Content Warning: This article contains references to physical abuse, which readers may find distressing. Find more information on Coram’s help and support signposting page.

Thomas Waugh’s story challenges the misconception that Foundlings did not have familial relationships, and highlights a trend in the 18th century of children running back to their childhood nurses. It is also a sombre reminder of the struggles that they could face as apprentices– unhappiness, neglect, and abuse.

Early life

Thomas Waugh was admitted to the Foundling Hospital on 15 September 1758. He was one of 14,934 children who arrived during the General Reception. During this four-year period (1756-1760), Parliament financially supported the Hospital on the condition that it accepted every baby brought to its door (Bright, 2017).

Thomas was baptised in the Hospital chapel, and assigned the number 9853. Shortly after, he was sent to be wet nursed by Elizabeth Taylor in Sandridge, Hertfordshire. He remained here for eight years before returning to the Founding Hospital on 3 October 1766. At a later date, he returned to her care, and stayed there until 10 January 1769. It is likely that Thomas was sent to the countryside to improve his health, which reflected the contemporary belief that fresh air could cure ailments (Berry, 2019).

Apprenticeship and elopement

On 10 May 1769, aged 10, Thomas was apprenticed to William Bradbury, a glazier who worked on Lawrence Lane, London. The Foundling Hospital paid Bradbury a fee of £3 – an incentive to take on a Foundling as an apprentice. The British Government continued to provide grants to cover the costs of the children admitted during the General Reception, with the provision that a certain portion of the funding was for apprenticeship fees (Bright, 2017).

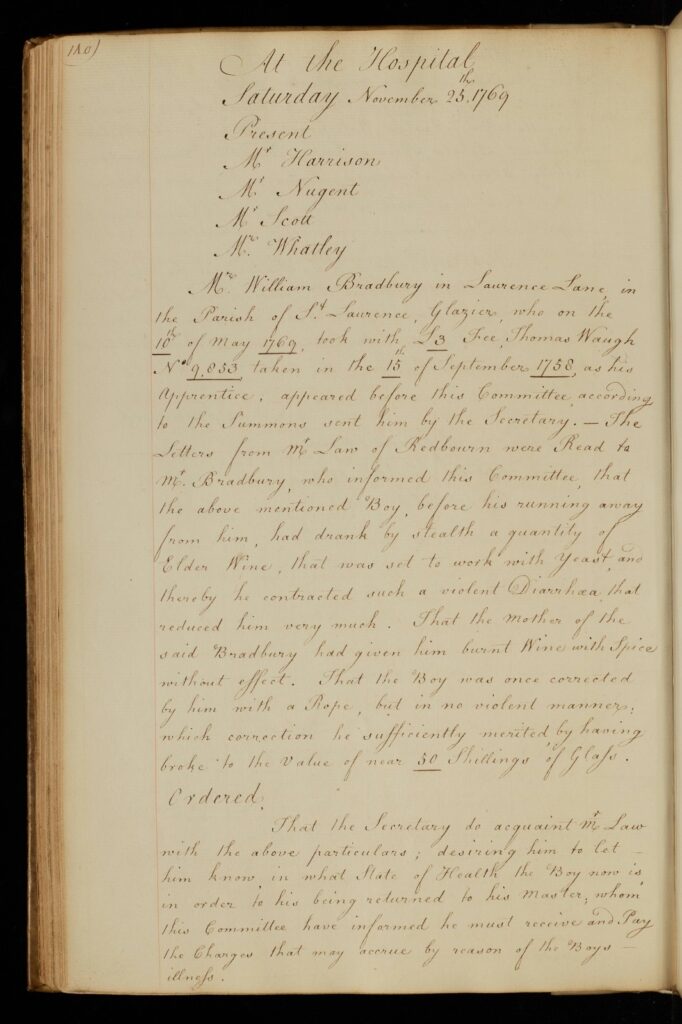

Four months later, Thomas’s story takes an interesting turn. On 25 November 1769, his master appeared before the Governors. Thomas had run away in September, after stealing and drinking a large quantity of Bradbury’s fermented elder wine, and contracting ‘violent diarrhoea’. Leaving an apprenticeship without permission was known as ‘elopement’ and viewed as a misdemeanour (Bright, 2017).

Sub-committee minutes: A/FH/A/03/005/008/170

Thomas had travelled to Redbourn, Hertfordshire, and was being looked after by Joseph Law, the Country Inspector who oversaw the Foundlings nursed by Elizabeth Taylor. The Sub-committee minutes from 6 January 1770 reveal that Law brought Thomas back to the Hospital, who returned him to Bradbury. A later entry from 3 March 1770 indicates that Thomas had run away twice more since then. This time, he had returned to Elizabeth Taylor.

The Governors criticised Taylor for ‘harbouring’ Thomas, and demanded that he was returned to his master:

“In the meantime…Mr Law do let the said Taylor know that neither this corporation or his said Master will pay anything towards his maintenance, and…[she] certainly is liable to an caution for retaining him.” (Sub-committee minutes A/FH/A/03/005/008/224)

Physical abuse

The Governors often cited reasons for a Foundling’s elopement: their age, their temperamental nature, or their desire to find a different job.

However, they also acknowledged physical abuse. The Governors state that Thomas was ‘ill-treated’: Bradbury had ‘corrected’ Thomas with a rope after he had broken 50 shillings’ worth of glass. Corporal punishment was routine in workplaces and institutions during the 18th century, which highlights the absence of workers’ rights in this period (Berry, 2019).

Nonetheless, Thomas was expected to return to his master. The Governors viewed his physical abuse as ‘sufficiently merited’. In other cases, Foundlings received further physical retribution from the Foundling Hospital (Bright, 2017), or faced local Magistrates who could force their return (Berry, 2019).

A rising trend

Thomas was one of many Foundlings who went back to the women who nursed them.

Elopement became such an issue that on Saturday 9 March 1771, the Foundling Hospital sent out 250 letters to their Country Inspectors, to encourage the return of children who have ‘run away to the places where they had been Nursed’. The subsequent correspondence between Inspectors and Governors highlights the breadth of this issue and the efforts of the Foundling Hospital to send apprentices back to their masters. Historian Helen Berry attributes these measures to the Hospital’s desire to ‘preserve their own authority and credibility with employers, and to maintain good social order’ (Berry, 2019, p.115).

There is no surviving evidence for the relationship between Thomas Waugh and Elizabeth Taylor. However, it is notable that he lived with her twice, and only left her care four months before he was apprenticed. A consequence of the General Reception was that children spent longer with their nurses, as the Foundling Hospital did not have the resources to house them. Foundlings were also apprenticed at a younger age in the mid-18th century (Bright, 2017). These conditions facilitated profound relationships that continued into adolescence. Letters in the Foundling Hospital Archive demonstrate that it was not just the Foundlings who developed strong emotional bonds – nurses would often ask to adopt the children they cared for, or visit them in the Hospital (Phillips, 2019).

A familiar tale

A comparable and contemporary example is John Coldfield, who was admitted on 27 December 1759 and assigned the number 14939. He was nursed by Martha Turner in High Ongar, Essex.

Much like Thomas, John lived with his nurse until he was ten years old, and was quickly apprenticed. Just two days after his return to the Foundling Hospital, he was indentured to John Bracher, a candle maker on Rose Lane, London.

By 23 June 1770, John had already returned to Martha Turner ‘several times’. He was brought before the Governors, ‘admonished’, and returned to Bracher. However, the Governors heard on 10 November 1770 that John had eloped again – reportedly to avoid being sent to sea.

John was physically abused by his apprentice master. His Country Inspector, William Brecknock, noted that John appeared ‘in a starving condition’ – and had ‘holes in his legs so that he could not walk’. Despite this, the Foundling Hospital blamed both John and Martha Turner:

“The sufferings he endured come from his own incorrigibility. And the tenderness of his nurse is very wrong placed and had she acted otherwise, the Boy hardly would have so often eloped from his master who only has lawful dominion over him.” (Sub-committee minutes A/FH/A/03/005/009/096)

John also faced physical punishment from the Foundling Hospital, who intended to whip him for his repeated elopement. This was later rescinded, as the Governors were satisfied with his apology.

The Governors eventually contacted a local magistrate to get an order for John to return to his apprenticeship. Instead, the magistrate took responsibility for finding him a different master. As a result, John was reassigned on 22 May 1771 to Francis Pimnor, in the trade of husbandry. He is not mentioned in the Sub-committee minutes again, perhaps indicating he was happier in this apprenticeship.

Some final thoughts

Unlike John Coldfield’s story, Thomas Waugh’s story does not have a clear resolution. It also raises several questions.

How did Thomas trek from London to Hertfordshire? Did he walk, or hitch-hike? He would have returned to the Foundling Hospital by vehicle, as his Country Inspector was financially compensated for the travel.

Why wasn’t Thomas reassigned? Evidently, the Governors were not interested in how Foundlings felt about their apprenticeships. It is also possible that they did not have the resources to transfer Thomas to a new master. The General Reception meant that a greater number of children required an apprenticeship in the late 1760s – potentially reducing the Hospital’s capability to reassign Foundlings. In general, apprentices changed trades if their master died, they were abandoned, or an external figure was willing to hire or reallocate them (Bright, 2017). The indenture fee also had to be paid back to the Foundling Hospital – either by the original master, or a magistrate (Berry, 2019).

What happened to Thomas? He is not mentioned again in the Sub-committee minutes, and his apprenticeship record does not include a second trade. If nobody was willing to hire Thomas, or pay his indenture fee, then he would have been returned to Bradbury.

Bibliography

Founding Hospital Archive

Apprenticeship Registers:

A/FH/A/12/003/001/243

A/FH/A/12/003/001/250

Billet Book: A/FH/A/09//001/111/111

General Registers:

A/FH/A/09/002/003/083

A/FH/A/09/002/004/223

Nursery Books:

A/FH/A/10/003/006/036

A/FH/A/10/003/007/047

Sub-committee Minutes:

A/FH/A/03/005/008/170

A/FH/A/03/005/008/197

A/FH/A/03/005/008/223

A/FH/A/03/005/008/224

A/FH/A/03/005/009/039

A/FH/A/03/005/009/050

A/FH/A/03/005/009/078

A/FH/A/03/005/009/083

A/FH/A/03/005/009/096

A/FH/A/03/005/009/099

A/FH/A/03/005/009/115

A/FH/A/03/005/009/134

A/FH/A/03/005/009/149

A/FH/A/03/005/009/163

A/FH/A/03/005/009/171

A/FH/A/03/005/009/168

A/FH/A/03/005/009/184

Secondary Literature

Berry, Helen (2019) Orphans of Empire: The Fate of London’s Foundlings. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bright, Janette (2017) ‘Fashioning the Foundlings – Education, Instruction, and Apprentices at the London Foundling Hospital c.1741-1800’, Master’s Thesis, University of London: https://sas-space.sas.ac.uk/6639/ (accessed 19/09/23)

Philips, Claire (2019) ‘Child Abandonment in England, 1741–1834: The Case of the London Foundling Hospital’, Genealogy, vol. 3, no. 3, https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3030035 (accessed 19/09/23)

Copyright © Coram. Coram licenses the text of this article under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 (CC BY-NC).