For many of the mothers who admitted their children to the Foundling Hospital, their paths would not cross again with their child. But in some rare cases, with a change to the mothers’ lives came the desire to be reunited. This was the case for the mothers of Foundlings Mary Meadmore and Catherine Dunk.

The case of Mary Meadmore

In 1826, the Foundling Hospital received a series of letters from Elizabeth Steele and her husband, William Cameron, requesting to be reunited with Elizabeth’s daughter. Eleven years before, in September 1815, Elizabeth had given the two-month-old baby girl to the Foundling Hospital, where she was named Mary Meadmore and assigned the number 19121. As stated in her petition letter then, Elizabeth did not know where the father of the child – William Davage – was. She believed that she could not care for her child alone – as was the story for many mothers who were similarly helped by the Foundling Hospital.

In 1826, Elizabeth and her husband wrote several letters in a desperate attempt to be reunited with Mary. In her claim letters Elizabeth never refers to her daughter by name, only as ‘my child’, because Mary’s new name was unknown to her. Elizabeth believed that she was finally in the position to care for her, as she was supported fully by her husband: ‘He told me I should be welcome to claim her when-ever I thought proper and that he would adopt her as his own’.

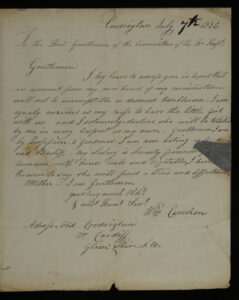

William was a gardener for the Traherne family, working on their estate in Coedriglan, near Cardiff. He wrote his own letter to the Foundling Hospital, stating that Mary would ‘be treated by me in every respect as my own’.

- A/FH/A/08/001/002/024/060/b: Letter from Elizabeth Cameron (1826). Click to enlarge.

- A/FH/A/08/001/002/024/060/a3: Letter from William Cameron (1826). Click to enlarge.

Elizabeth’s strength, along with her trust in her husband, is clear through their appeal. Most mothers of illegitimate children would struggle to tell anyone as it was considered to be a sin to have a child outside of marriage, much less to reveal this to their new husband. However, in the case of Elizabeth, who had William’s support to the extent that he was willing to adopt another man’s child, it can be assumed that their relationship was strong. To reclaim a child as old as 11 could open up social judgement because the illegitimacy of the child would be clear. In spite of this, Elizabeth was desperate to be reunited with her daughter. In her letters, Elizabeth also explains her new financial situation. With the death of her father, she came into money and planned to use this to justify the validity of her claim. Finances were taken into consideration when assessing parents’ ability to claim a child.

The claiming process

Claiming a child back from the Hospital was rare: of the approximately 27,000 children admitted, only around 3% were claimed by their birth parents. The process had strict rules, which were outlined in a single document. First, a petition must be made to the Hospital within which the parents must describe the child on the day of their admission. They had to be detailed: the date the child was admitted, the clothes they were wearing along with any tokens that were left with the baby, and any marks on their body. This was compared to the original billet sheet. This was important because upon admission children were baptised with new names and changed into new clothes; so, identifying the child could become hard, as the birth mother would not be aware of the child’s new name.

These claim petitions would include information on the mothers and why they believed that they could now care for the child. Although after 1764 it was no longer required that the parents had to pay a fee to the Foundling Hospital, it was often the case that the parents’ financial situation was outlined as a justification for their claim petitions. They had to prove that they could support a child. This was often an obstacle. Elizabeth Steele only attempted to claim Mary after she came into a large sum of money from her father’s passing.

Two names had to be given for security, before their ‘character and circumstances’ were assessed. If the parents managed to complete all the requirements, their child would be given back to them. Many parents, such as Elizabeth Steele and her husband, were successful; others received only a death certificate because the child had died in the interim; and some never completed the process – as was the case for Mary Brown.

The case of Catherine Dunk

On 25 February 1760, Mary Brown arrived at the Foundling Hospital with her three-month-old daughter. The child was admitted, baptised, and renamed Catherine Dunk (No. 15731). Four years later, as a widow, Mary contacted the Hospital hoping to reclaim her child. She followed all the required steps. She identified the child and paid the deposit, which was required at that time to reimburse the Hospital for the care of her daughter up until that point. However, she came to a problem. Mary failed the assessment of her ‘character and circumstances’.

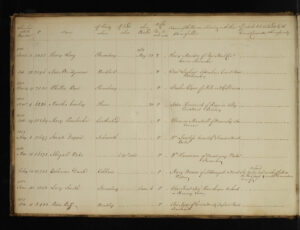

The claimed child register in the Coram’s Foundling Hospital Archive shows that her claim was refused, which was rare – this entry stands out among the many successful claims. At this time, Mary was working as a servant, but despite this, she was still deemed unsuitable by the Governors. This decision was made on the basis that Mary had another child she could not care for. According to the register: ‘Refused. The Mother having another Child in the Workhouse & unable to maintain herself’.

- Billet of Catherine Dunk: A/FH/A/09/001/172/067. Click to enlarge.

- Page from Claimed Child Register: A/FH/A/11/001/001/014. Click to enlarge.

As she never was reunited with her mother, Catherine lived out her youth within the care of the Foundling Hospital. At the age of 12, Catherine followed the path of many Foundling girls – becoming an apprentice in ‘household business’ until the age of 21. It was not unusual for girls in domestic service to find their apprenticeship difficult and be moved around. Catherine was apprenticed four times in London: to a cabinet maker, a widow, a letter carrier, and a milkman.

Bibliography

Foundling Hospital Archive

Mary Meadmore

Original petition letters (1815) and claim letters (1826): A/FH/A/08/001/002/024/060/a1-i3

General Register: A/FH/A/09/002/005/203

Baptism Register: A/FH/A/14/004/001/527

Catherine Dunk

Billet: A/FH/A/09/001/172/067

General Register: A/FH/A/09/002/004/302

Claim Petition: A/FH/A/11/002/005/008/a1-a2

Claimed Child Register: A/FH/A/11/001/001/014

Apprenticeship Register: A/FH/A/12/003/002/151

Copyright © Coram. Coram licenses the text of this article under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 (CC BY-NC).