Our fantastic conservators are busy in our archives, restoring our precious artefacts so that they can be digitised for future generations. This blog series explores the finer detail of their work, in their own words.

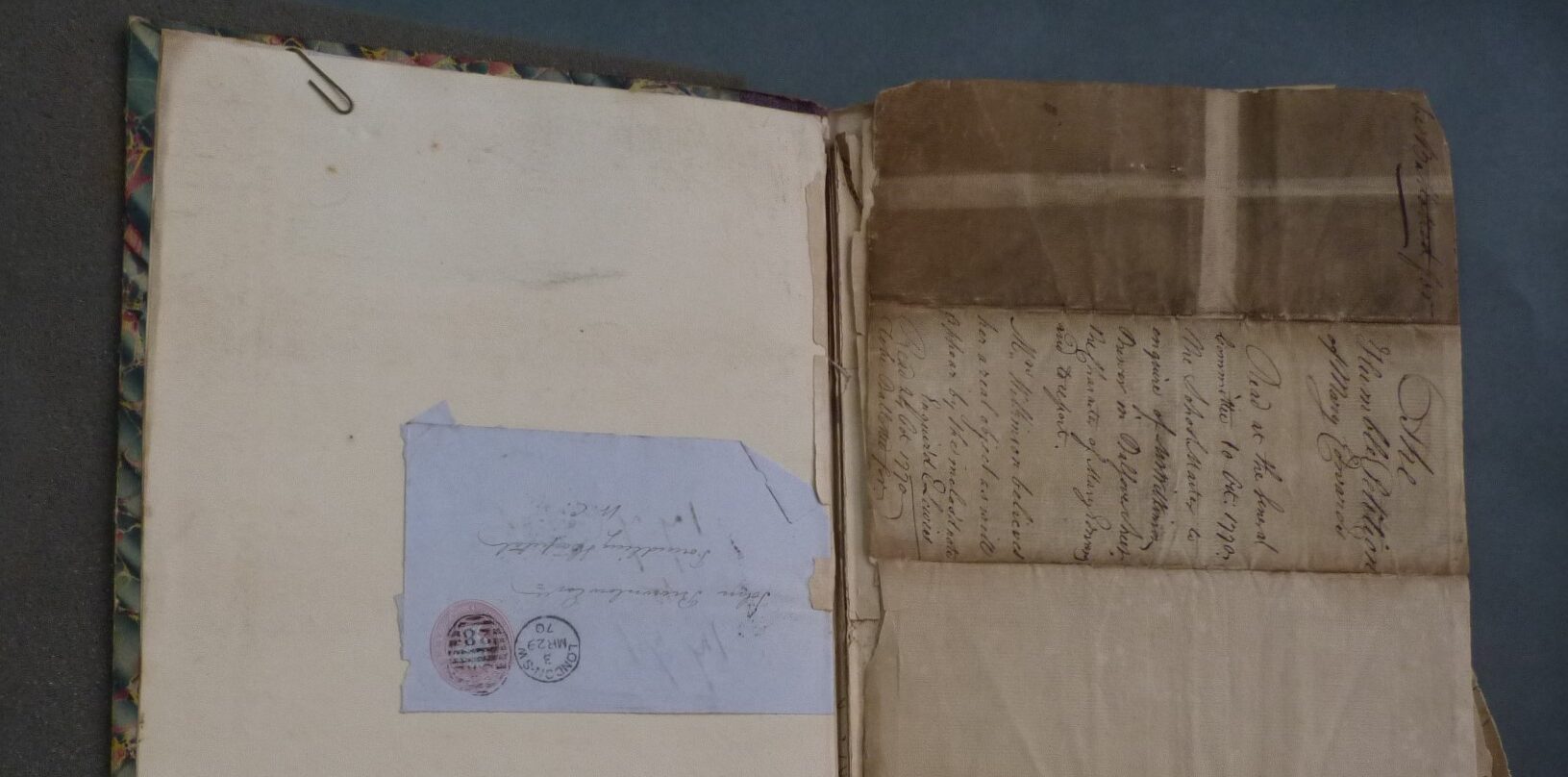

The items I am conserving are petition letters asking to admit children to the Foundling Hospital from 1768 – 1800; the letters were bound into 25 volumes in the early 19th Century. The way they have been bound is causing damage to the letters and they need to be separated and repaired before they can be handled for digitisation.

I cannot help but be excited about being part of this project. Petition letters contain such personal stories and it is both terrific and terrifying to know the work I do will ensure others are able to read and relate to those writing 250 years ago. Working with physical items always implies surprises and unanticipated challenges. I have had to adjust my treatment plan several times in the past two months as I have become familiar with the peculiarities of these books and their contents.

Conserving delicate documents

The letters were written on a wide array of papers – thick, thin, big, small, strong and weak – that have been sewn and glued together before attaching boards and a cover. As the larger papers protrude from the boards and the weaker papers were pulled by thread and glue, many are torn, creased and folded, and cannot be safely handled. The glue is causing significant damage, as it has seeped into the edges of the paper and dried solid, making its removal a risk of further damage. To pull apart the letters safely I had to remove the glue and in order to do so I had to soften it by applying a 6% methylcellulose poultice and 75% isopropanol.

This procedure allowed me to ease the letters apart with a rounded spatula. Once separated, it was much easier to repair them and I was able to understand how many separate sheets the volume was made of.

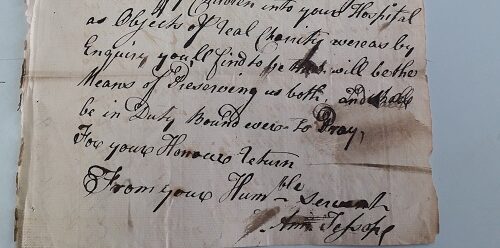

All the letters were once sent through the post and still carry evidence of their journey. In the 18th Century letters were written on paper that was folded up and sealed with wax or a cloth tie. These have been unfolded but there was ingrained dirt marking the original creases. Most retain proof of the original red or black wax seal, and there are even a few hand-stamped post marks. I cleaned each letter with chemical sponges that quickly blackened from the dirt.

A glimpse into the past

Looking through the letters, there are additional documents, like character testimonies, notes from those verifying the petitioners’ stories, and lists of the children admitted. These were sewn in with the rest of the letters or attached to them with metal pins, paper clips, glue, or circles of wax. The metal pins and paper clips tend to corrode overtime, so they need to be removed. The glue and pieces of wax are stable, but some were obscuring the text and it was a tough decision whether to keep the original attachment or remove it to uncover the hidden text. These loose additional documents were reattached to the letters with folded hinges of thin Japanese tissue paper adhered with a reversible starch paste adhesive to retain the relationship between them. The original metal pins, papers clips and boards are all kept together as a record of how the letters have been stored for 200 years.

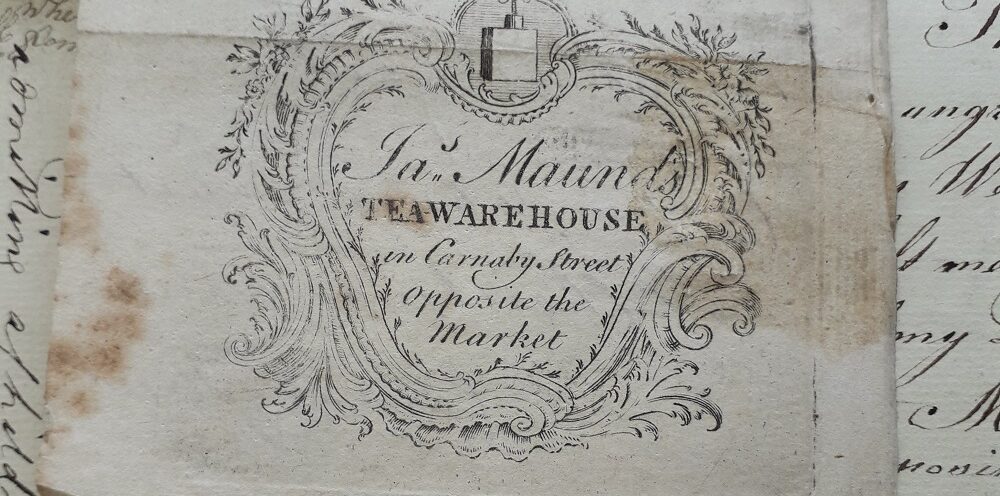

With each volume I have found a rhythm to the work and it has become easier to finish the repairs. However, some of the stories I happen to read while repairing the documents do make me pause. There are letters written by professionals that are signed with a shaky cross by an illiterate person. One letter looked like it was tear-stained. A few notes had advertisements or letterheads that suggest where someone lived or worked. There is not really time to sit and read them but, once they are all digitised, maybe I can join those volunteering to transcribe the whole collection.