Warning: Some of the historical language used in this article may be seen as offensive. Find out more about the historical language in our archive.

On 18 March 1794 a baby was admitted to the Foundling Hospital. He was given the name John Hunt. Little is known about many of the women who gave their children to the hospital, but this is not the case for John’s mother. Thirty-six years earlier, in 1758, she herself had been admitted to the Hospital. She was given the name Rose Otway.

Rose’s admission

Rose was admitted to the Hospital, and given the number 8048, on 10 April 1758 during a period that was known as the General Reception. In 1756 Parliament had voted that all babies who were brought to the Foundling Hospital must be admitted. Parliament provided the Hospital with the financial support they thought would be necessary for this endeavour. General Reception came to end in 1760, however. It had cost Parliament more than £500,000, a level of funding they were no longer willing to provide. Over the four years that the General Reception lasted, the Foundling Hospital took in 6,293 ‘Parliamentary Children’, one of whom was Rose. As was the case for many of those 6,293 babies, nothing is known of Rose’s mother and father, or of her life before 10 April.

A week after she was admitted, Rose was sent to be wet-nursed by Sarah Lipscomb of Worplesdon, Surrey. All babies the Hospital received went to live with nurses in the countryside for the first few years of their lives. Rose returned to the Hospital five years later in September 1763. Whilst Rose’s early life was typical, as she grew older, her experience began to differ from that of an average Foundling. This was due to her physical health.

Rose’s disability

Rose appears in multiple lists of children with disabilities within the Infirmary Records. The Infirmary Records – which describe some children as ‘Deformed’ and as ‘Idiots’ – illustrate an archaic attitude towards physical and mental disabilities typical of the time. Rose is included within the category of ‘Lame’. The word ‘Lame’, in this context, was an ‘Early English term meaning restricted use of one or more limbs’ (Historic England). Rose is described as having a ‘stiff joint’. Elsewhere in the Hospital’s records, she is described as being ‘lame of the ancle’ and ‘having a stiff ancle’.

Despite the use of derogatory language, the 18th Century did see the beginning of a change in attitudes towards people with disabilities. Educators like Thomas Braidwood (1715-1806) and Edward Rushton (1756-1814) advocated for the education of children with disabilities. The Foundling Hospital similarly provided these children with opportunities they may not have been afforded had they lived at home. For example, blind children were taught to sing and play musical instruments. Physically disabled children like Rose often worked as servants and seamstresses at the Hospital when they reached the age at which Foundlings were usually apprenticed and left the care of the Hospital to live with their new master or mistress.

Working at the Hospital

Rose worked at the Founding Hospital with the coat makers. In the Sub-Committee minutes of 18 March 1769, when she was nearly 11 years old, she is listed as one of the girls who were ‘presented to [the] committee with coats of their own making’. All of the girls were given thimbles, and one girl, Mary Turner, was rewarded with a housewife – a type of small sewing kit – for being ‘particularly expert in coat making’. The Daily Committee minutes from 2 February 1771 reveal that Rose was made the assistant of Esther Yargrove, another Foundling who made and mended uniforms at the Hospital. As an older ‘servant’ girl, Rose would have been dressed in a green gown of calamanco (an inexpensive woollen material). This distinguished her from the younger Foundlings, whose uniforms were brown.

Rose worked at the Hospital until January 1775 when she was apprenticed to a ‘spinster’ called Jane Kerr in Hanover Square, London. Like many of the Foundling girls, Rose was employed in ‘household business’ (domestic service). However, Rose’s physical disability meant that she was returned to the Hospital in March after her mistress complained about her ‘bad legg’ (sic). She was re-apprenticed to the same woman in September 1776 after her return was requested. This is the last reference to Rose in the Hospital’s records until 1794, when she reappears in tragic circumstances.

Rose’s petition

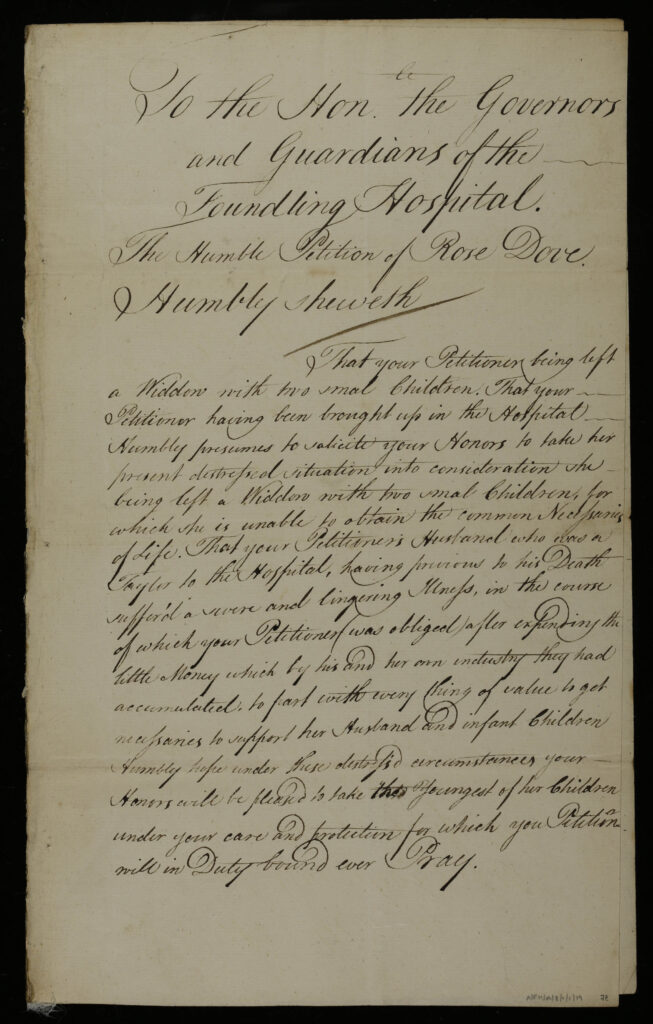

In 1794, Rose petitioned the Foundling Hospital to admit the youngest of her two children. Rose had married John Dove at St Bride’s Church, Fleet Street, London in July 1782. John was a tailor, who is mentioned many times in the Sub-Committee minutes in reference to his work for the Hospital. For example, he is referenced in December 1787 in a tradesman’s bill for ‘60 Boy’s [sic] waistcoats’. Rose’s petition letter revealed that John had died after a ‘severe lingering illness’ and left her a widow with two children. Destitute, she was unable to provide her children with the ‘common necessities’ of life. She was in a ‘distressed situation’ and needed the Hospital’s help. This is her petition letter:

Petition admitted to ballot: A/FH/A/08/001/001/019/078/a1

John’s admission

The Foundling Hospital accepted Rose’s petition and John Dove was admitted on 18 March 1794. He was nine months old and given the surname ‘Hunt’, and the number 18180. John remained under the Hospital’s care until he was apprenticed in September 1804.

He was first apprenticed to George Cartwright, a shoemaker in Notting Hill, London. However, four years later, John was accused of theft. At a Sub-Committee meeting in January 1808, attended by Cartwright, John ‘was on his expressing much contrition severely reprimanded’ and sent back to his apprenticeship to complete a trial month. At the Sub-Committee meeting held a month later, John’s employer repeated his complaints and John was ‘sent to sea’ as punishment.

It is unclear what this meant for John. Boys at the Foundling Hospital were sometimes sent to work in the sea-service and maritime industries for their apprenticeships, but over time it became more likely for Foundlings to be sent to work at sea as punishment (Berry, 2023). John could have been apprenticed by a mariner within the merchant navy, or he could have been recruited to the Royal Navy to fight in the Napoleonic Wars.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Foundling Hospital Archive

General Registers:

A/FH/A/09/002/002/454 Rose

A/FH/A/09/002/005/109 John

Billet Books:

A/FH/A/09/001/092/101 Rose

A/FH/A/09/001/194/053 John

Nursery Book: A/FH/A/10/003/005/204 Rose

Infirmary Book: A/FH/A/18/005/003 Rose

Apprenticeship Register:

A/FH/A/12/003/002/170 Rose

A/FH/A/12/003/002/244 John

Petition Admitted to Ballot: A/FH/A/08/001/001/019/078/a1-a2 (Rose’s petition letter about her son)

Sub-committee minutes:

A/FH/A/03/005/008/040 Rose

A/FH/A/03/005/009/139 Rose

A/FH/A/03/005/012/018 Rose

A/FH/A/03/005/012/247 Rose

A/FH/A/03/005/019/275 John Dove (father)

A/FH/A/03/005/027/300 John

A/FH/A/03/005/027/304 John

Secondary Research:

Berry, Helen. The Occupational Distribution of Foundling Apprentices during the English Industrial Revolution. Social History, vol. 48, no. 2, 2023, pp. 259–283, doi:10.1080/03071022.2023.2179747.

Cunnington, Phillis, and Catherine Lucas. Charity Costumes: Of Children, Scholars, Almsfolks, Pensioners. Adam & C. Black, 1978.

Historic England. Disability History Glossary historicengland.org.uk/research/inclusive-heritage/disability-history/about-the-project/glossary/

Mathisen, Ashley. ‘So that they may be usefull to themselves and the community’: Charting Childhood Disability in an Eighteenth-Century Institution. The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth, vol. 8 no. 2, 2015, p. 191-210. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/hcy.2015.0031.

Copyright © Coram. Coram licenses the text of this article under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 (CC BY-NC).