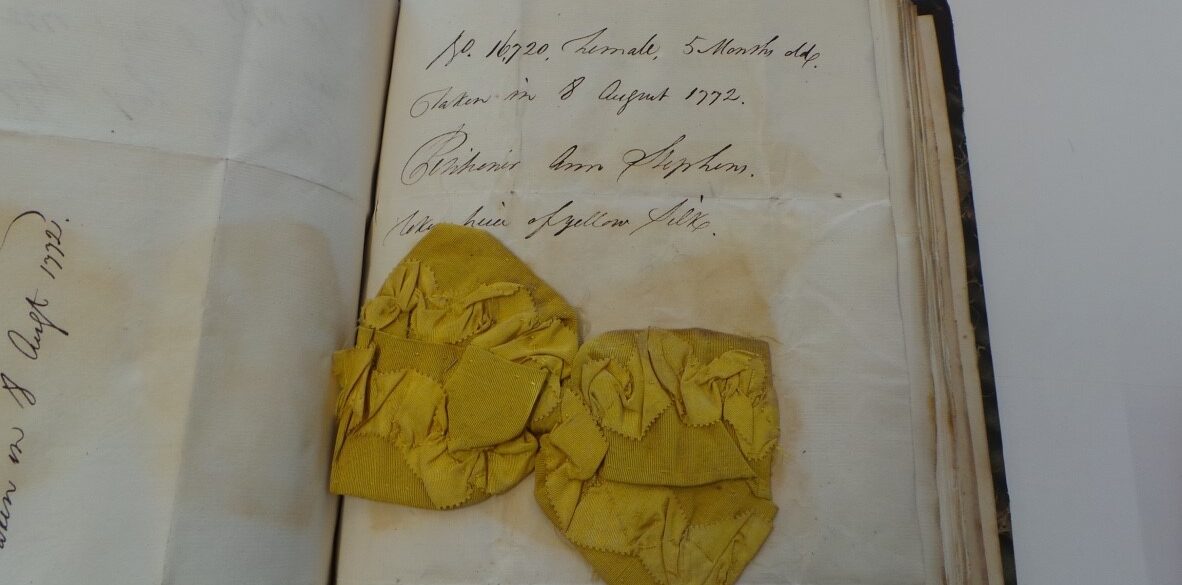

Some years ago while visiting London from my home in Western Australia, I read a newspaper article about the London Foundling Hospital. I had no prior knowledge of this extraordinary place with its sad history, but I teamed up with my lovely friend from when I was a secretary in London in the 1970s and we went together to visit the Foundling Museum. We were both fascinated and moved by the story of Coram, most particularly the display of Tokens so lovingly portraying the anguish of mothers who had left their children in the care of the Foundling Hospital.

Back in Australia and at the age of 65 I decided to enroll in an Arts Degree at the University of Western Australia and soon developed a love of early modern history, particularly social history, and even more fascinating, the History of Emotions. When it came to decide on a project for a research paper I looked for a topic which would help me discover the voices and emotions of ordinary people from the past who had left no documents themselves. With its history of changing circumstances for the acceptance of infants and meticulous record- keeping, it had to be the London Foundling Hospital!

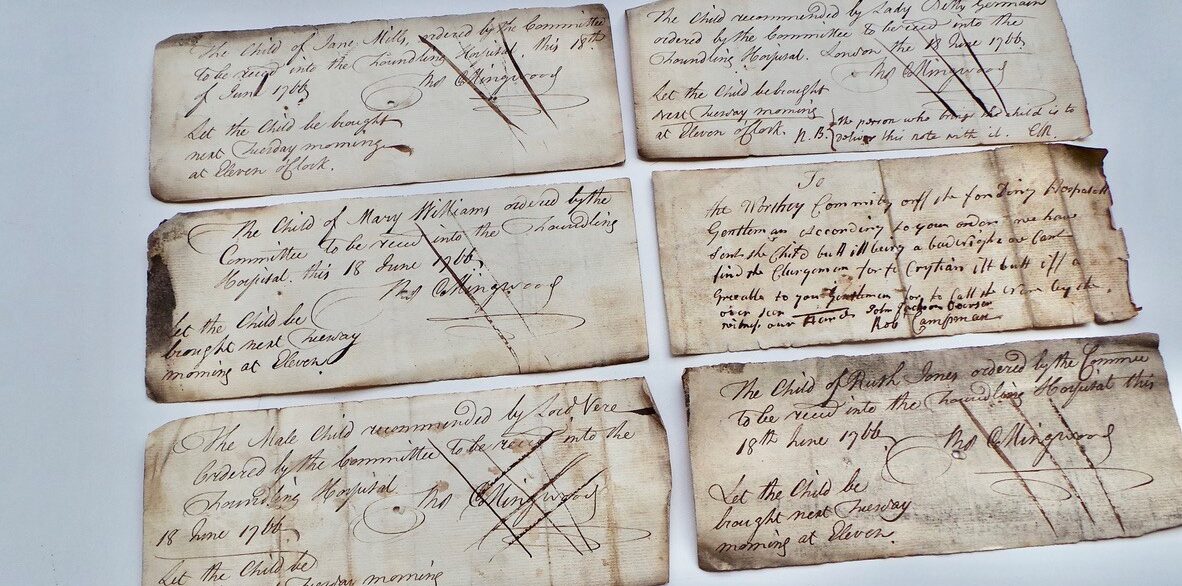

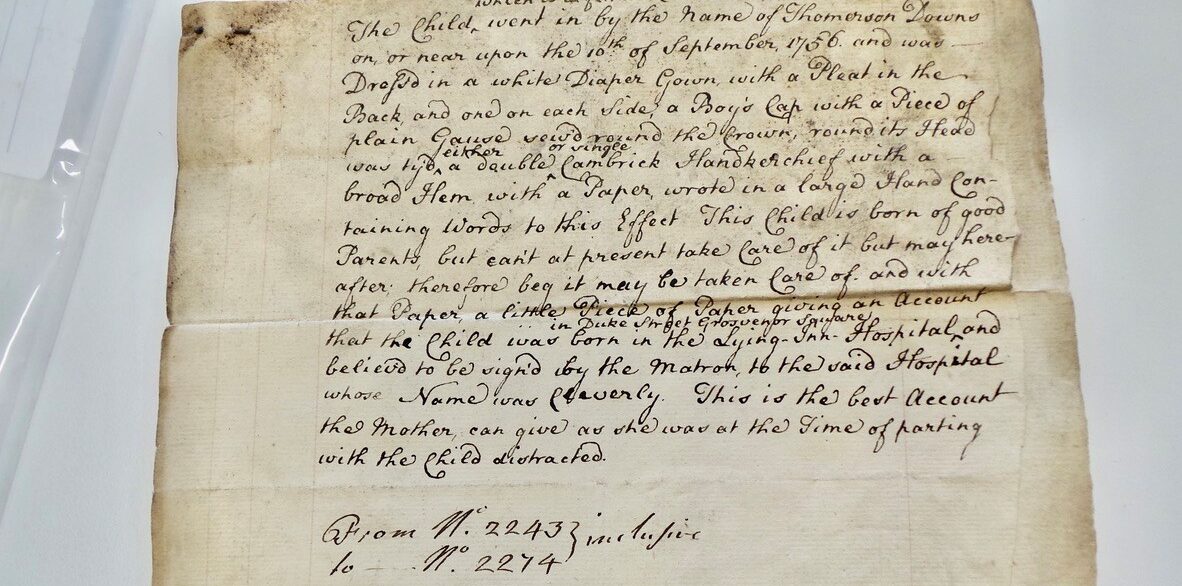

Emotions are usually expressed in what is spoken or written, but sometimes they can be teased out from what is left unsaid. I was keen to see petition letters (letters written on behalf of mothers to petition governors to admit their child) and billet books (inventory of items left with children upon admission) from the hospital. I found a book in the University Library on the correspondence of the Hospitals’ Berkshire Inspectors, all of which I hoped would contribute to the narrative that surrounded the Hospital in the eighteenth century.

The problem was that I lived on the other side of the world and these records were stored physically in the London Metropolitan Archives (LMA). Many are in a fragile condition and not available for researchers, especially an undergraduate such as me. However, In 2012 I was able to make another trip to the UK and planned to visit the LMA. I had applied for a History card and had a list of records I hoped to see. In reality I had no idea of how to request items or what to expect, but with gracious help from the archive assistants I found my first request had been processed and I was next in line to receive my first bundle of documents. I imagined they would be photocopies and some transcribed letters, so I was not prepared to receive a box of original documents.

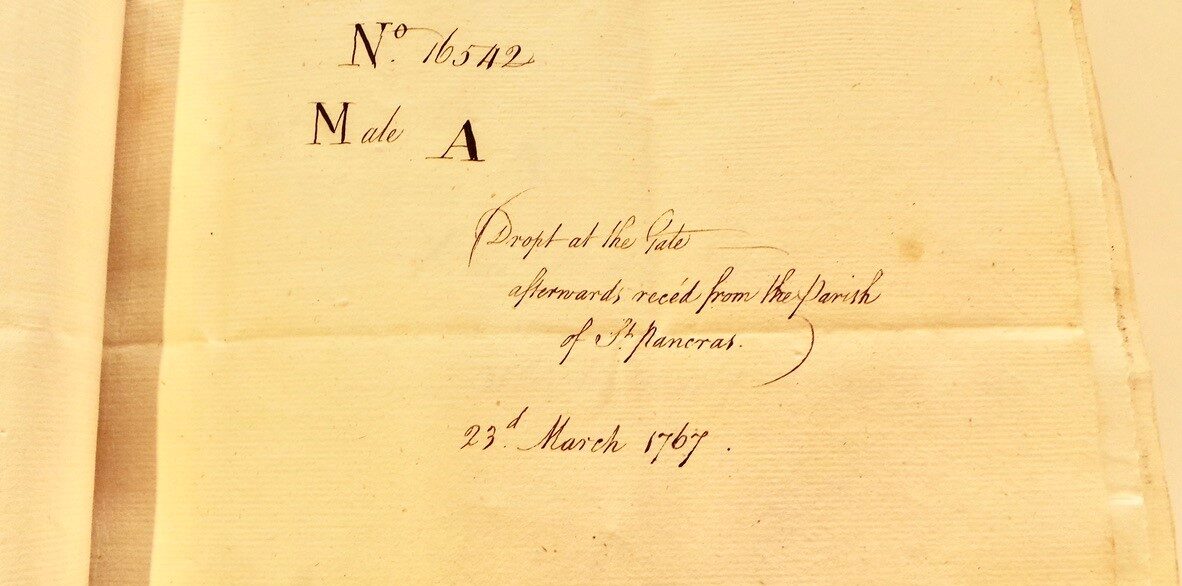

Even just looking at these handwritten and poignant notes was an emotional experience which I have never forgotten. Even then it confirmed a complex set of unspoken emotions which surrounded every abandoned child. I was also immediately convinced that these precious artefacts must be preserved at all costs. I am delighted that the Voices Through Time project is now working to digitise the archives, so that researchers like me don’t have to fly around the world to access these incredible items.

I found that there was a language of emotion both spoken and unspoken that surrounded the hospital in the eighteenth century. The narratives were not only about the children who were ‘dropt’ at the Hospital and the physical evidence of the tokens they left behind, but also they were about those who had the responsibility of continuing to look after them such as the country midwives and the Berkshire Inspectors whose correspondence revealed feelings of attachment to the children in their charge and sadness at the high level of mortality which they experienced.

Below you can explore some of my findings in more detail.