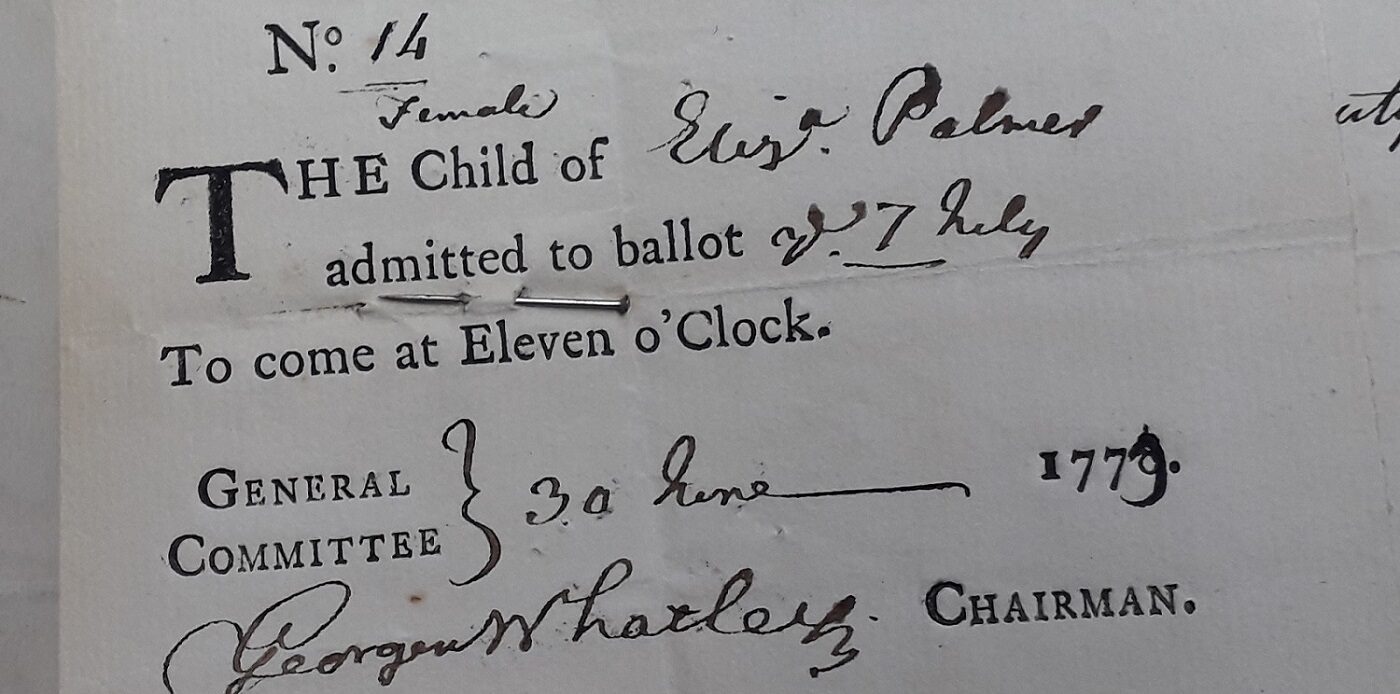

In the 18th century, thousands of people wrote petition letters to the Foundling Hospital governors pleading to admit their child into the institution. The petitioners would be reviewed to assess if their claims were accurate and, if they were deemed ‘a true object of charity’, they would be instructed to come to the Hospital on a set day and time.

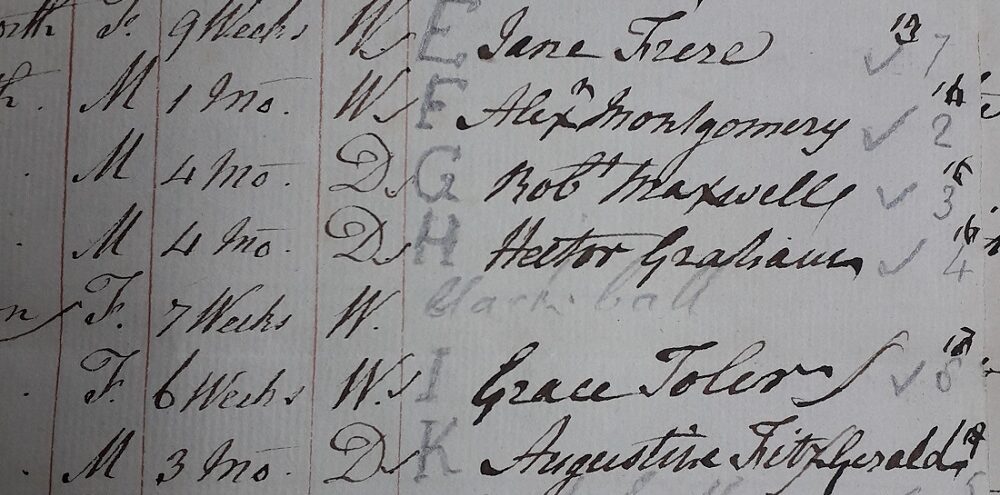

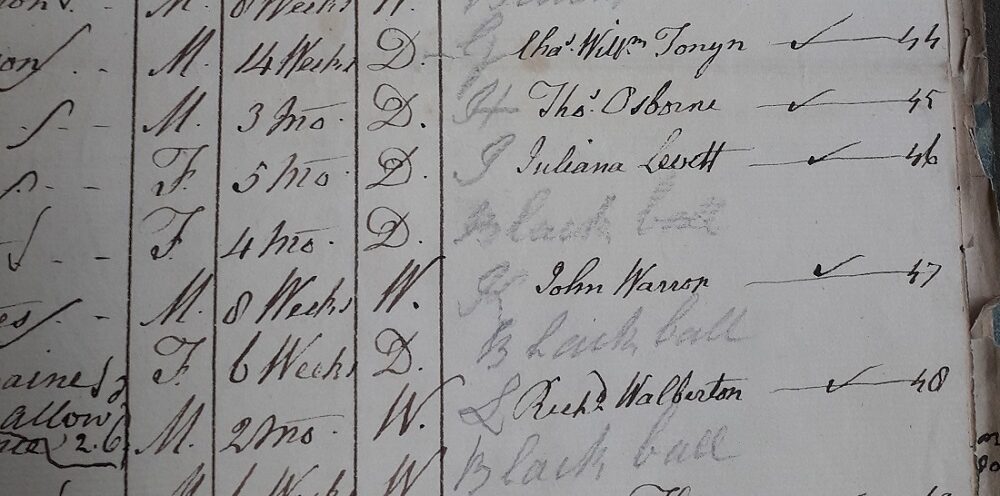

Acceptance of your petition did not guarantee your child admission to the Foundling Hospital. Places were limited and it was in such demand that the governors imposed a lottery, or ballot, in 1742. Mothers drew a coloured ball from a bag. A white ball meant that, so long as the child was healthy, they would be admitted. A red ball meant the child was put on the waiting list for admission. And a black ball meant the child was rejected. The proportion of black to red or white was occasionally adjusted depending on the number of available places. The clerk would record the number of those invited to the ballot, the name of the month, the gender and age of the child and whether they required a wet nurse. Then the lottery was drawn and they only recorded the names of the healthy children who were to be accepted into their care.

This lottery was in an open space with charged admission for viewing by the general public. It was often seen as a form of entertainment for patrons of the Hospital and ‘polite members of society,’ and some gentry wrote in their diaries about the crying women and babies, both those who were admitted and those who were ‘blackballed.’