Coram’s Foundling Hospital Archive contains hundreds of thousands of documents, a quarter of which have been digitised and transcribed in the Voices Through Time: The Story of Care programme. My role as Heritage Engagement Intern has given me the opportunity to delve into these records and uncover the stories hidden within. The discussions they can spark make the archive feel incredibly exciting and relevant today.

Discovering lives

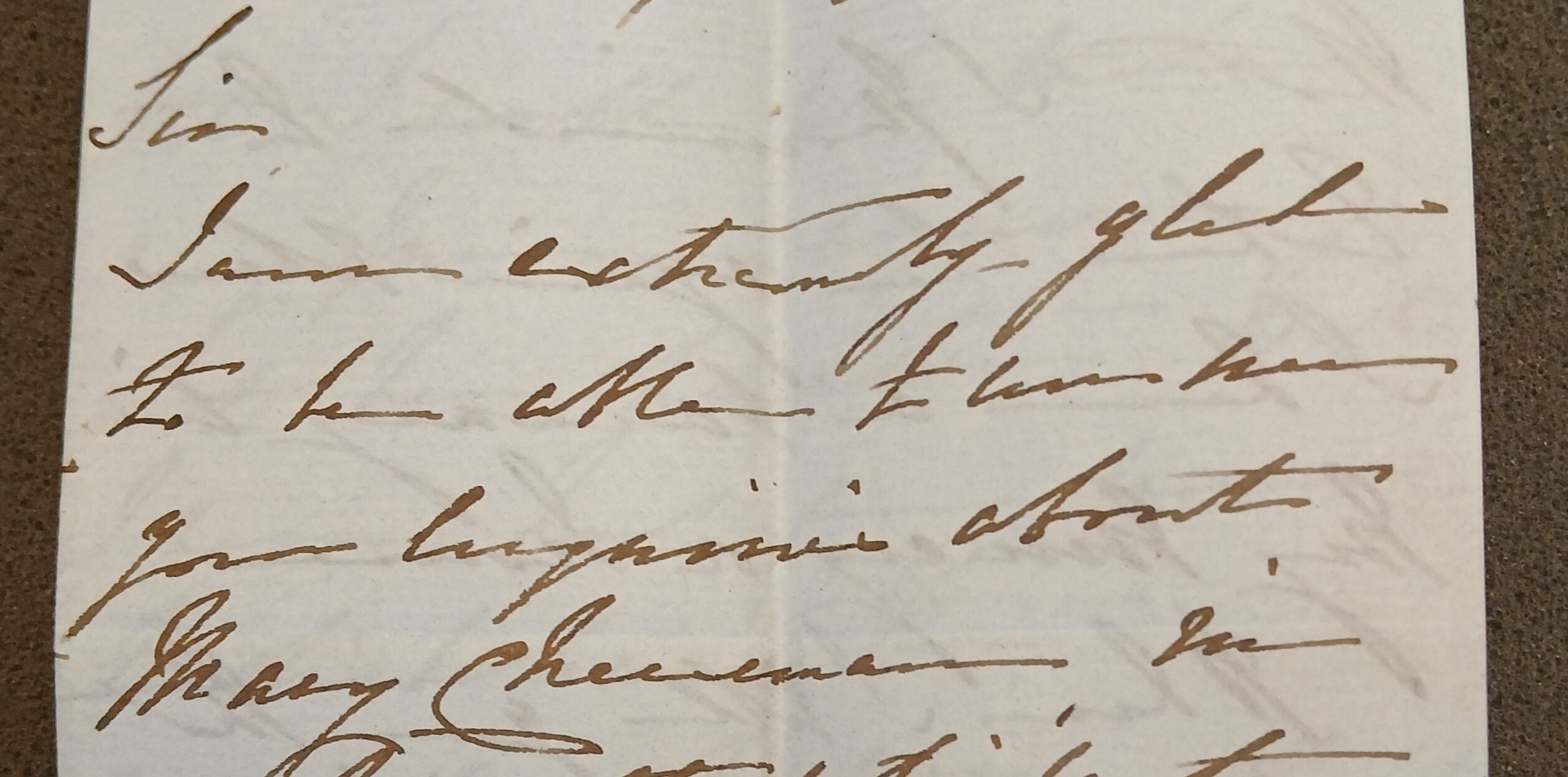

One of the most exciting aspects of my role is the remarkable stories I encounter every day in the digital archive. At times surprising, poignant, and challenging, many of these might remain hidden if these documents had not been digitised. While working on transcriptions of mothers’ petitions, I came across a report that had been missed in the transcription process. As I transcribed it, I discovered that it contained a copy of a letter from Catherine Dickens, the wife of author Charles Dickens. She was writing to encourage the Foundling Hospital to accept the illegitimate child of her former wet-nurse.

In the coming weeks I would uncover the mother’s story and trace her child, Ellen Waters, to Italy. I widened my search to the physical archive held at The London Archives, which includes correspondence from Ellen and her employers. Excitingly, I was even able to handle the original letter from Catherine Dickens.

Each discovery sparked new avenues to investigate: by looking into the family she worked for, I found that she was linked to another literary figure, Edward Lear. His personal diaries, which were digitised by Harvard University, then revealed the details of her later life. She was living in Italy in the period of the country’s unification, so finding government documents like birth or death certificates was difficult. Newspaper archives confirmed some details of the story. Bringing all of these snippets from archival documents together – many of which meant very little by themselves – was like piecing together a huge, satisfying jigsaw puzzle.

Studying for an undergraduate history degree during the pandemic meant that I had very little hands-on experience with primary research. This was the first time I had the opportunity to uncover, research, and write about a piece of history that no one else knew about, which was such a rewarding process. It is really exciting that through my work on the online digital archive, countless other stories like this will be uncovered by people all over the world.

Reflecting on gender

During my degree, I was especially interested in studying gender and women’s history. I feel slightly spoiled by the wealth of information and experiences contained within Coram’s Foundling Hospital Archive. Mothers’ petitions reveal personal stories of relationships, sex, consent, motherhood, and so much more.

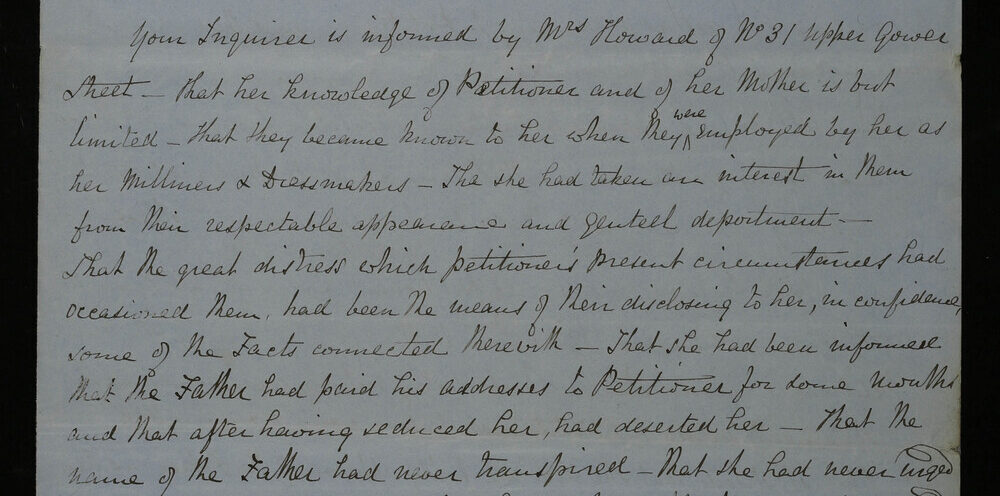

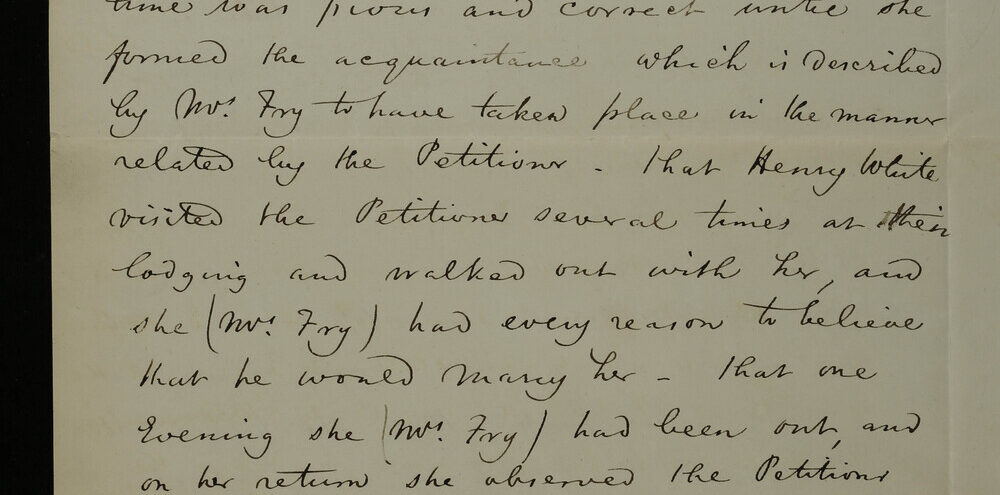

The language used to discuss sex and relationships is particularly interesting to me. Mothers referred to the fathers of their children ‘seducing them’, ‘paying them attention’, ‘walking out with them’, and having ‘Criminal Conversations’ – all euphemistic ways of referring to romantic and sexual relationships. To have records in which women openly discuss these topics is rare, and it is fascinating (and frustrating!) to consider that these terms would have had particular connotations that have been lost to time. For instance, in the 19th century ‘seduction’ was defined as ‘the act or crime of persuading a female to surrender her chastity’. The term is used more generally in the petition records, however. It could denote a range of sexual encounters, including consensual sex, sexual assault, and rape.

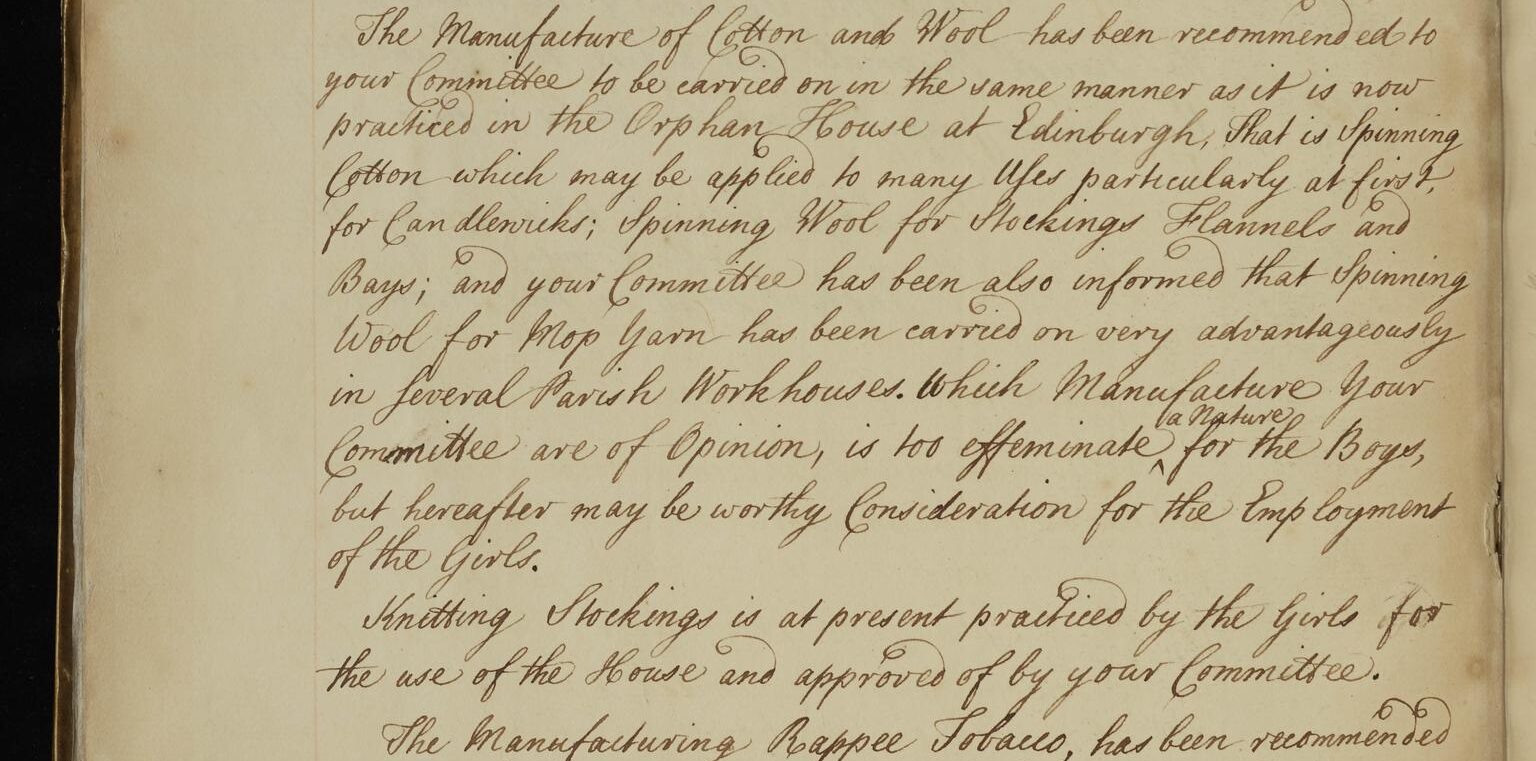

I have discovered nuances and contradictions in how boys and girls were treated at the Foundling Hospital. While researching how Foundlings were taught to make and mend clothes, I found a passage in the Sub-Committee minutes which discussed the ‘effeminate’ nature of spinning wool. Therefore, only girls learned to spin. However, boys carried out work that might now be considered similarly gendered, like darning, mending, and knitting. While girls had a narrow range of employment opportunities upon leaving the Hospital (usually going into domestic service), they also learnt to read and write. This level of education was inaccessible to other lower-class women and was progressive for the time. Nuances and contradictions like these have probably complicated my ideas about gender in this period as much as they have clarified them!

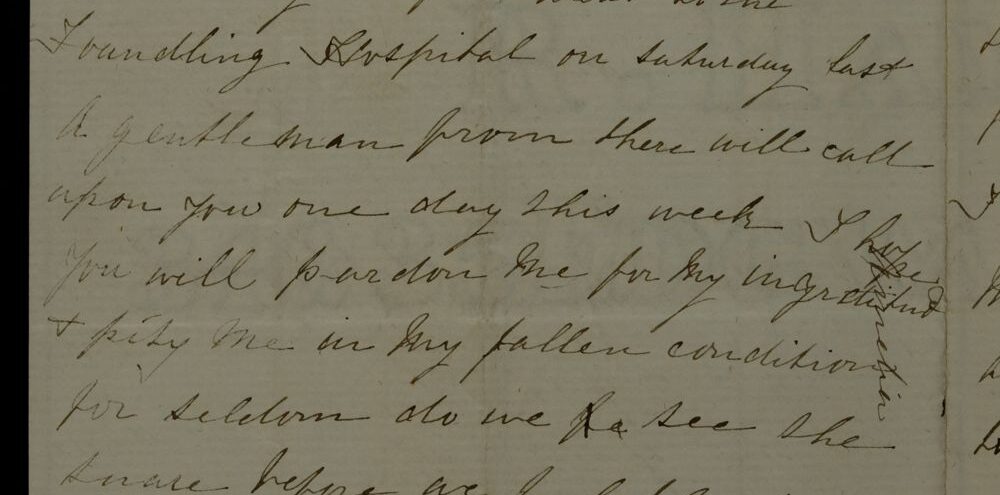

Nonetheless, it is a privilege to be able to work with an archive which holds records of women who are otherwise unrecorded. Poor, single mothers have been subjected to generalisation and judgement throughout history. To read their stories in their own words feels incredibly poignant and humanising, and is one of many reasons that the archive remains relevant to this day. One phrase that has stuck with me comes from a mother who had been ‘seduced… against [her] wish’. She wrote to her sister:

‘Pity me in my fallen condition, for seldom do we see the snare before we feel the smart’.

Connections to music

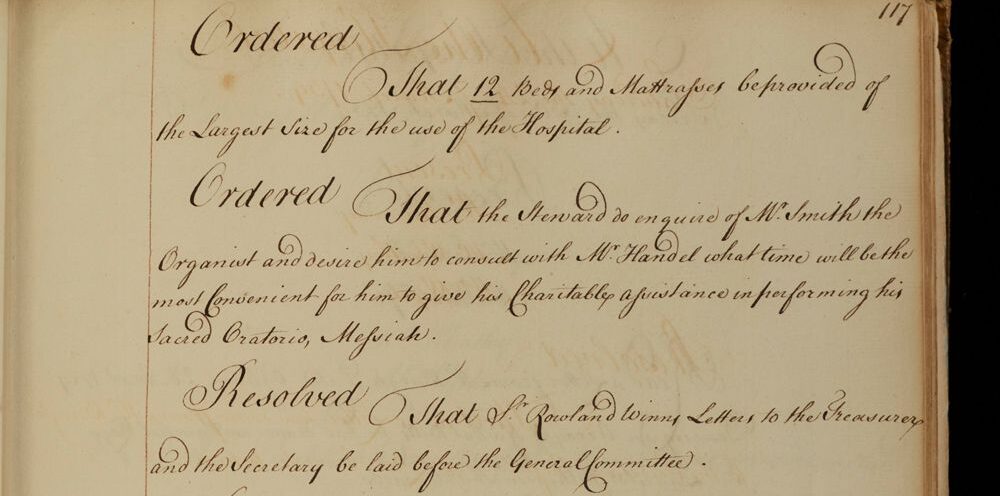

Outside of work, I play the trombone and have a love of music and the arts. As part of this internship, I undertook a placement at the Foundling Museum where I worked with the librarians of the Gerald Coke Handel Collection. I learnt more about Handel’s links to the Foundling Hospital and got up close with original scores, programmes and the will of the famous composer – a music nerd’s dream!

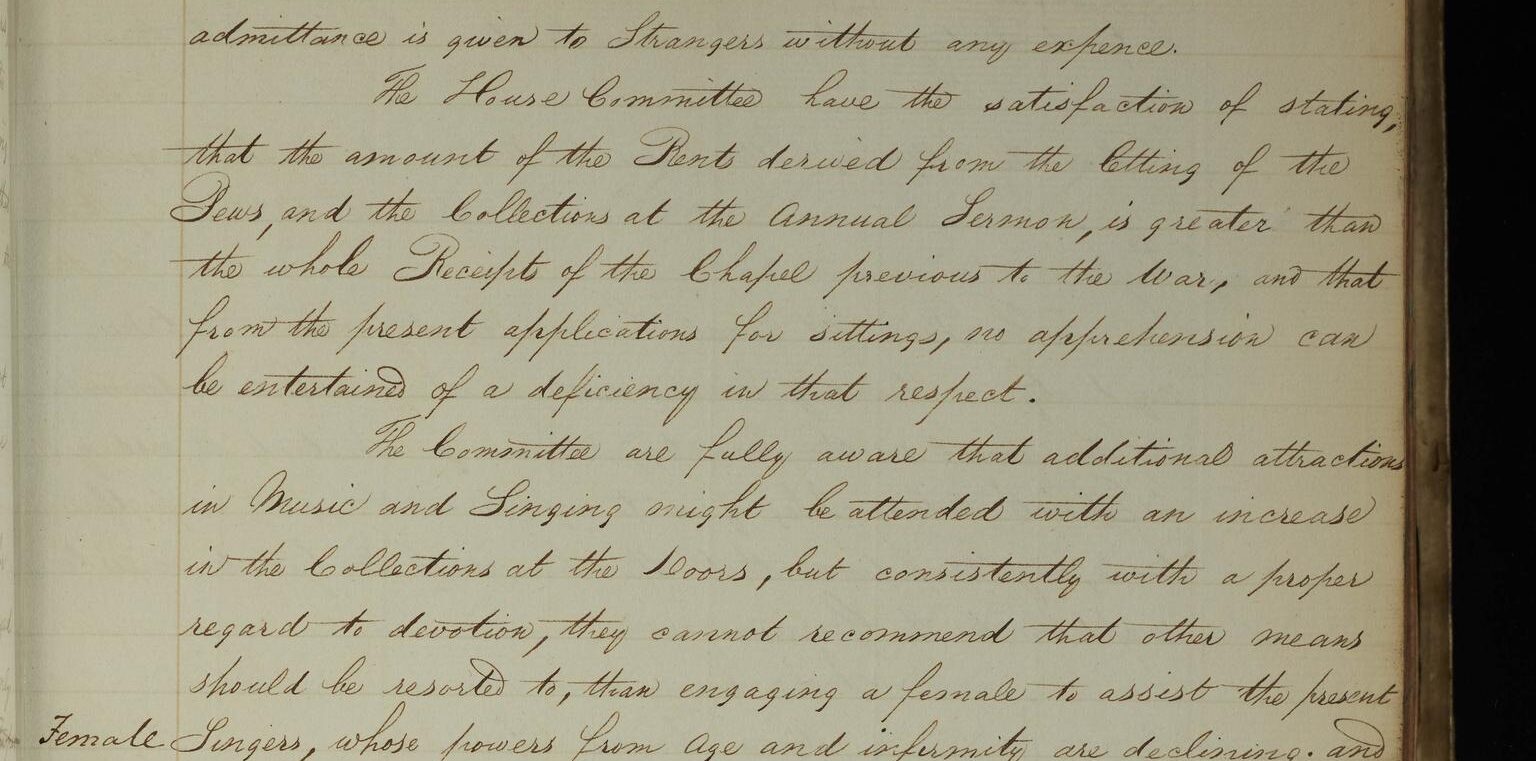

At a Coram Society event about music within the charity, it was lovely to hear former pupil John Caldicott talk about the value of music for children at the Foundling Hospital, both singing in the chapel and playing in the band. Having played in orchestras and brass bands throughout my childhood, I really connected to this. Music would have had social and emotional benefits for Foundlings, even if Hospital staff viewed it as an opportunity to raise money and provide religious education.

This sense of connection is one of the most remarkable things about the Foundling Hospital Archive. As I learned in researching an article about the tokens, these records may be bureaucratic in nature, but so much emotion and humanity lies within them that cries out to be explored. Add to this the wealth of information about women’s experiences, childcare, disability, education and more, and it feels all the more exciting that my work has helped to make the archive accessible to the public.

Copyright © Coram. Coram licenses the text of this article under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 (CC BY-NC).