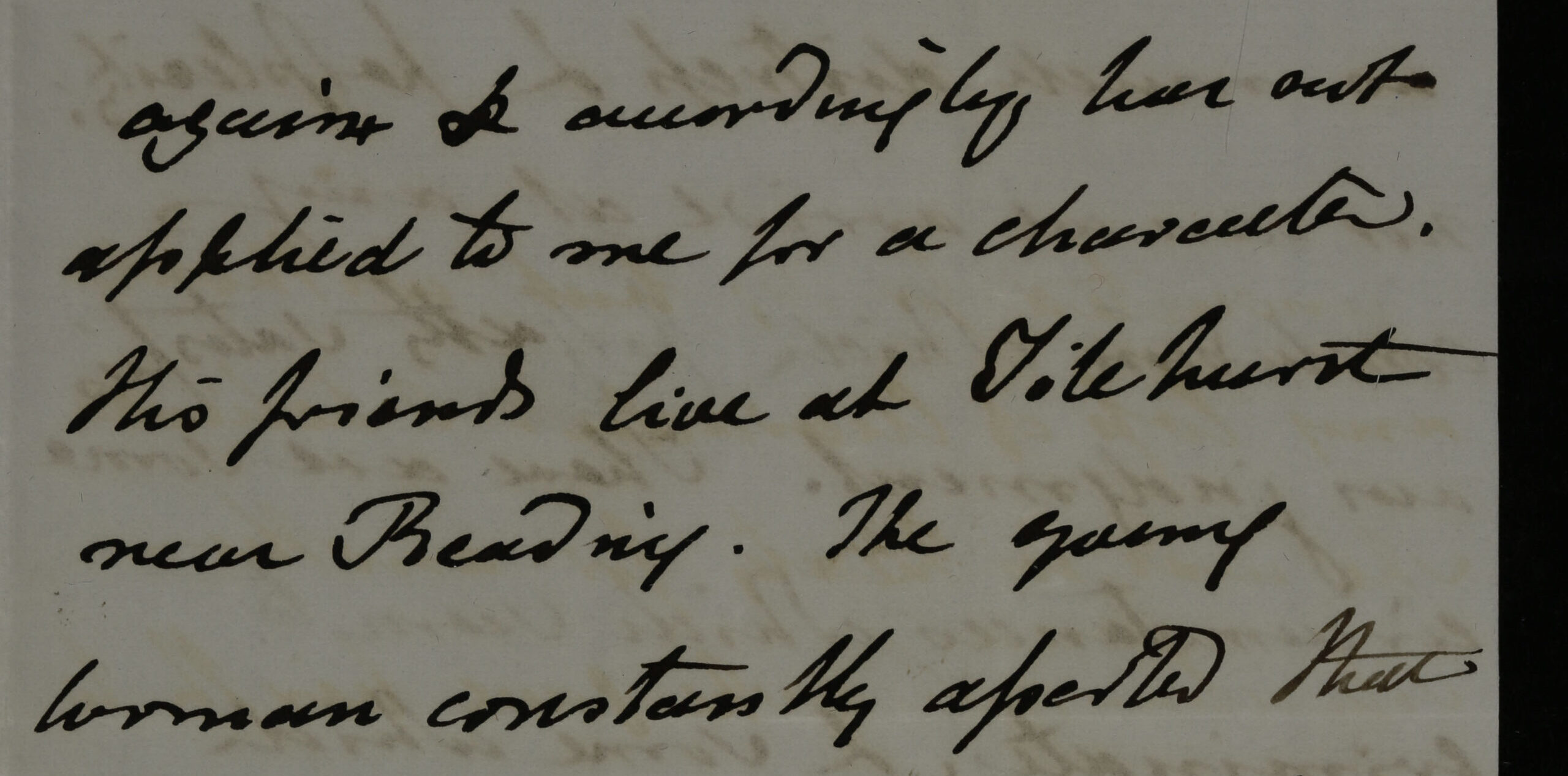

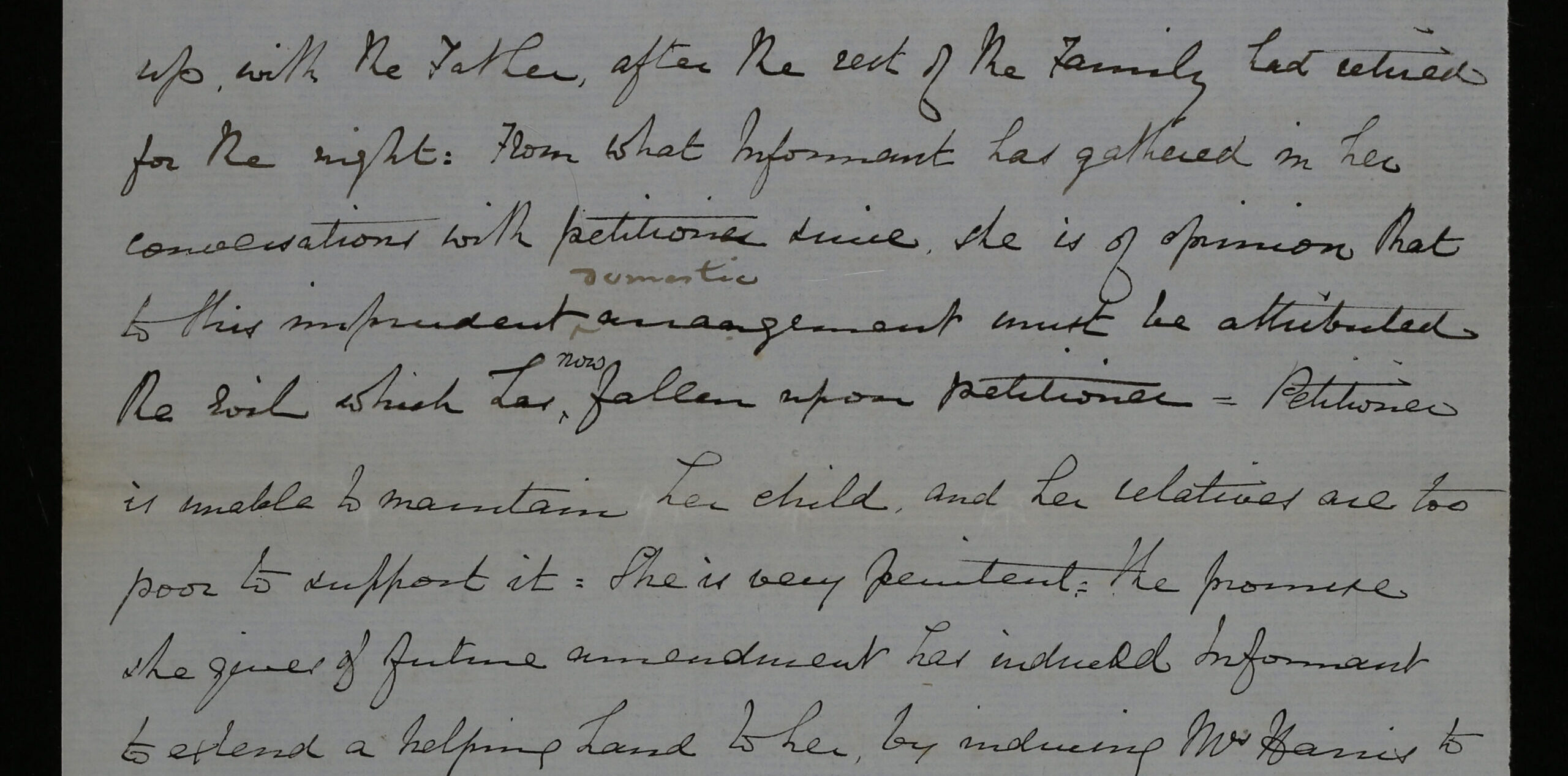

Soon after the birth, Swan visited Austen-Leigh to ask him to investigate the matter, but Butchard ‘denied the paternity’. Buckley reported that the Austen-Leighs had seen nothing to suggest a relationship between Sharp and Butchard, but that the two of them had been allowed to stay up after the family had gone to bed. Buckley concluded, ‘To this imprudent arrangement must be attributed the Evil which has now fallen upon [the] petitioner’.

She confirmed that Sharp was ‘unable to maintain her child and her relatives are too poor to support it’. Wishing to help Sharp because she had been ‘very penitent’, Buckley had recommended her to Mrs Harris, who had taken her on as cook. Harris gave Twiddy a favourable report of Sharp’s conduct in her household.

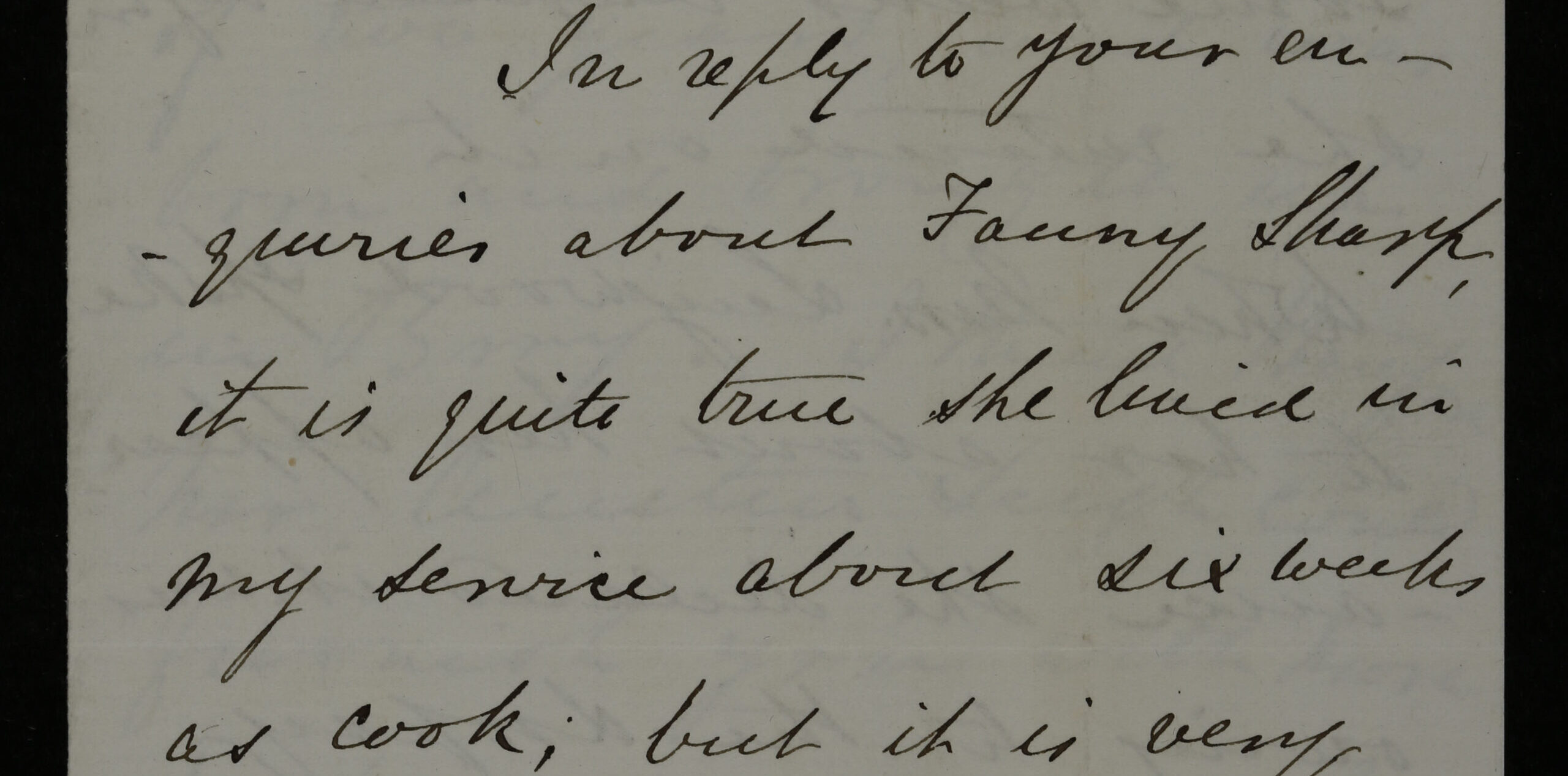

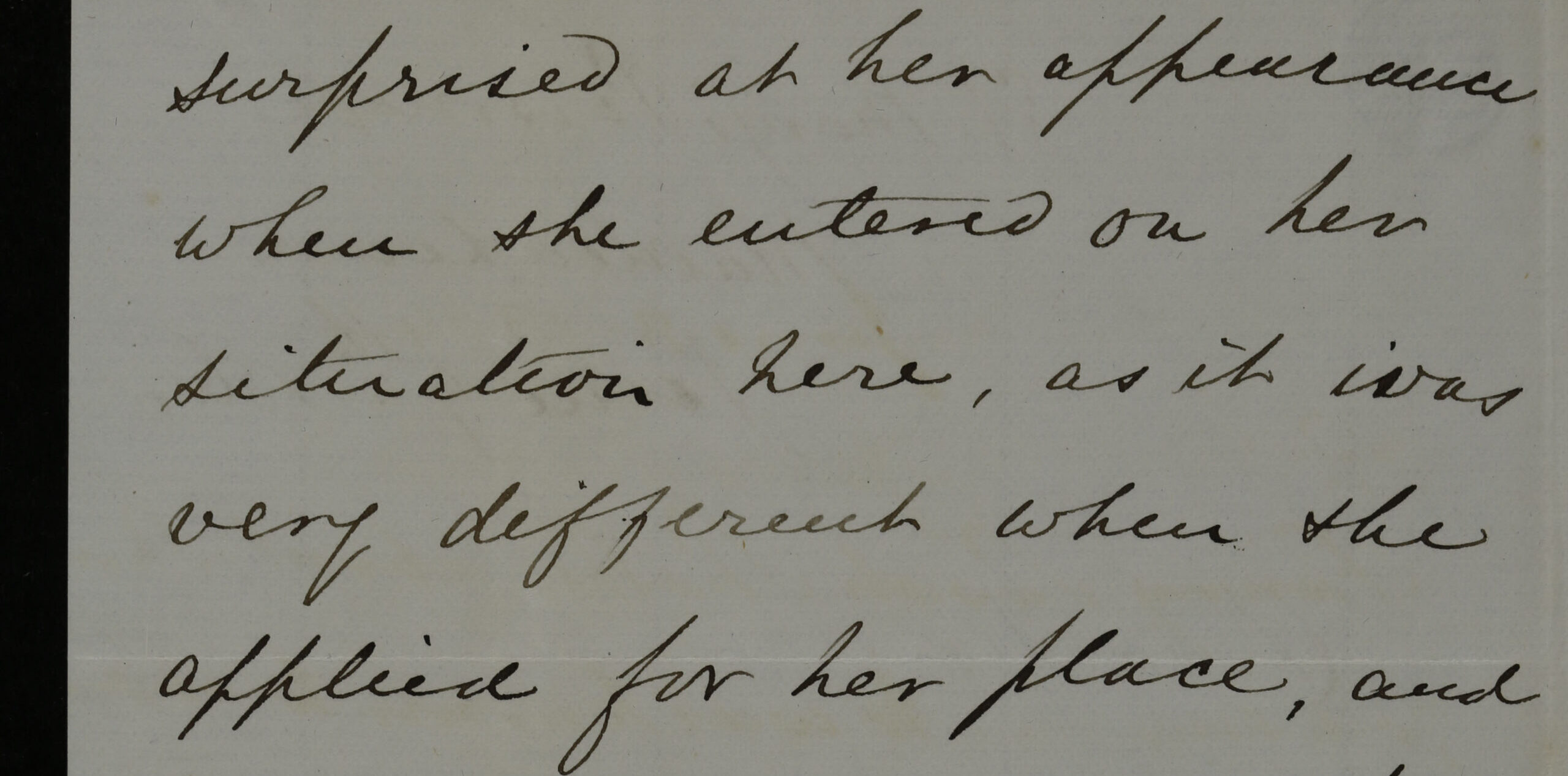

In contrast, Revd Thomas J. Lingwood was not pleased at having been deceived. He and his wife had been surprised at the change in Sharp’s appearance when she took up her position. Sharp told them she was suffering from dropsy (fluid retention) ‘and in this she persisted to the last’.

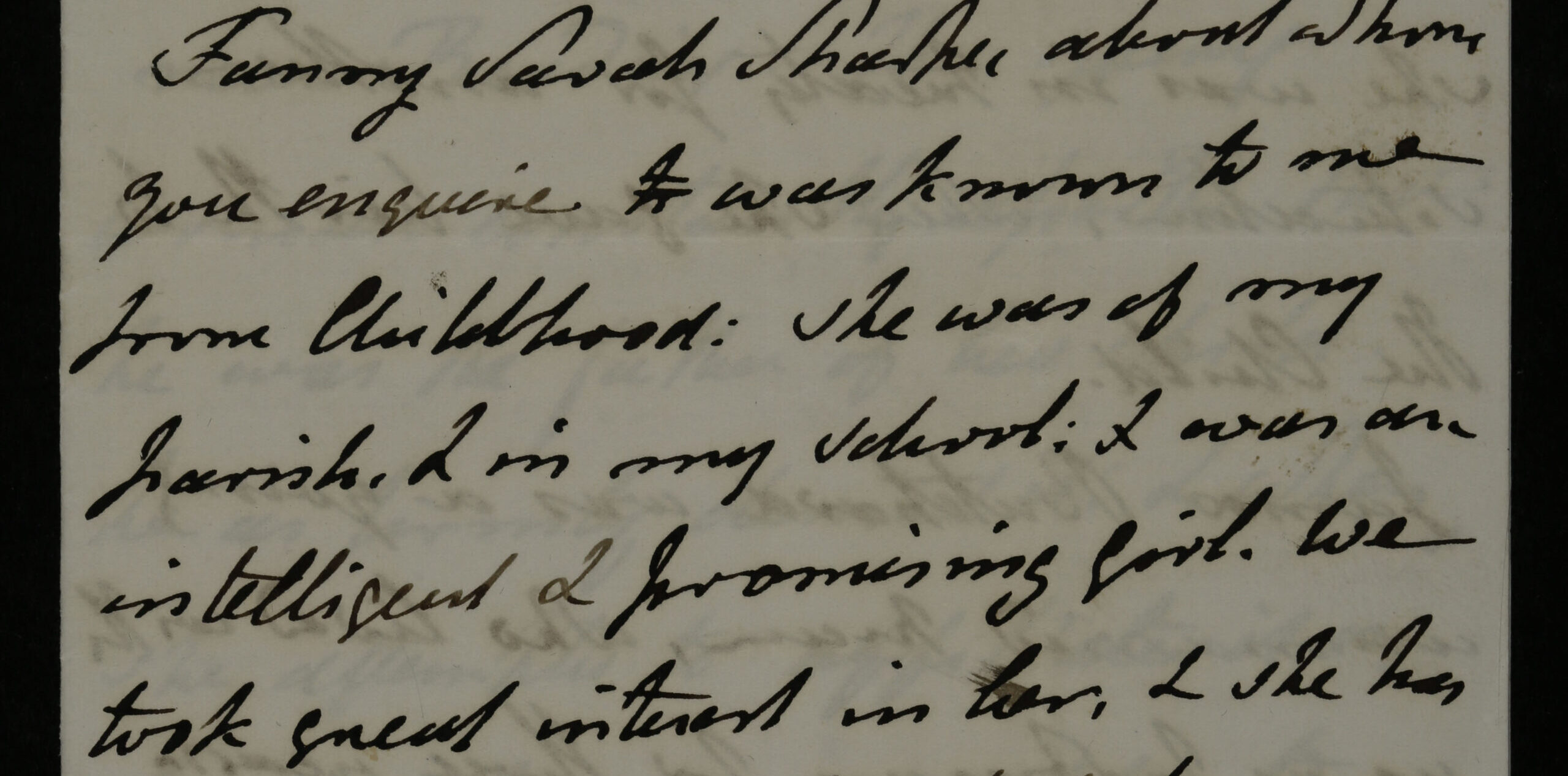

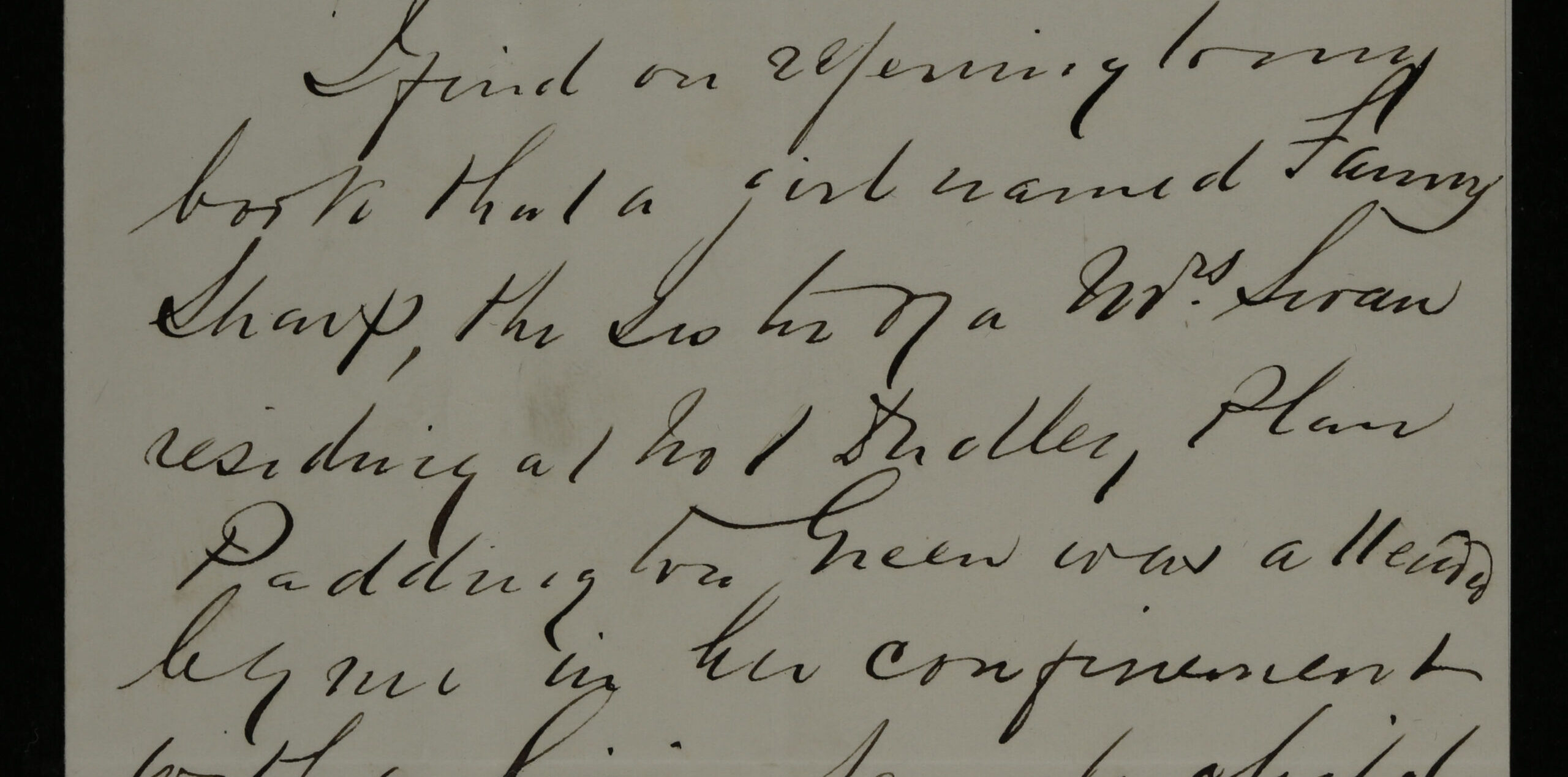

Austen-Leigh’s letter

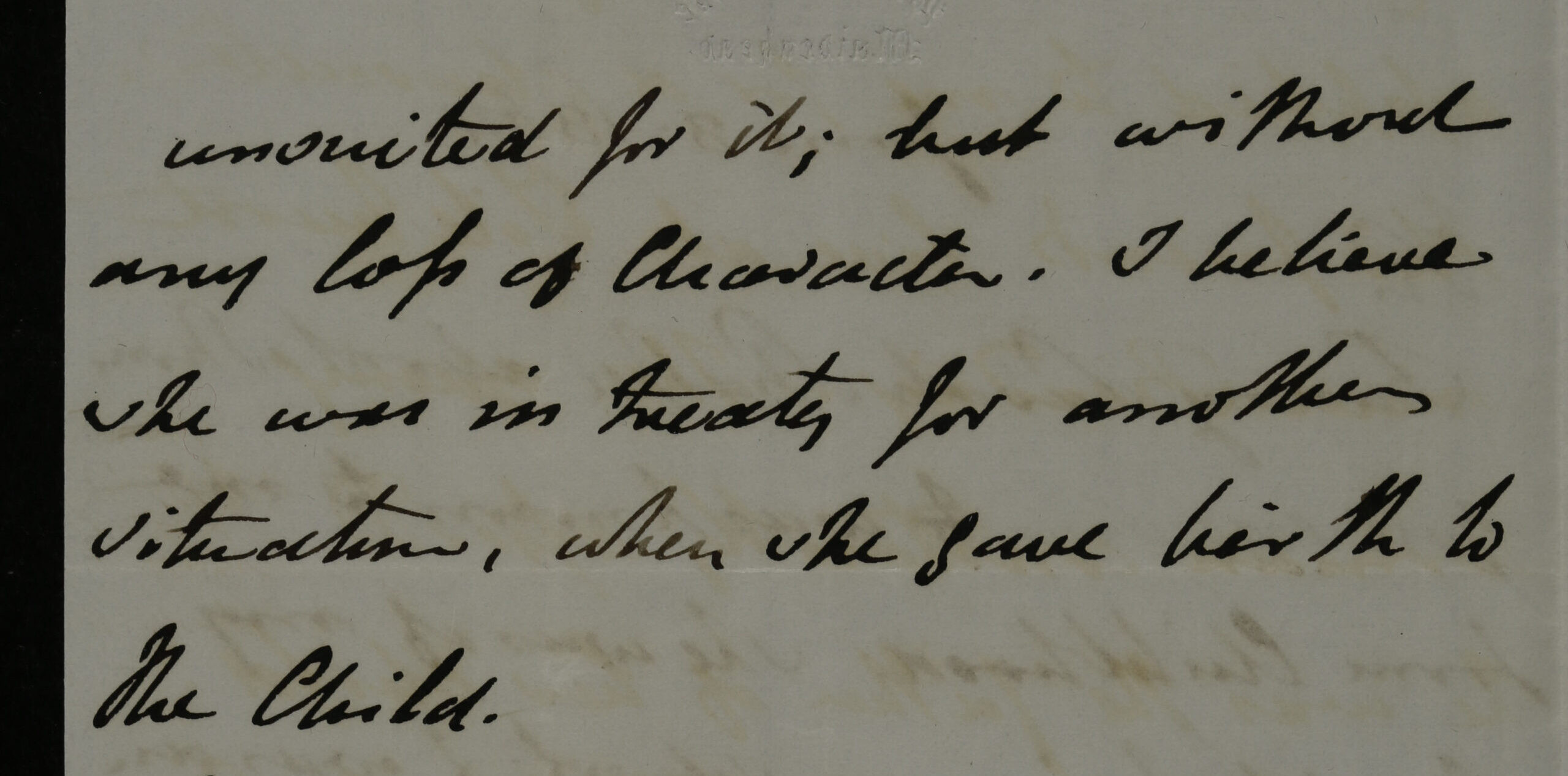

For his part, Austen-Leigh was under the impression that Sharp had left the Lingwoods ‘because she was unsuited for it; but without any loss of character’.

In his letter, dated 8 June, Austen-Leigh explained that Sharp had been ‘known to me from childhood. She was of my parish & in my school; & was an intelligent & promising girl. We took great interest in her & she has received much friendship from my family.’

Butchard had left the vicarage in April, but ‘not in consequence of this charge’. Austen-Leigh had known of Butchard’s plans to go into a different line of work, but did not know his current whereabouts.

The tone and content of Austen-Leigh’s letter are remarkable for their lack of moral judgement on Sharp. He attempts to present the facts of the case logically:

‘The young woman constantly asserted that he was the father of her child: he as firmly denied it; & when she attempted to affiliate it on him, she was unable to bring forward any confirmatory circumstances & failed in the attempt.

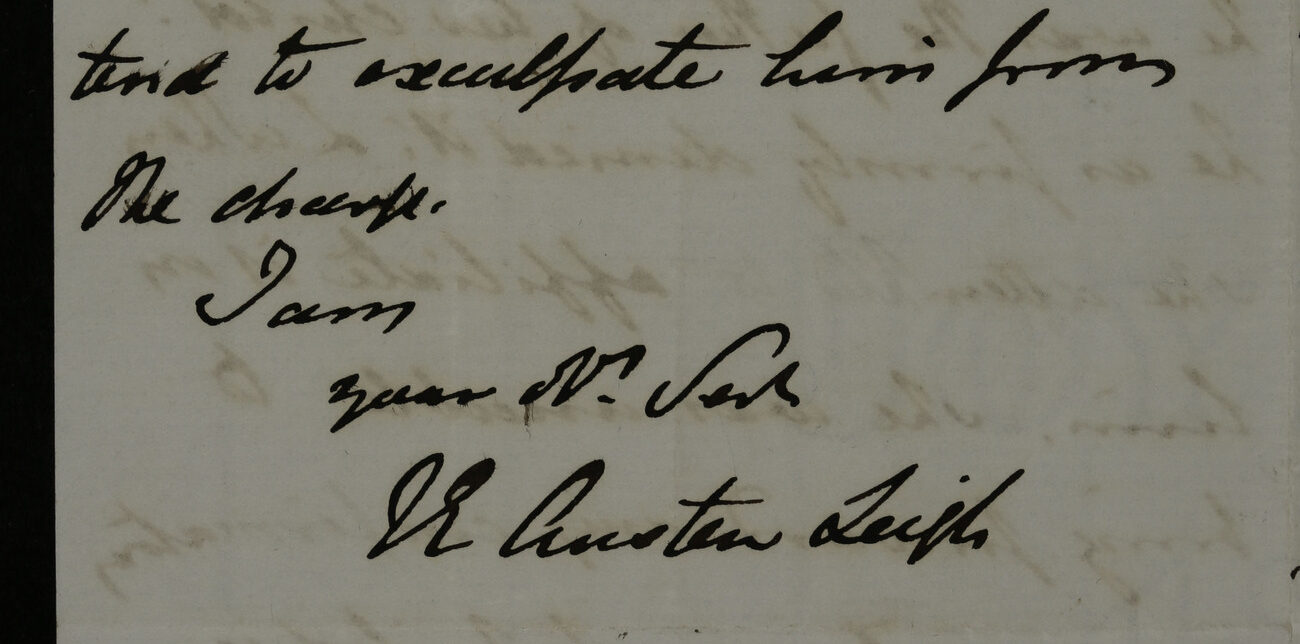

‘This is all that I can tell you. The affair has caused us much distress & perplexity; nor can we arrive at any conclusion which perfectly satisfies our judgment. There are some circumstances which seem to criminate & some which tend to exculpate him from the charge.’

As vicar, Austen-Leigh should have been the moral pillar of his community. This episode is likely to have caused him embarrassment, to say the least, because both the Lingwoods and the Buckleys knew of it. Unfortunately, the Hampshire Archives’ run of Austen-Leigh’s diaries does not include those for 1863 and 1864, and so, it is not possible to glean further insights.

Subsequent events

On 14 June 1864, the Foundling Hospital admitted Sharp’s daughter and gave her a new name, Mary Mead, and the number 21035. Mary was sent to a nurse in the countryside, where she died on 17 September, aged seven months.

Five years later, on 5 December 1869, Fanny Sarah Sharp married Private Henry Pritchard of the Fusilier Guards. They went on to have three children, two girls and a boy. And on 16 December 1869, Austen-Leigh published the first edition of his memoir of his famous aunt. The original print run of A Memoir of Jane Austen – 1,000 copies, dated 1870 – quickly sold out.

You can view a gallery of images of the letters and documents below. Click on the images to expand the documents.