Content warning: This article contains reference to sexual assault which individuals may find distressing. Find more information on our help and support signposting page.

Stories of Interest volunteer, Lauren Fernandes, explores the story of Agnes Hammond, a Foundling pupil who emigrated to Australia.

The Stories of Interest volunteers have been researching the little-known themes and connections between pupils at the Foundling Hospital to tell new and fascinating stories.

Agnes’s mother

For working-class women in nineteenth century Britain, opportunities were limited. Yet while she suffered her own hardships in her apprenticeships, Agnes Hammond’s placement in the care of the Foundling Hospital provided her with unique possibilities, both in terms of work and travel.

Agnes Hammond was born on 27 November 1815 and admitted to the Foundling Hospital on 6 April the following year. She was baptised on 17 April 1816 by John Hewlett, the Morning Preacher at the Hospital’s chapel. Due to the number of children who went through the Hospital, children were assigned numbers. Agnes’s was 19172.

Williamza White was 25 years old and unmarried when she had Agnes. She was living as a Lady’s maid with the Montase family at 2 Marylebone Lane in Portman Top, London. Williamza had travelled with them to Florence, Italy, in August 1814, where she met John Cliffe Esq., a Gentleman who knew the family.

According to the account in her petition letter, when the family had gone to Rome, so too had John, who stayed at an adjoining hotel and ‘seduced’* Williamza on 17 March. The family then went to Naples and did not return to Rome as planned, after which Williamza did not see or hear from John again.

A Lady named Amelia Angerstein gave a character reference in support of Williamza, stating that she had known her since childhood and only lost sight of her at ‘the unfortunate time when she went abroad.’ Amelia was ‘thoroughly persuaded’ of her good character from both her personal ties with Williamza and the respectability of the Montases.

Sadly, Williamza’s experience was common as a maid with few rights. Her daughter Agnes at least grew up in a secure environment at the Foundling Hospital. She gained an education, which was rare for girls at that time, and did not have to seek work opportunities herself or go into a workhouse. Agnes had support from the Foundling Hospital to fall back on, rather than face homelessness, should her employment end. Ultimately, though, she still faced a life not so different from her mother’s, in working as a maid.

One apprenticeship after another

Foundlings were apprenticed from the year they turned 16, usually staying in the same position until they left the Foundling Hospital’s care upon turning 21. Agnes, however, faced problems in her placements, resulting in multiple apprenticeships.

While none of the Foundling children went into lucrative apprenticeships, the girls were much more limited in their prospects because they all were apprenticed in ‘household business’, i.e. as domestic servants. In contrast, the boys had a more varied range of occupations, being trained in an actual trade.

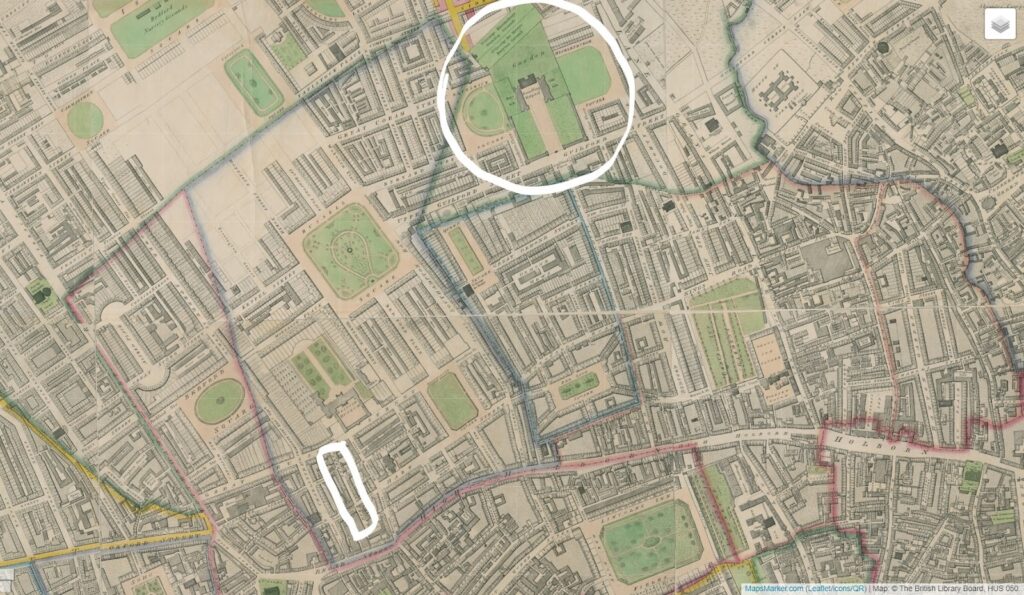

Map shows Foundling Hospital (top) and address of George Hankin (bottom left) in Bloomsbury, 1819

Agnes’s first apprenticeship began on 18 April 1831 and was due to expire on 25 January 1837. She was to be instructed in household business in the house of George Hankin, whose occupation was listed as ‘Gentleman’. Mr Hankin lived at 29 Duke Street, not far from the Foundling Hospital (see map). Both were in Bloomsbury, an area that looked very different to how it does today; it was much more rural, sitting on the outskirts of London.

Agnes’s apprenticeship with Mr Hankin ended in October 1832, after she had been ‘subjected to conduct from a male relation in the family’. The Matron of the Foundling Hospital, therefore, advised that she should be moved to another placement for her own welfare, which the Hospital Sub-Committee supported.

Agnes’s second apprenticeship, again in household business, ended for behavioural reasons. She was described as ‘idle, obstinate, insolent, and indecent in her conduct’, prompting the mistress of the house, Mrs Arnell, to request her termination. Mr Arnell’s occupation was listed as ‘Gentleman’, and the couple lived at 15 Clark Street in the parish of Mile End. Agnes left this position in April 1833 after being reprimanded for her behaviour.

Notes on the terminated apprenticeships of young girls often put this down to issues with their behaviour, which led to their return to the Hospital upon the request of their employers. Given the treatment and view of women and girls in this period of history, we might not take the same view today about their behaviour and actions.

After a third failed apprenticeship, the Matron found a trial placement with a view to apprenticeship with Miss Ruscoe in June 1833. This also ended poorly, resulting in Agnes’s return to the Hospital in September 1833 and her subsequent placement in the care of Henry Grammar, the Beadle of the Foundling Hospital chapel.

Another apprenticeship was found in September 1833, but Agnes stayed there for only seven months before she returned once again to the Hospital in April 1834. The Secretary of the Sub-Committee then applied to the Lady Patronesses of the Victoria Asylum in Chiswick, where Agnes was to be held for a ‘limited time.’

Emigration to Australia

Whether this was by her own request or at the instruction of the Hospital, as was usually the case, Agnes emigrated to Australia on 10 July 1834, at the age of 18. She sailed on the David Scott, one of several ships sailing from Gravesend, England to Sydney, Australia, taking single women to Australia. Agnes sailed with three other Foundling girls, Catherine Cameron, Prudence Gibbs, and Martha Smith. The ship arrived in Australia on 25 October 1834.

Sir William Curtis, 1st Baronet of Cullands Grove, personally inspected and approved the outfits prepared for them by the Matron. The girls were also all eligible for government assistance, meaning they did not have to pay the fare. They also received an allowance from the Foundling Hospital, as they would have remained in its care for another three years.

Information on what happened to Agnes after her arrival in Australia is hard to find, but records suggest that she may have married Gilbert Warren in 1841. Whether this was the same Agnes Hammond cannot be confirmed, but it is possible, given that the push for women to emigrate to Australia from Britain and Ireland was to become wives for the disproportionate population of men at the time.

*The word ‘seduced’ appears frequently in our archives, especially in petitions from mothers to the Foundling Hospital. From the 15th century onwards, its specific meaning in English was to entice a woman who had not been sexually active to have sex outside marriage (termed ‘criminal conversation’). The nearest equivalent today to its usage in those earlier times would be ‘grooming’ — although this is not an exact equivalent. Mothers applying to the Foundling Hospital made it clear to the governors that these were their circumstances, in order to have any chance of their children being admitted.

Today the word seduction is used far more broadly and does not carry the connotations it did in earlier centuries. Its usage in eighteenth and nineteenth century petitions from mothers to the Foundling Hospital point to the widest range of sexual encounters, including consensual sex, sexual assault, and rape.

Bibliography

British Library Cartographic Items Maps 33.e.24

NSW Pioneer Index – Pioneer Series, 1788-1888

Foundling Hospital Archive:

General Registers

A_FH_A_09_002_005_208

Baptism Registers

A_FH_A_14_004_001_531

A_FH_A_14_004_001_532

Apprenticeship Registers

A_FH_A_12_003_002_291

Sub-committee minutes

A_FH_A_03_005_034_035

A_FH_A_03_005_034_098

A_FH_A_03_005_034_099

A_FH_A_03_005_034_136

A_FH_A_03_005_034_162

A_FH_A_03_005_034_238

A_FH_A_03_005_034_262

A_FH_A_03_005_034_266

Petitions admitted

A_FH_A_08_001_002_025_014_b1

A_FH_A_08_001_002_025_014_b2

A_FH_A_08_001_002_025_014_c1

Copyright © Coram. Coram licenses the text of this article under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 (CC BY-NC).