Out of 27,000 Foundlings, only around 3% were successfully reclaimed. The lives of the parents who claimed them and how they managed to reshape their lives in what was often a short space of time are interesting to consider.

This is what drew me to researching Foundlings Sarah Eustace (Foundling number 17870) and Catherine Hawkins (Foundling number 17934). Both babies were brought to the Hospital by their unmarried mothers, only to be successfully reclaimed a few months later.

The Case of Jane Harrison

Sarah Eustace was admitted at six months old, on 6 September 1783. Just three months later, she was discharged and returned to her mother, Jane Harrison. Jane’s petition letter to the Foundling Hospital, dated 11 June 1783, shed light on her situation. Jane was ‘not able to support her child any longer, and the father of the child [had] gone away and not to be found’; little else is known about the father. This resulted in ‘the mother of the child being in great distress at the time’.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, women faced constrained agency within a patriarchal society, amplifying the stigma of unmarried motherhood. Limited financial means forced them into dependency, relying on men for support. Thus, father abandonment emerged as a prevalent issue, evident in the thousands of petition letters in Coram’s Foundling Hospital Archive.

While the term ‘patriarchy’ encapsulates a key aspect of this context, it is essential to delve deeper into the multifaceted challenges at play. Absence of welfare and social services deepened the plight, affecting not only women but also working-class men. In this era, religion wielded considerable influence too, casting a moral shadow on extramarital relations. Religious sentiments fostered a climate of condemnation for those deemed to have transgressed societal norms. Thus, intricate societal, economic, and religious dynamics shaped the narratives of Foundlings and their mothers.

The petitioners to the Hospital required a reference, for which Jane turned to Mrs Williams. Mrs Williams stated that ‘the petitioner has lodged with her [for] about 5 months and that she is in distress’. The petition letter, along with Mrs Williams’s reference, suggests that Jane began her stay with Mrs Williams around the time Sarah’s father left, leaving Jane alone with the baby. Single pregnant women of the time would often give birth in lodgings or parish workhouses – such could be the case for Jane as she resided with Mrs Williams at the time of Sarah’s birth. While it is uncertain how Jane was paying for her stay, it can be assumed that after five months, she started to struggle to look after Sarah without the financial means to pay for their accommodation and basic expenses.

Admitting and reclaiming her daughter

Jane was among the 25 women who appeared before the Foundling Hospital Committee on 6 September 1783, when only 14 babies were admitted. Her baby was baptised Sarah Eustace on the same day and then sent to a nurse, Sarah Martin, of Mereworth, Kent, two days later.

Jane wrote to the Hospital again on 26 November to reclaim Sarah. It is unclear how Jane managed to turn her life around in the space of three months, but Jane must have made a compelling case. She convinced the Foundling Hospital that she could take care of the child as she was able to successfully claim her by the start of December.

- Jane Harrison’s original petition letter A/FH/A/08/001/001/014/054/a1. Click to enlarge.

- Jane Harrison’s claim petition A/FH/A/11/002/017/003/a1. Click to enlarge.

The Case of Sarah Ball

Most Foundlings were reclaimed when very young, between the ages of two months and five years old, with their mothers submitting claim letters stating that they could now support their child. Similar to Jane Harrison and Sarah Eustace is the story of Catherine Hawkins, who was reclaimed by her mother, Sarah Ball.

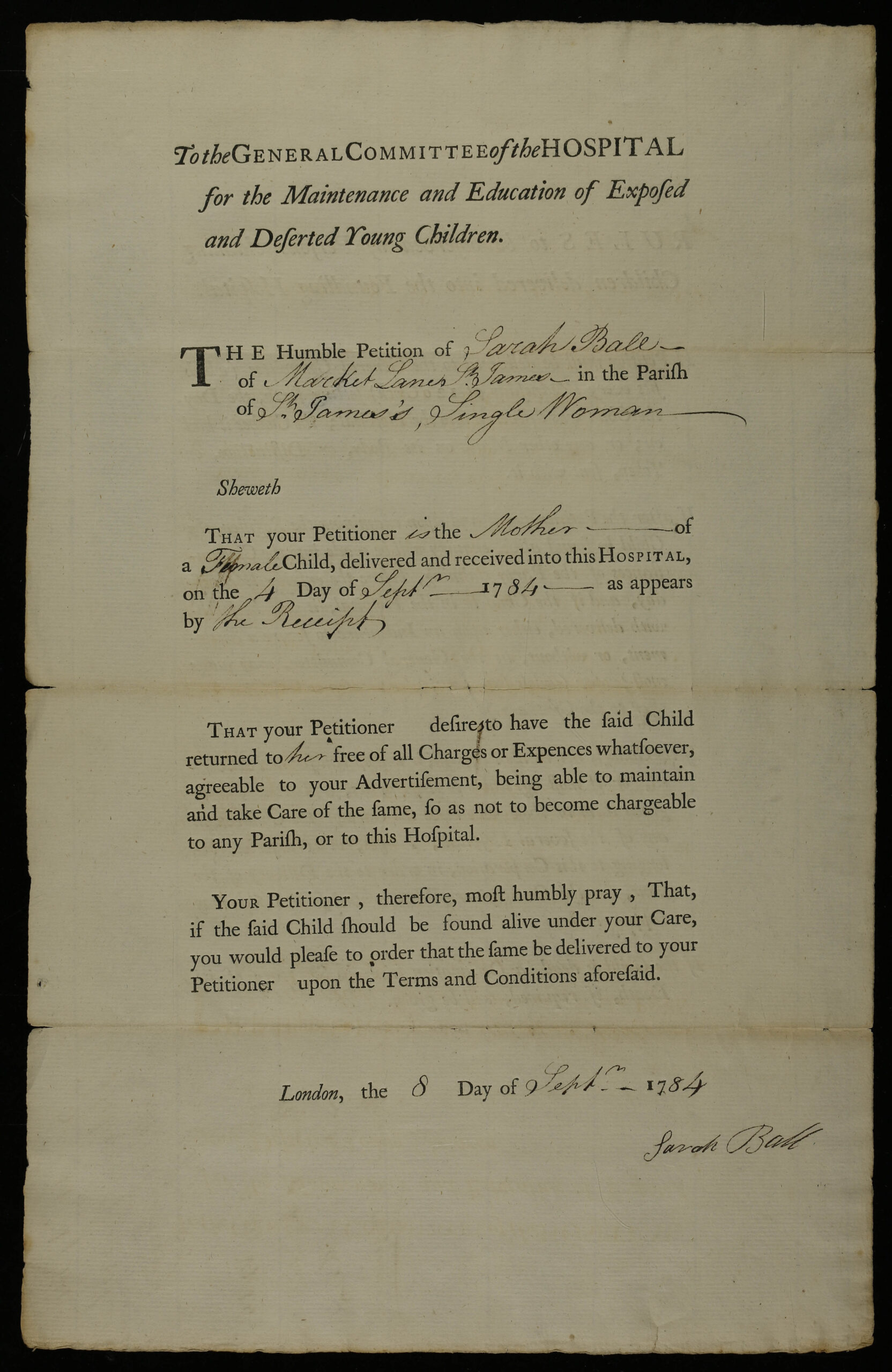

Sarah Ball had initially attempted to admit Catherine at 11 weeks old as she appears on the ballot sheet for 3 July 1784, but they were denied as Sarah drew a black ball. Her inability to take care of Catherine must have persisted as she reappears two months later and was successful: Catherine was admitted to the Foundling Hospital on 4 September 1784 at five months old. However, Sarah must have immediately regretted giving away her daughter as she came back only four days later, on 8 September, to ask for her daughter to be returned.

On this date, the Sub-committee minutes record an enquiry to Mrs Farmer about whether Sarah could now maintain and care for her child. The Farmers, who were known to have a good reputation in their neighbourhood, had previously provided Sarah’s reference when admitting Catherine. (Mr Farmer was a coachmaker in Haymarket, London.) They had known Sarah for ten years as she had been their servant on two occasions. They were clearly fond of Sarah as they further stated that ‘if they were not already provided with a servant, [they] would take her again’. The implication here may be that she was currently unemployed.

Their original reference also sheds light to Sarah’s situation, which led her to admitting Catherine. They had heard that Catherine’s father – a gardener’s head servant in Fulham, who they referred to as Sarah’s ‘seducer’ – had ‘absconded’ and left Sarah with a ‘helpless infant’ that Sarah was unable to provide for. One can deduce that this refers to Sarah’s financial ability to care for her child after Catherine’s father left. This resembles the circumstances of Jane Harrison.

It is not known how the Farmers responded to the Sub-committee’s enquiry, after Sarah’s application to claim her child, but something caused a delay. Catherine, who had been sent to a nurse in the countryside on 4 September, was returned to her mother on 8 June 1785.

It is worth noting that both Jane Harrison and Sarah Ball reclaimed their daughters by themselves – there was no mention of a husband. Instead, they sought out other ways, such as through employment. For instance, the claim register noted that in June 1785 Sarah Ball was a servant to Abraham Buzaglo – the ‘warming machine’ maker on the Strand, London. The new-found financial security through her employment explains how Sarah was able to reclaim her child alone.

- Sarah Ball’s original petition letter A/FH/A/08/001/001/015/050/a1. Click to enlarge.

- Sarah Ball’s claim petition A/FH/A/11/002/018/001/a1. Click to enlarge.

Conclusion

These cases highlight the disproportionate challenges and uneven responsibilities that fell on women. They faced stigma for being unmarried while pregnant and the hardships of supporting themselves and the child in a patriarchal society. These stories also show the strong emotional ties that caused them to return and reclaim their child.

Yet, despite the challenges and stigma single mothers faced at the time due to gender discrimination, they were not helpless. They were resourceful – as proven by Jane Harrison and Sarah Ball, who both managed to successfully reclaim their child by changing their life circumstances without a husband. It is a mother’s love for her child that drove them to reshape and change their life, allowing the Foundling Hospital to deliver Sarah Eustace and Catherine Hawkins back to their mothers within a short period.

Bibliography

Foundling Hospital Archive:

Sarah Eustace

Petitions Admitted to Ballot: A/FH/A/08/001/001/014/054/a1-a2

Sub-committee Minutes: A/F/A/03/005/017/096

General Register: A/FH/A/09/002/005/078

Baptism Register: A/FH/A/14/004/001/412

Claim Petition: A/FH/A/11/002/017/003/a1-b

Apprenticeship/Claim Register: A/FH/A/12/003/001/363

Catherine Hawkins

Petitions Admitted to Ballot: A/FH/A/08/001/001/015/050/a1-a2

General Register: A/FH/A/09/002/005/084

Baptism Register: A/FH/A/14/004/001/418

Claim Petition: A/FH/A/11/002/018/001/a1-a2

Sub-committee Minutes: A/FH/A/03/005/017/274

Apprenticeship/Claim Register: A/FH/A/12/003/001/363

Secondary sources:

“Access to History: Britain 1783-1885.” Hodder Education.

Brownlow, Emma. “The Foundling Restored to its Mother.” Foundling Museum.

Callahan, Kathy. “Women, Crime, and Work: The Case of London 1783-1815.” Marquette University, 2005. https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/400/

Pugh, Gillian. London’s Forgotten Children: Thomas Coram and the Foundling Hospital. Hardcover. 1 Mar. 2007.

Sheetz-Nguyen, Jessica. Victorian Women, Unwed Mothers and the London Foundling Hospital. London, 2012, pp. 2-5.

Williams, Samantha. Unmarried Motherhood in the Metropolis, 1700-1850: Pregnancy, the Poor Law, and Provision. Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Copyright © Coram. Coram licenses the text of this article under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 (CC BY-NC).