A battalion captain, a shrewd petitioner, a pro-Scotland Hospital official, and a dependable tailor are the unlikely set of supporting characters in John Nelson’s story. His family history, the peculiar circumstances of his admission, and his two apprenticeships contribute to create a particularly rich portrait of the life and background of an early 19th-century Foundling.

The MacKinnons of Argyle, Nova Scotia

John Nelson’s mother was Elizabeth Letitia MacKinnon. Like many other women whose children were accepted at the Foundling Hospital, she had hers with a man she was not married to. He was called John Fountain and, in spite of Elizabeth’s pregnancy, he decided to leave the country. She was left with her needlework as her only source of income, the responsibility of a baby born out of wedlock – a damning condition for a woman at the time – and too much shame to ask for her family’s help. Some of her father’s friends assisted her with small donations until one of them, Alexander Thompson, decided to write to the Foundling Hospital on her behalf.

The letter petitioning for her child’s admission provides an unusual amount of detail on Elizabeth’s background. There, we learn that her father was Ranald MacKinnon (c.1737-1805), captain of the 2nd Battalion of the British army’s 84th Regiment, the Royal Highland Emigrants. From 1757, he fought in North America against the French and the Cherokees. During the American Revolution, he distinguished himself in leading a successful raid at Cape Sable Island, off the coast of Nova Scotia (now part of Canada).

Originally from the island of Skye in Scotland, Captain MacKinnon ended up marrying Letitia Piggott and making his home in Nova Scotia. The British Government gave him extensive grants of land there as a reward for his service. Later, he became the magistrate for the Argyle district, which he named after the corresponding Argyll region in his motherland. Elizabeth, his eldest child, was born in Argyle in 1767.

It is not clear when or why she moved to London. It is possible she did so with her first husband, Ebenezer Hobbs, who soon left her a widow. It is equally uncertain whether she ever travelled back to Nova Scotia. Her conspicuous absence from her father’s will, written in 1801 and executed in 1810 by her mother, suggests that she did not. It is impossible to know whether her family thought her lost or dead, or whether they knew of her circumstances and had decided to cut her off completely. We can hope it was the former. According to Mr Thompson’s letter, Elizabeth had changed her name to Mrs Brooks once in London to conceal her origins. This would have certainly made keeping track of her more difficult for the MacKinnons.

The art of effective petitioning

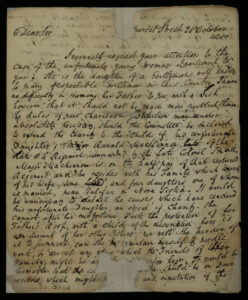

As a norm, petitions were addressed in general terms to the Foundling Hospital’s Governors. Alexander Thompson, however, did the exact opposite: his letter on behalf of Elizabeth MacKinnon was sent specifically to one Governor, George Glenny, Esq. Due to a lack of information on Mr Thompson, it is difficult to gauge how or how well sender and recipient knew each other. Nevertheless, the petition reveals that the two had spoken before and that Glenny would be in charge of presenting Elizabeth’s case.

Glenny was a member of the General Committee, a small elected body tasked to manage the Hospital’s affairs, including reviewing petitions. There is reason to believe that Glenny was not simply petitioned as a member of the Hospital, but that he was quite carefully targeted as someone who Thompson knew would have particular sympathy for Elizabeth’s case.

In fact, George Glenny was a governor for life – and a vice-president – of the Scottish Hospital of the Foundation of King Charles II, an organisation assisting poor Scotsmen in London. Moreover, in 1798 he had made a donation to assist the widows and children of English soldiers who fought in Ireland. Two years later, he joined a subscription scheme for a monument to the Royal Navy in Greenwich. As a woman of Scottish descent whose father had had a military career of some distinction, Elizabeth MacKinnon did fit Glenny’s philanthropic interests remarkably well.

Thompson’s petitioning strategy evidently worked: Elizabeth’s seven-month-old son was admitted into the Foundling Hospital on 27 October 1800 as Foundling Number 18610, and renamed John Nelson.

- Petition Letter A/FH/A/08/001/002/009/001/a1

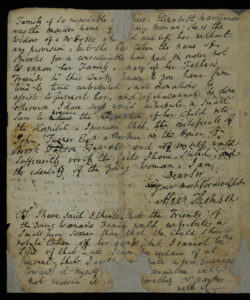

- Petition Letter A/FH/A/08/001/002/009/001/a2

On payment and admissions – a moral conflict

Besides Elizabeth’s background, Alexander Thompson used another argument to support her child’s admission to the Hospital: money. In his own words: ‘I would … [do]nate a few Guineas towards it [the admission] myself’. More funds, he suggested, would potentially come from the friends who had been helping Elizabeth up to that point.

While there was a preference for the admittance of babies under two months of age, donations of £100 did occasionally make their way to the Hospital to ensure that slightly older children were admitted. Four such cases were recorded in 1800 alone. The practice of paid admissions was increasingly criticised, however, because it forced the Hospital to accept those children, regardless of their parents’ circumstances.

While Thompson’s ‘few Guineas’ did not amount to £100, his offer did come at a critical point in the development of the Hospital’s admissions policy. Scarcely three months later, in January 1801, paid admissions were abolished altogether.

John Nelson, prospective calico printer

John’s early years at the Foundling Hospital were not very different from his peers’. He was baptised the day after admission and immediately sent to a nurse in Addlestone, Surrey. Silence about him in the Hospital’s records until 1813 – when he was confirmed – suggests a sufficiently well-behaved childhood.

In accordance with the Hospital’s policies, John was first apprenticed at age 14. Apprenticeships were a common way of teaching young people a profession, thus ensuring they would be able to provide for themselves in adulthood. Apprenticeships to a trade lasted seven years. Apprentices would spend this time living with and learning from their master, a professional in a particular trade, in exchange for their work.

The Foundling Hospital often placed boys in skilled trades. The proliferation of manufacturing workshops in northern England during the Industrial Revolution meant that a considerable proportion of the Hospital’s wards was sent there. This is what happened to John too: his first master was Thomas Andrew Jr, a calico printer of Harpurhey, near Manchester.

Calico was a fashionable textile in the period. It was imported from India and then dyed in the UK, where calico printing was a flourishing trade. In the 1760s, the Hospital had sent groups of girls to be apprenticed in this profession, with disastrous results: the apprentices were severely mistreated. The Foundling Hospital sought to avoid group apprenticeships thereafter. This is why it is so surprising to hear not only that John was apprenticed to a calico printer, but also that at least another eight Foundlings joined him under the same master in 1814-1816. It is possible that the Hospital thought being boys would be protection enough for them, or perhaps the Governors were confident about Mr Andrew’s good character.

John Nelson, apprentice tailor

John’s time with Mr Andrew abruptly came to an end in 1816. From March onward, we find John’s name in the daily lists of patients in the Foundling Hospital’s infirmary, accompanied by a diagnosis of ‘ulcer’d leg’.

By early 1817 John could walk, but he was ‘far from well’. Intense physical labour and exposure to excessive dampness were to be avoided for at least one more year. This was the medical opinion of Dr Henry Earle (1789-1838), then assistant surgeon at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London. The verdict of this respected professional – who was to become surgeon-extraordinary to Queen Victoria – meant that John did not return to the demanding, water-based operations of calico printing despite Mr Andrew’s ‘strong wish’ to have him back.

The same care displayed by the Hospital for John’s health was applied to finding him a new apprenticeship. At the Foundling Hospital, this was the Secretary’s responsibility. Assisted by the Steward, he would contact a network of inspectors and associates who would look for a suitable candidate among their contacts.

For John, this turned out to be William Balmer, a tailor living in Bethnal Green, London. In keeping with the Hospital’s preferences, Mr Balmer was ‘of the Protestant Religion, a Housekeeper and married’. Moreover, the reference provided by the Secretary’s contact, Edward Smith, draper of Houndsditch, described Balmer as ‘a good worker, who is steady and can be depended upon’. The apprenticeship was approved on 17 December 1817. After more than 19 months in the Hospital’s infirmary, this date marked John’s discharge.

It is interesting to notice that John’s long convalescence was not taken lightly by the Hospital or his new master. Indeed, the Secretary had endeavoured to place him in a trade which would help his physical recovery. Mr Balmer, on his part, insisted on a probation period of 10 days before the official start of John’s apprenticeship, and the payment of a £10 premium as insurance. Moreover, both parties agreed that, should John’s leg make him unable to work, the Committee would procure him an admission into St Bartholomew’s Hospital.

We can only imagine John’s fate after his apprenticeship. Although he would have been cared for if his health deteriorated again, it is nicer to picture him as the established, fully recovered tailor that the Hospital hoped he would become.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Foundling Hospital Archive:

Apprenticeship Register: A/FH/A/12/003/002/261

Baptism Register: A/FH/A/14/004/001/482

General Register: A/FH/A/09/002/005/152

Nursery Book: A/FH/A/10/003/007/250

Petitions Admitted: A/FH/A/08/001/002/009/001/a1-a5

Petitions for Apprentices: A/FH/A/12/01/063/1

Sub-committee Minutes: A/FH/A/03/005/030/103; A/FH/A/03/005/030/153-154; A/FH/A/03/005/030/251

Weekly Reports on the Sick in the Infirmary: A/FH/A/18/005/009

The National Archives:

PROB 11/1512/154

Primary sources:

An Account of the Institution, Progress, and Present State of the Scottish Corporation in London, of the Foundation of King Charles the Second Re-Incorporated Anno MDCCLXXV by His Present Majesty King George III and Established at the Hospital in Crane Court Fleet Street (London: Bunney, Thompson, & Co., 1797)

A List of Governors and Guardians of the Hospital for the Maintenance and Education of Exposed and Deserted Young Children (London, 1799)

Morning Post, 27 Nov 1802 at Gale Primary Sources, at https://www.gale.com/intl/primary-sources [accessed 03/06/2023]

Oracle, 17 Dec 1799 at Gale Primary Sources, at https://www.gale.com/intl/primary-sources [accessed 03/06/2023]

Oracle, 25 Jan 1800, at Gale Primary Sources, at https://www.gale.com/intl/primary-sources [accessed 03/06/2023]

True Briton, 4 July 1798 at Gale Primary Sources, at https://www.gale.com/intl/primary-sources [accessed 03/06/2022]

Secondary sources:

Berry, Helen, Orphans of Empire: The Fate of London’s Foundlings (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019)

Brown, George S., Yarmouth, Nova Scotia: A Sequel to Campbell’s History (London: Forgotten Books, 2013)

Moore, N. and J. Loudon, ‘Earle, Henry (1789–1838), surgeon’, in David Cannadine (ed.), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2022, first published 2004) at https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-8397 [accessed 08/08/2023]

‘Muster Books and Pay Lists: 84th (Royal Highland Emigrants) Regiment of Foot: 1778-1798’, The Loyalist Collection, University of New Brunswick, at https://loyalist.lib.unb.ca/node/4722 [last accessed 08/08/2023]

Nichols, R. H. and F. A. Wray, The History of the Foundling Hospital (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1935)

Pugh, Gillian, London’s Forgotten Children: Thomas Coram and the Foundling Hospital (Cheltenham: The History Press, 2022)

Copyright © Coram. Coram licenses the text of this article under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 (CC BY-NC).