In 1849, the Foundling Hospital asked Catherine Dickens, wife of Charles Dickens, to provide a character reference for an unmarried woman unable to support her child. Twenty years later, another literary figure would come to feature in the child’s life.

In January 1849, a month after giving birth to her baby daughter, Mary Cheeseman took up a position at No. 1 Devonshire Terrace, London, the home of author Charles Dickens. She was employed as a wet nurse to his eighth child, Henry Fielding Dickens, who had been born on 16 January. It was common practice for wealthier families to employ a nurse to breastfeed babies in place of their mothers. Women who had recently given birth were hired while they were still able to breastfeed. For an unmarried, unemployed woman like Mary, this was a vital opportunity to earn a living and support her baby.

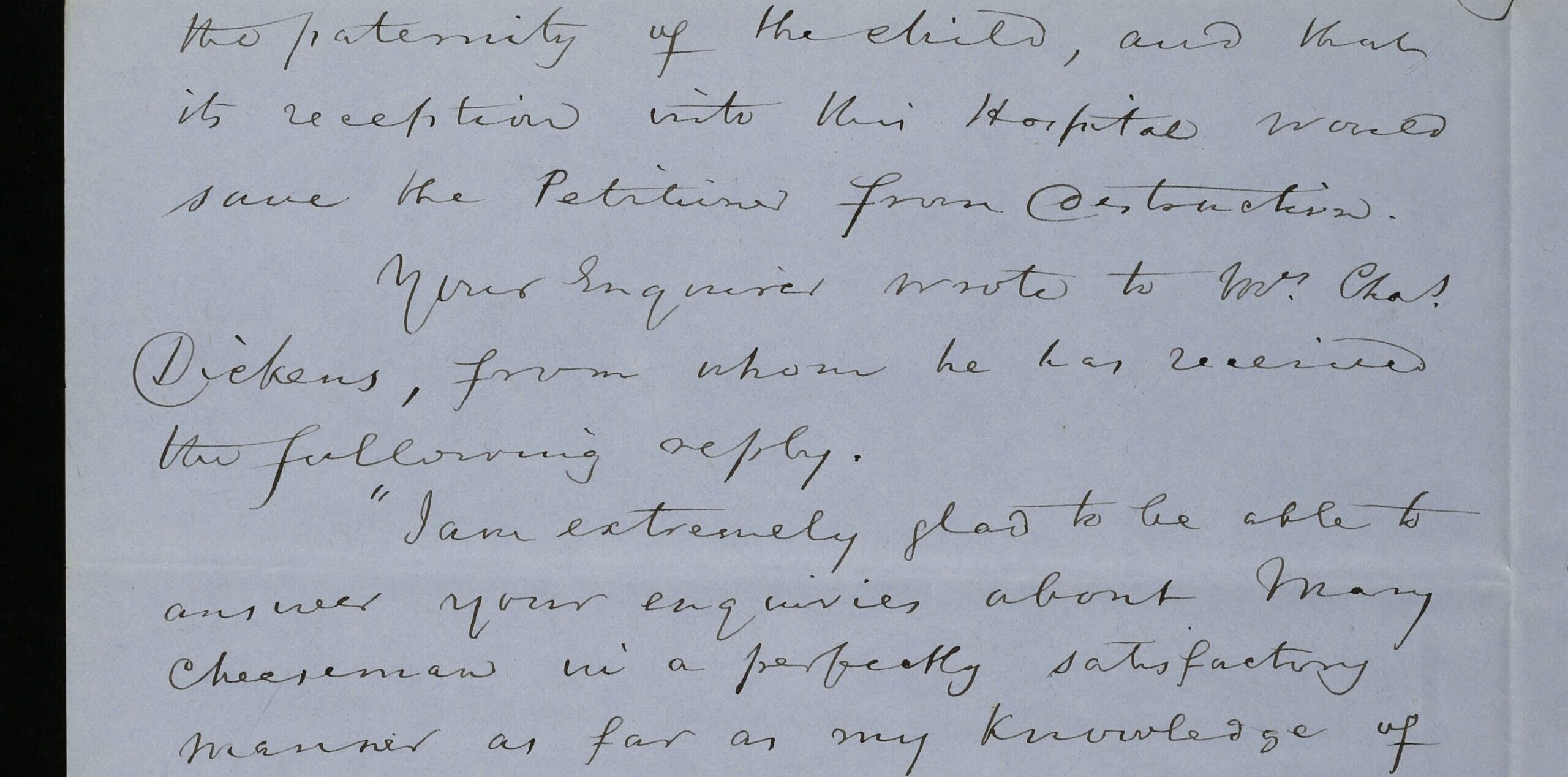

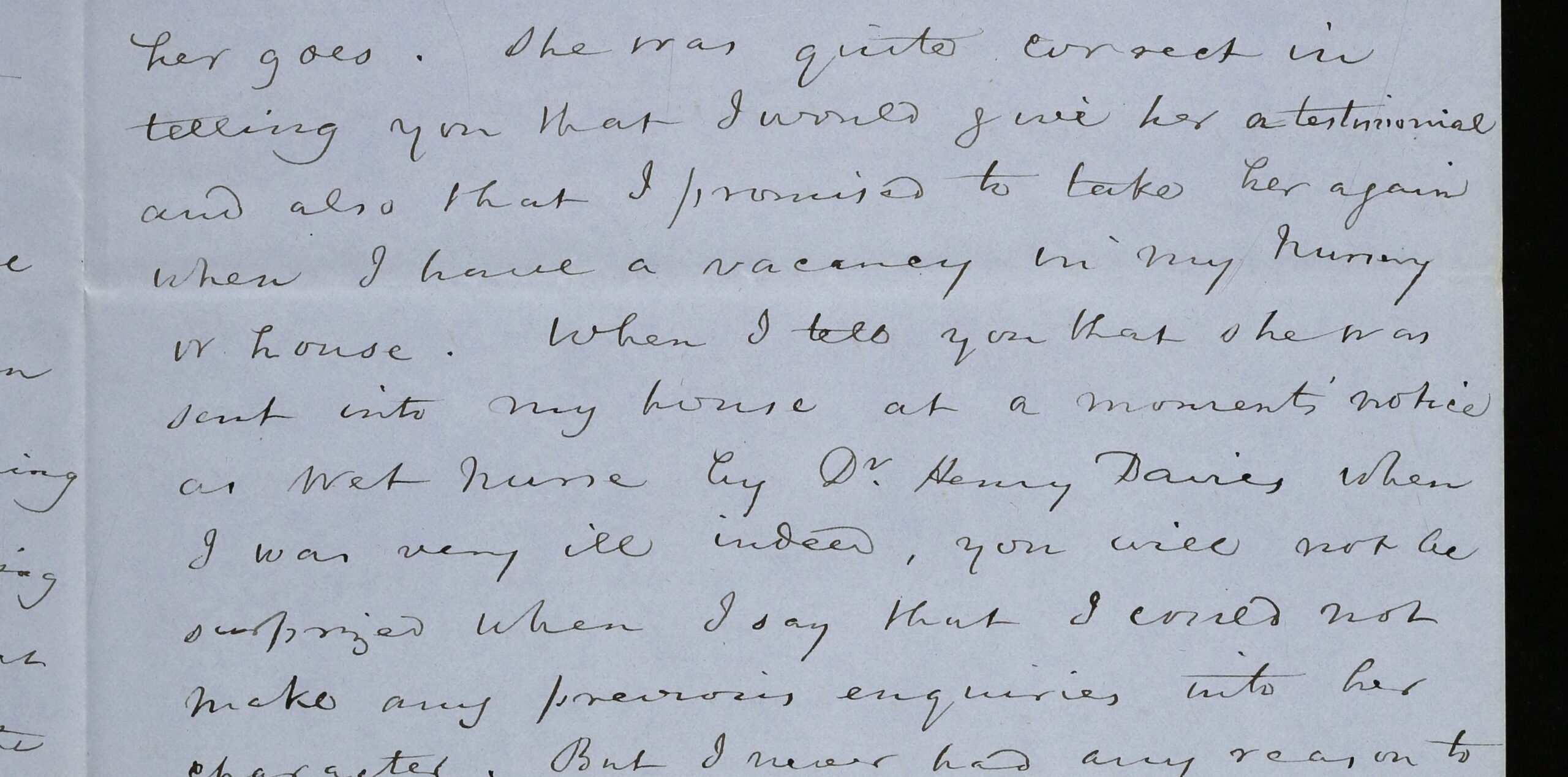

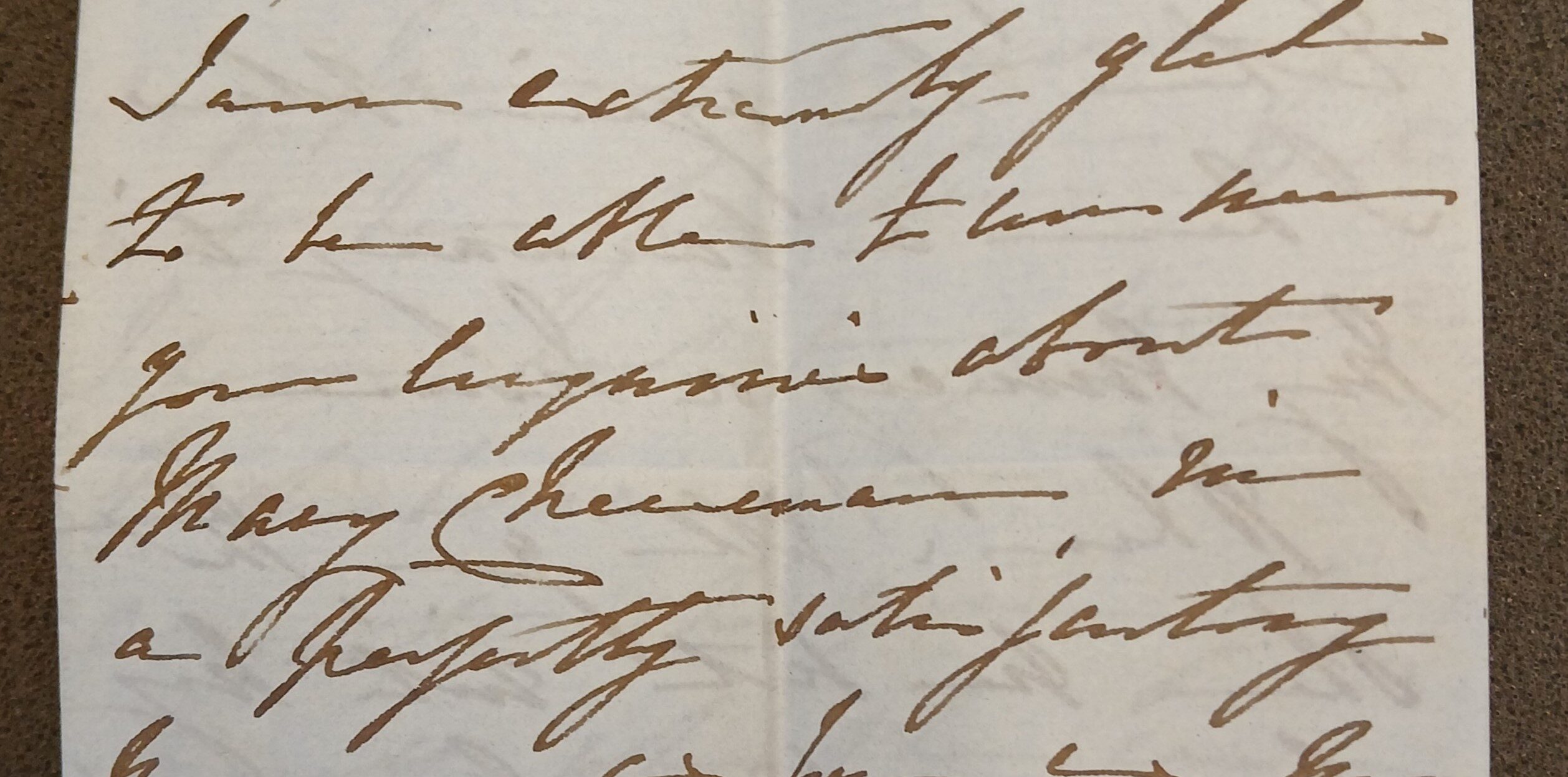

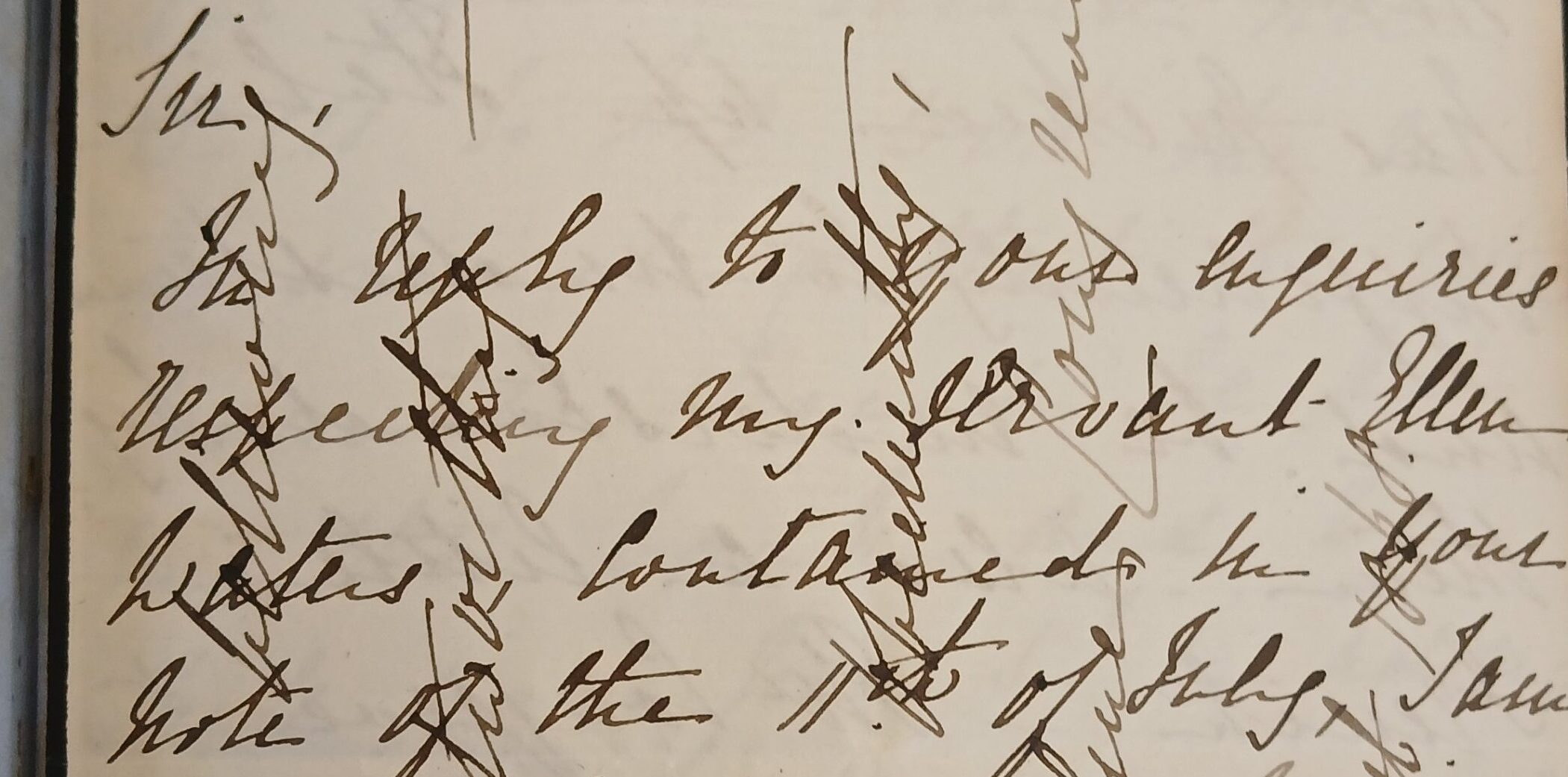

Mary lived with the family for seven weeks in the house where many of Charles Dickens’s famous works were completed, including David Copperfield and A Christmas Carol. Sadly, her employment was cut short when she stopped producing enough milk to feed the baby. When the Foundling Hospital contacted Catherine Dickens to request a character reference a few months later, her response was complimentary:

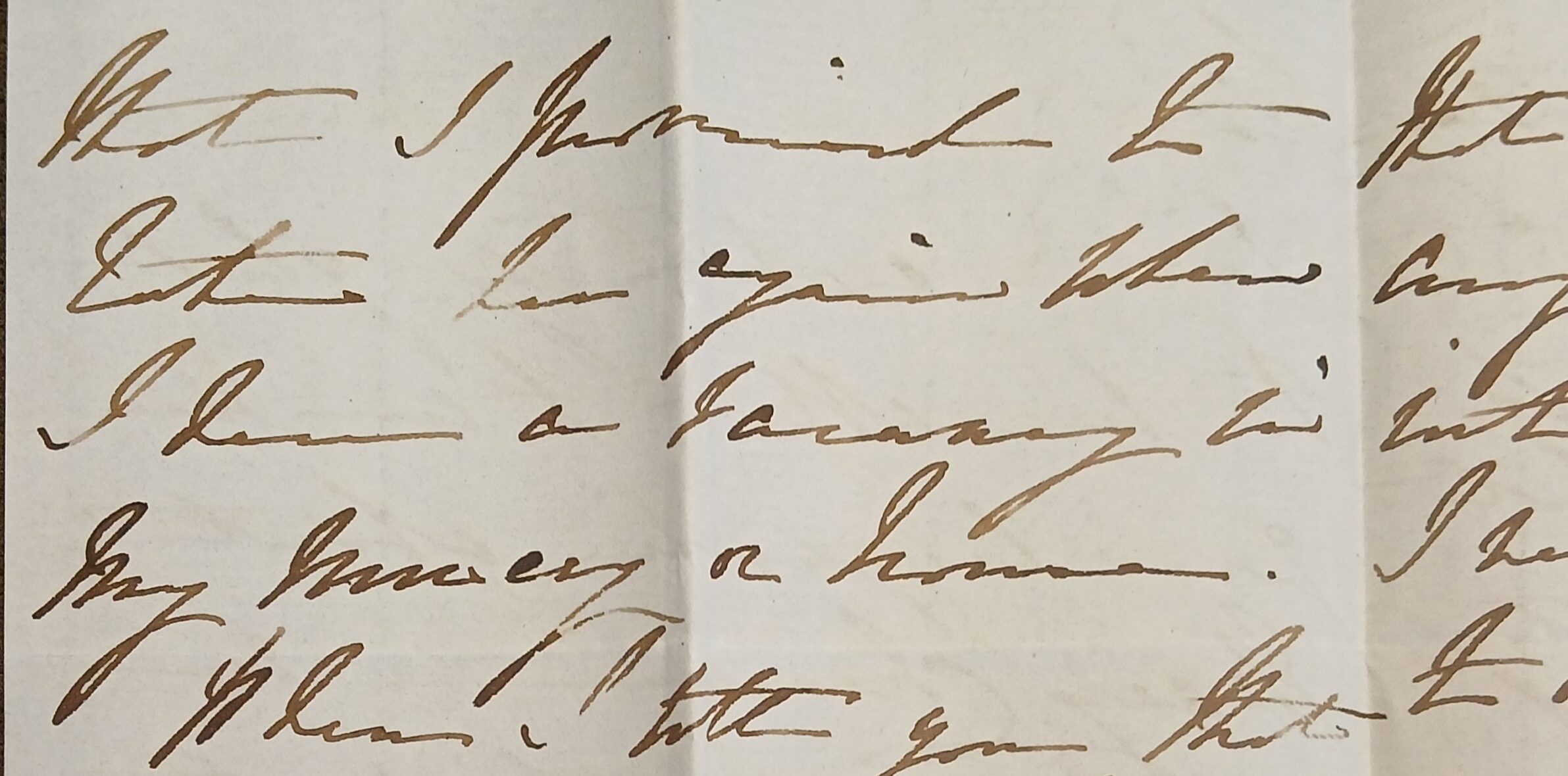

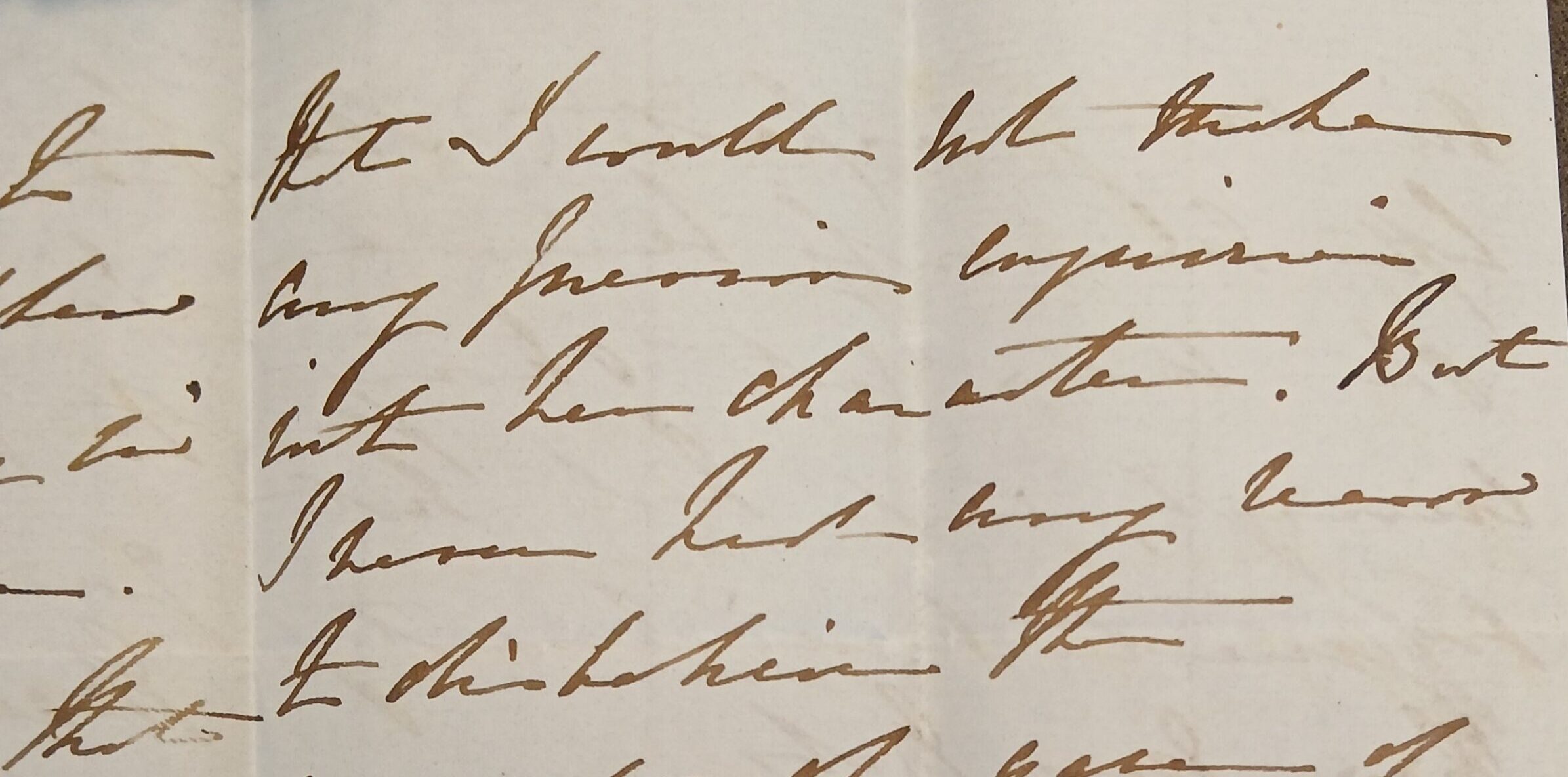

“I promised to take her again when I have a vacancy in my Nursery or house… Her conduct during the short time she remained in my establishment was perfectly unexceptionable in every respect. She left me only because she was not strong enough and had not sufficient nourishment for my Baby. I shall be very glad if this Letter has any influence in assisting her in getting her child into the Foundling Hospital.”

Mary’s story

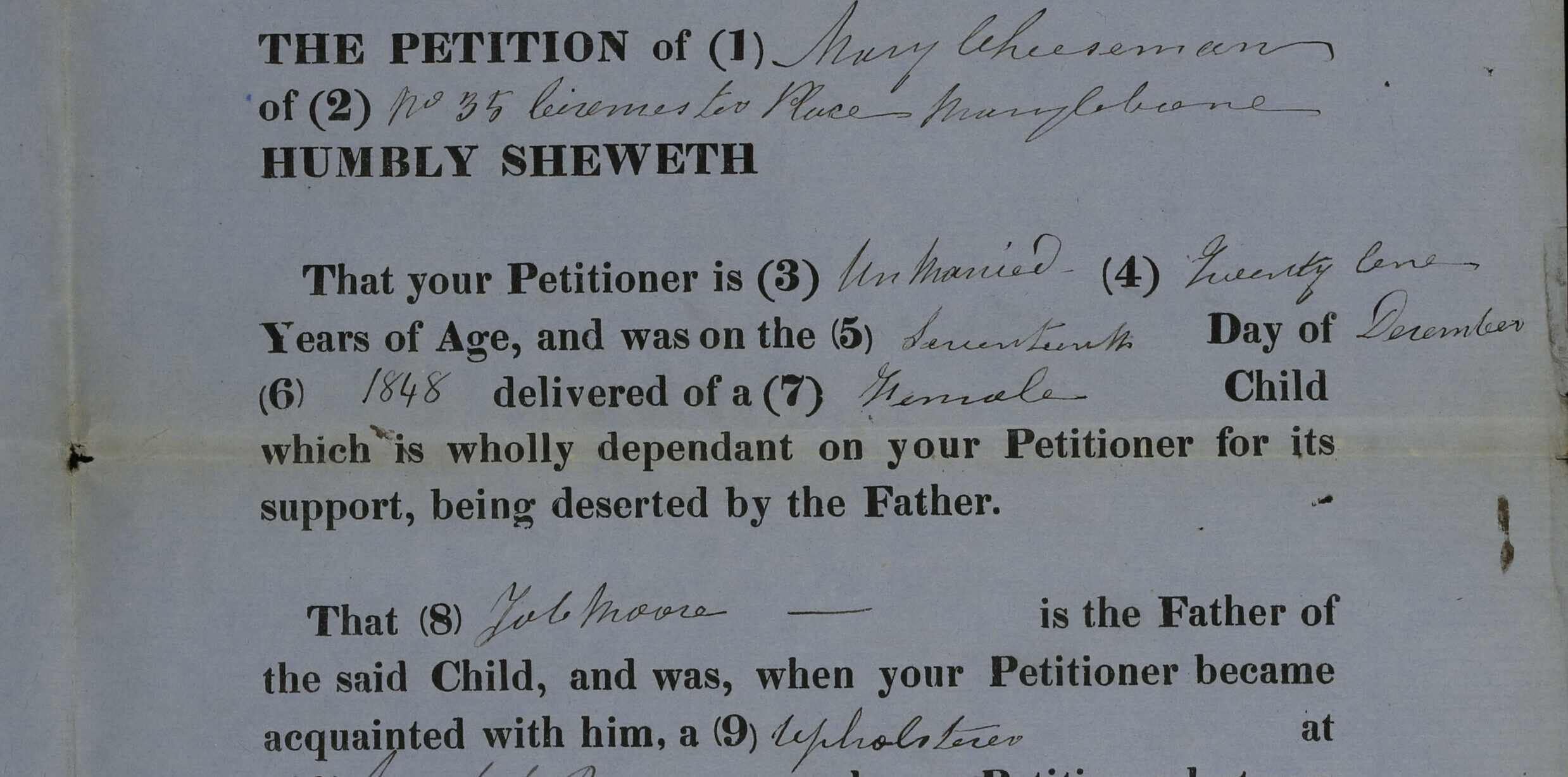

Mary’s story is a familiar one in Coram’s Foundling Hospital Archive. In 1847, she was working as a domestic servant for Mrs. Tymms of Maddox Street, Mayfair. There, she met Job Moore. He was an upholsterer laying carpets in the Tymms’s house. Job courted Mary, continuing to see her after his work there had ended. When they had known each other for three months, Mary received her employer’s permission to visit Windsor with him, having told Mrs. Tymms that Job had promised to marry her. It was in Windsor that their sexual relationship began. It continued until Mary told Job she was pregnant, only to discover that he was a married man.

The relationship ended, and Mary soon left her position with Mrs. Tymms to avoid her pregnancy being discovered. She initially went to live with an aunt in Wiltshire, and then returned to London, finding lodgings above a butcher’s shop. Here, aged 21, she gave birth to her daughter on 17 December 1848.

Only a month later, Mary was working for the Dickens family. After she left, she evidently struggled to find work to support herself and her child. On 26 May 1849, she was forced to petition the Foundling Hospital to admit her daughter. The Hospital interviewed Mrs. Tymms as part of their enquiries. Her glowing character reference described how Mary’s ‘modest demeanour was the subject of common observation in the house’ and emphasised that the admittance of the child ‘would save [her] from destruction’.

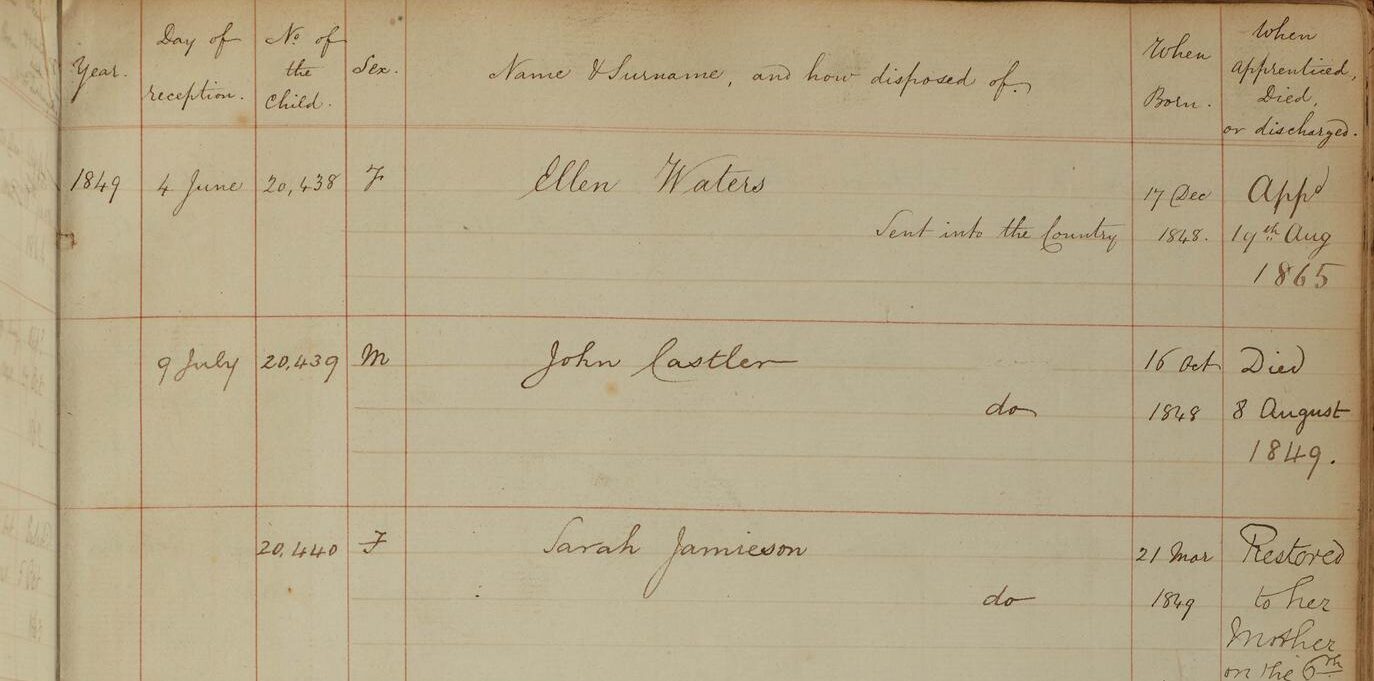

On 4 June 1849, Mary’s daughter was accepted into the Hospital, assigned the number 20438, and given a new name: Ellen Waters.

Ellen’s apprenticeships

We know little about Ellen’s life until the age of 16, when, on 19 August 1865, she was apprenticed as a domestic servant to Edward Johnson, a merchant in Egham, Surrey. Later, she was reassigned to the household of Walter Congreve, a schoolmaster from a land-owning family in Warwickshire, whose main residence was Sanremo, northern Italy. Sanremo was an established holiday and health resort that had attracted a significant expatriate community. Walter Congreve had moved there for the health of his first wife, but she died in 1865.

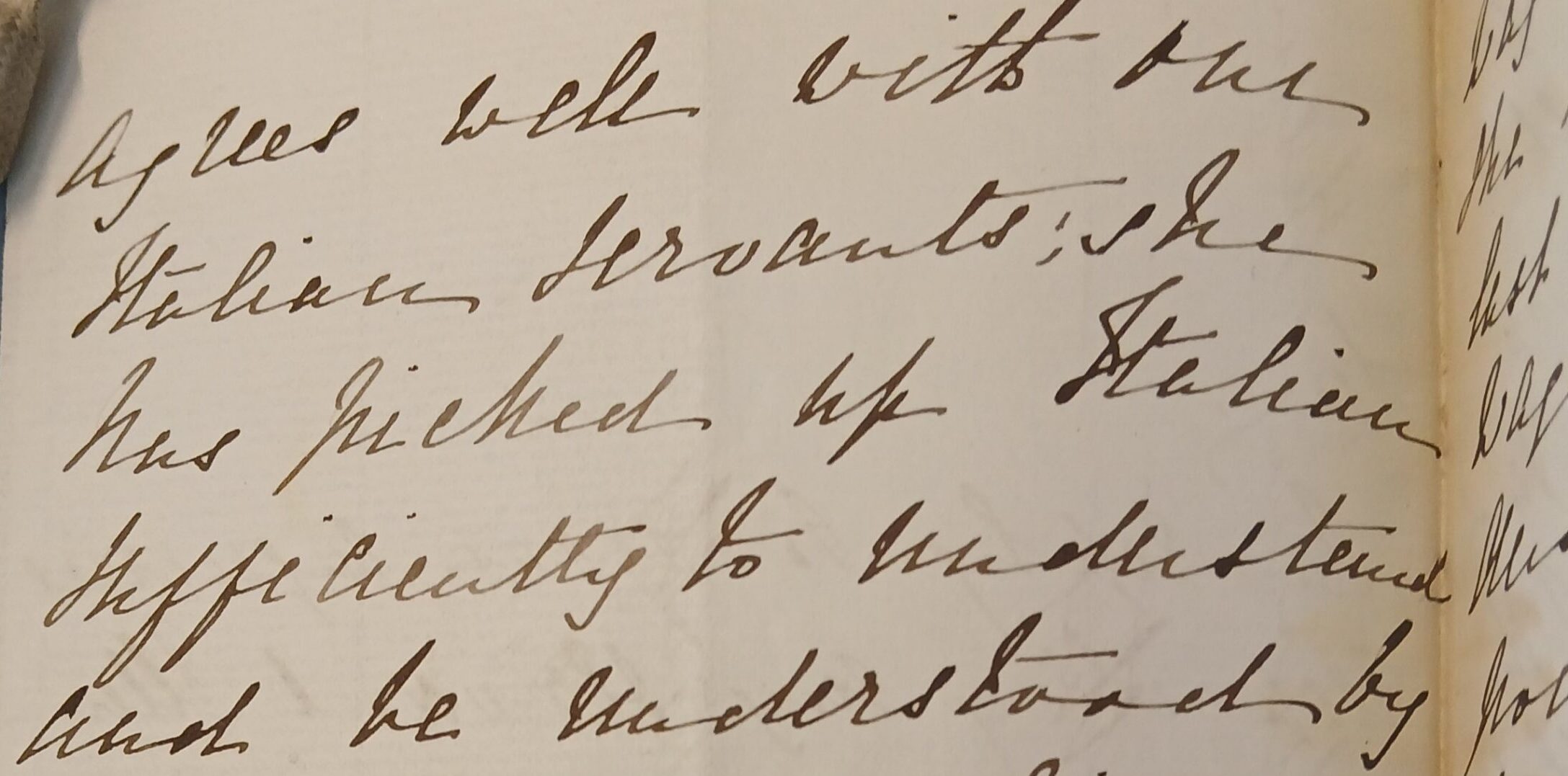

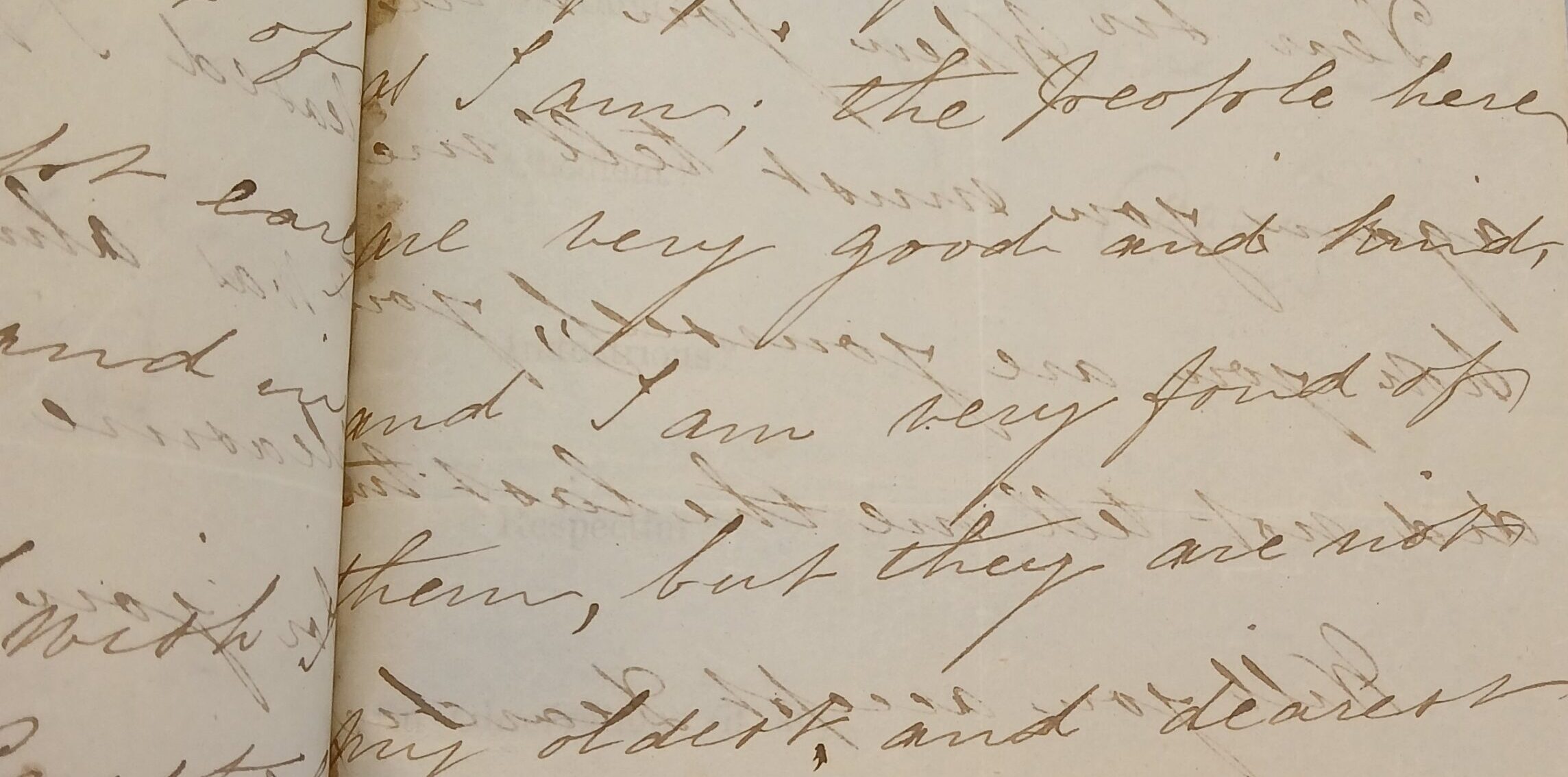

The Hospital requested yearly reports from Foundlings’ employers. Coram’s archive contains letters from 1868, in which Caroline, Walter’s second wife, reports on Ellen’s service. She described Ellen as ‘steady and respectable’ and ‘honest and obliging’. The family trusted her enough to leave her at the Italian villa while they spent the summer season in London. Caroline also commented on Ellen’s success in learning Italian (and some French) during her apprenticeship.

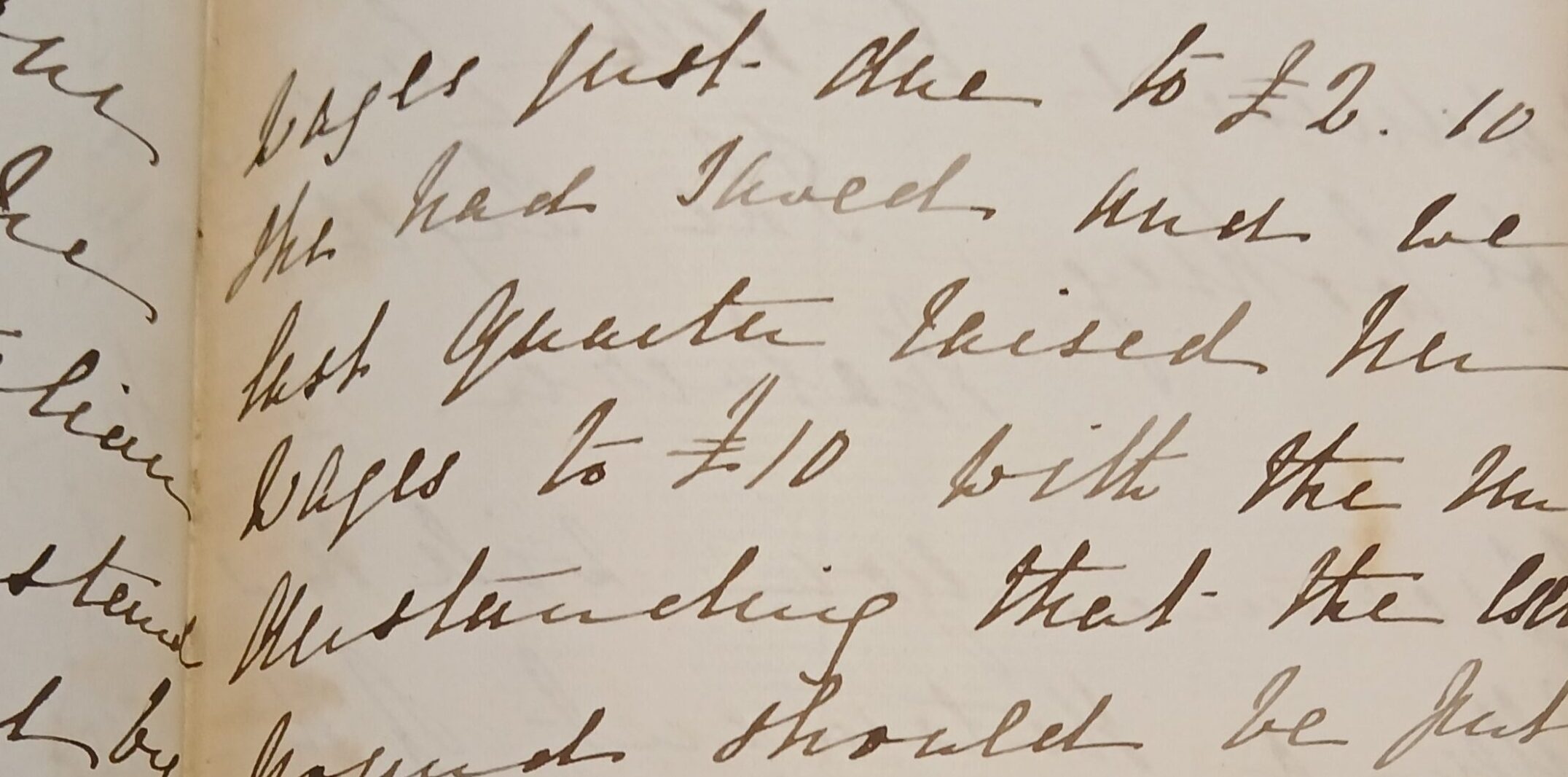

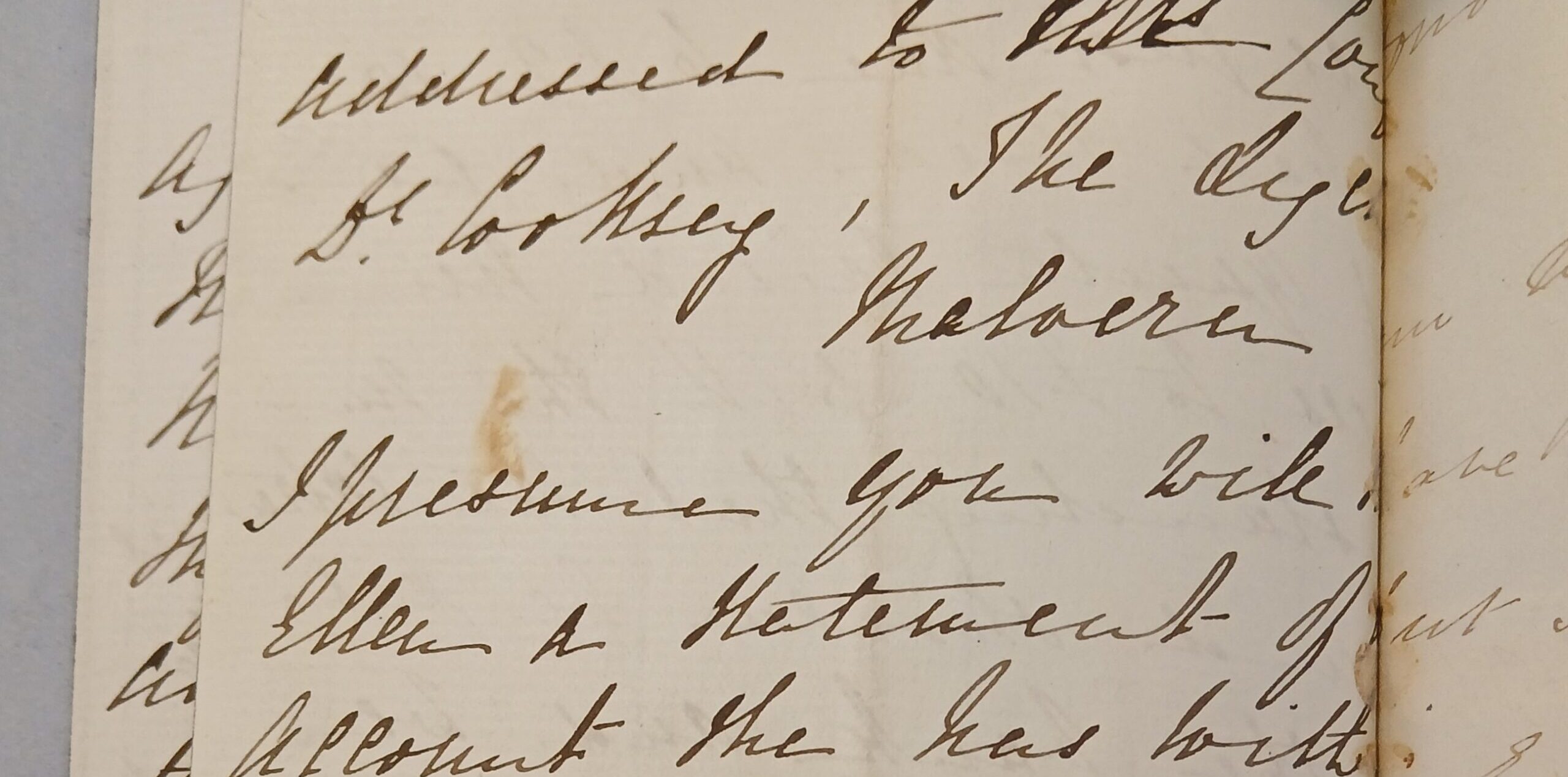

Moreover, the Congreves appear to have been attentive employers. They encouraged Ellen to save her money, raising her wages by a pound on the understanding that it would be put in a bank account that they set up for her while in London. Ellen also sent personal letters to staff at the Foundling Hospital at this time, in which she described being comfortable and happy with the ‘good and kind’ family she was working for. Ellen was awarded her gratuity payment in 1869 upon finishing her apprenticeship and remained in the service of the Congreve family.

Ellen’s relationships at the Hospital

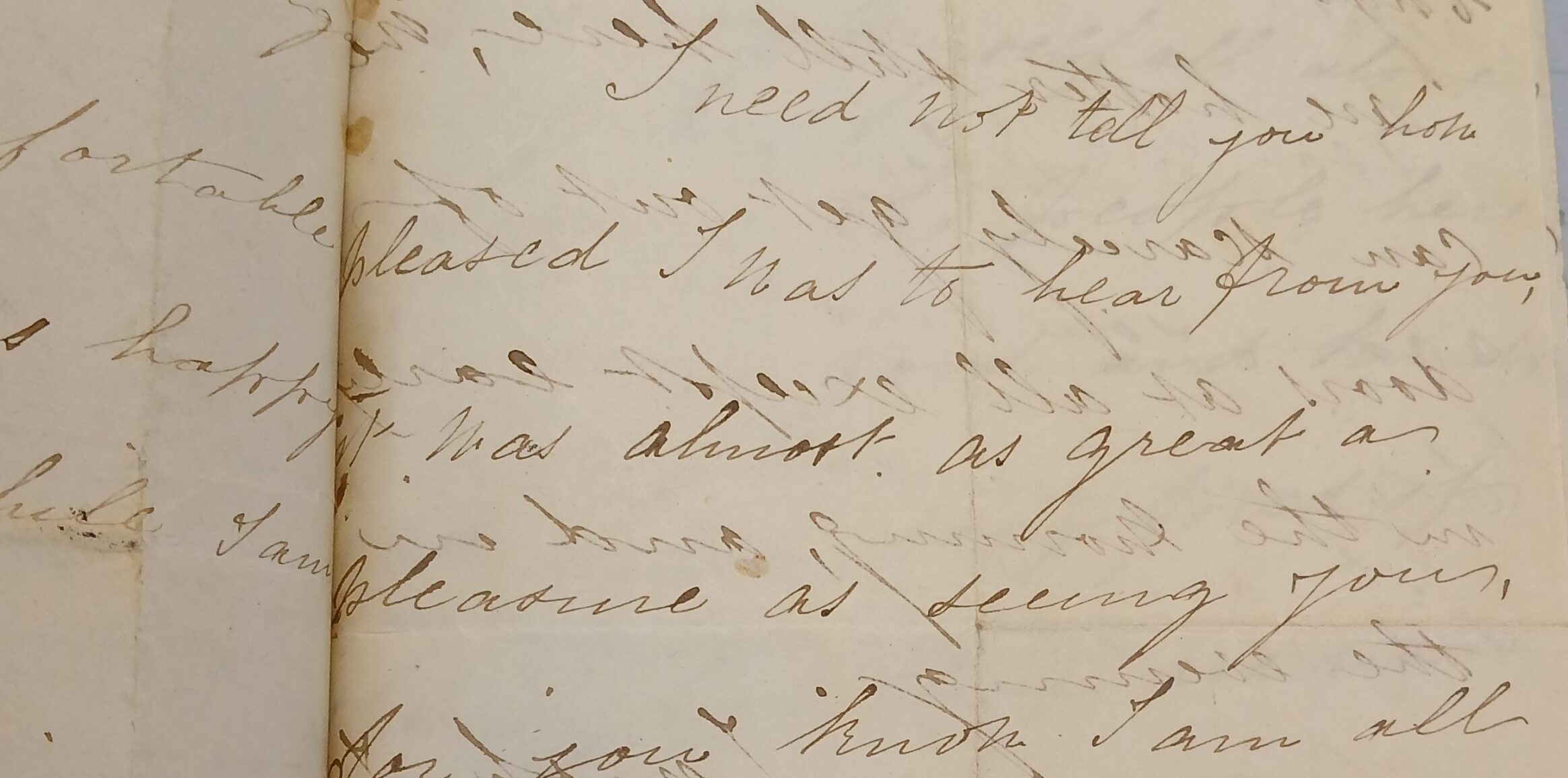

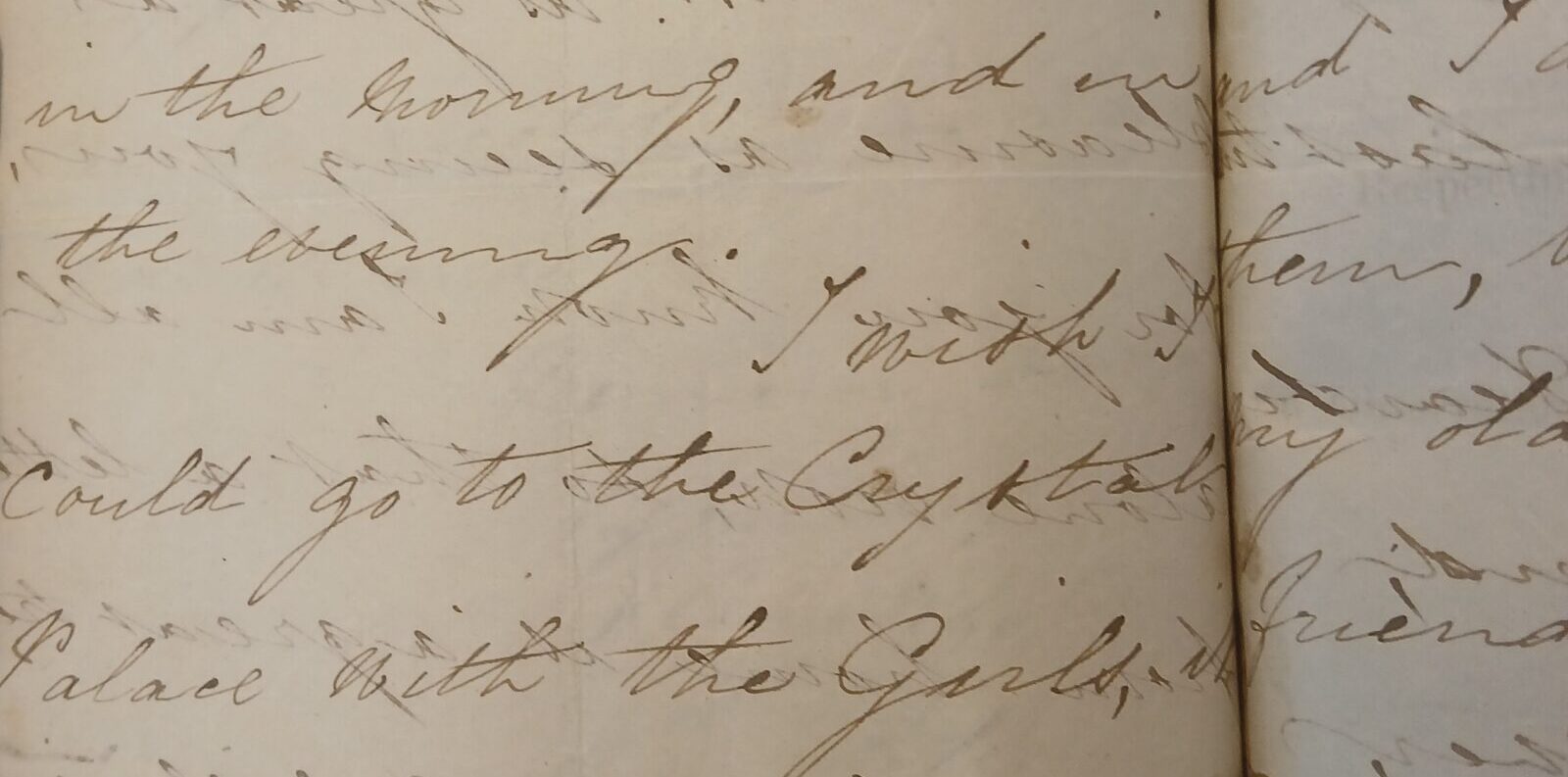

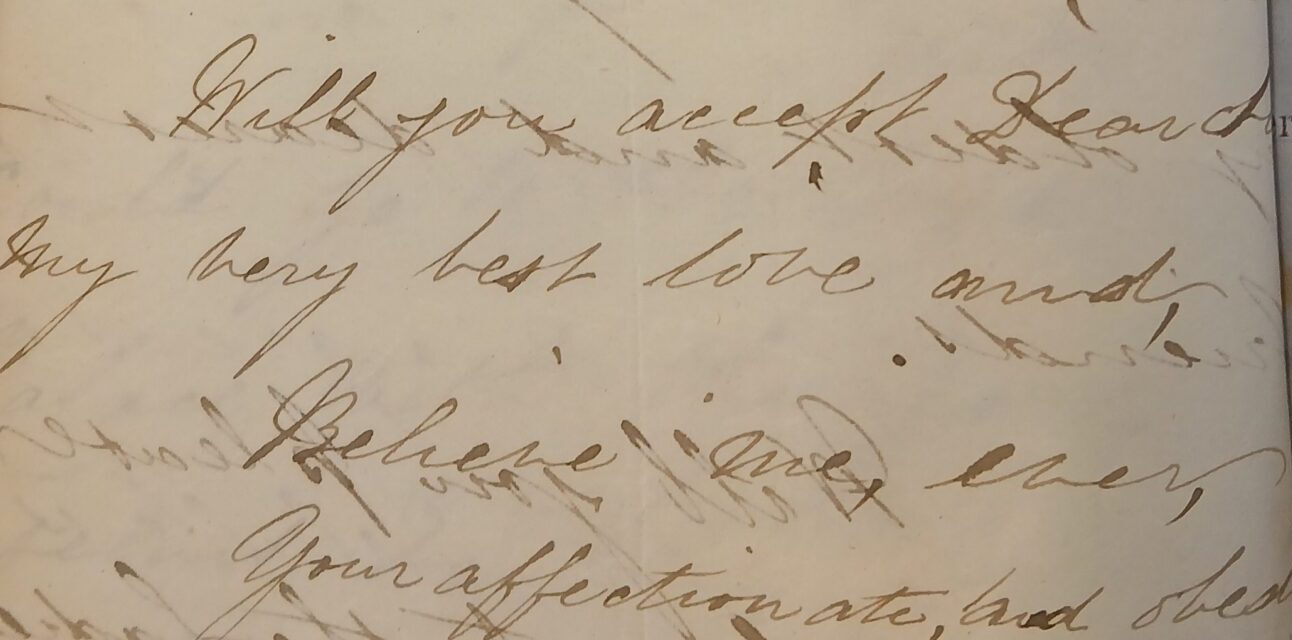

Ellen’s letters also express a real fondness for her time in the Hospital, and especially for the people she had left behind. In reply to the Secretary, John Brownlow, she wrote, ‘I need not tell you how pleased I was to hear from you, it was almost as great a pleasure as seeing you… a letter from home is a great treat’. She missed her friends at the Hospital, wishing to ‘go to the Crystal Palace with the Girls’. She said that, although she liked her fellow servants in Italy, they were ‘not my oldest and dearest friends’.

In his letters, John Brownlow seems to have updated Foundlings about their friends. One of Ellen’s responses reads, ‘So Ellen Delville is in Australia, farther from home even than I am; I wonder if she will be as home-sick as I was at first.’ The girls clearly had a mutual bond because around the same time, Ellen Delville wrote to Brownlow, ‘Will you give my love to Ellen Waters tell Her if she writes to me and sends me Her address I will answer by the 1st Mail’. In the very same letter, Ellen happens to mention that her mistress ‘has that work of Dickens “No Thoroughfare” – she is going to let me read it’.

A scandal in Italy

In the 1870s, another literary figure entered Ellen’s life. Writer and landscape artist Edward Lear lived next door to the Congreves in Sanremo. Walter’s sons appear in two of his paintings. Lear is now most famous for his nonsense poetry and for popularising the limerick.

His personal diaries reveal the next chapter in Ellen’s story. After the death of Caroline in 1870, Lear began to notice a relationship between Walter and Ellen. Then, in 1871, Ellen fell pregnant and left Sanremo. Lear recorded local rumours that Walter was the father, which were supported by the secrecy surrounding her departure. He wrote,

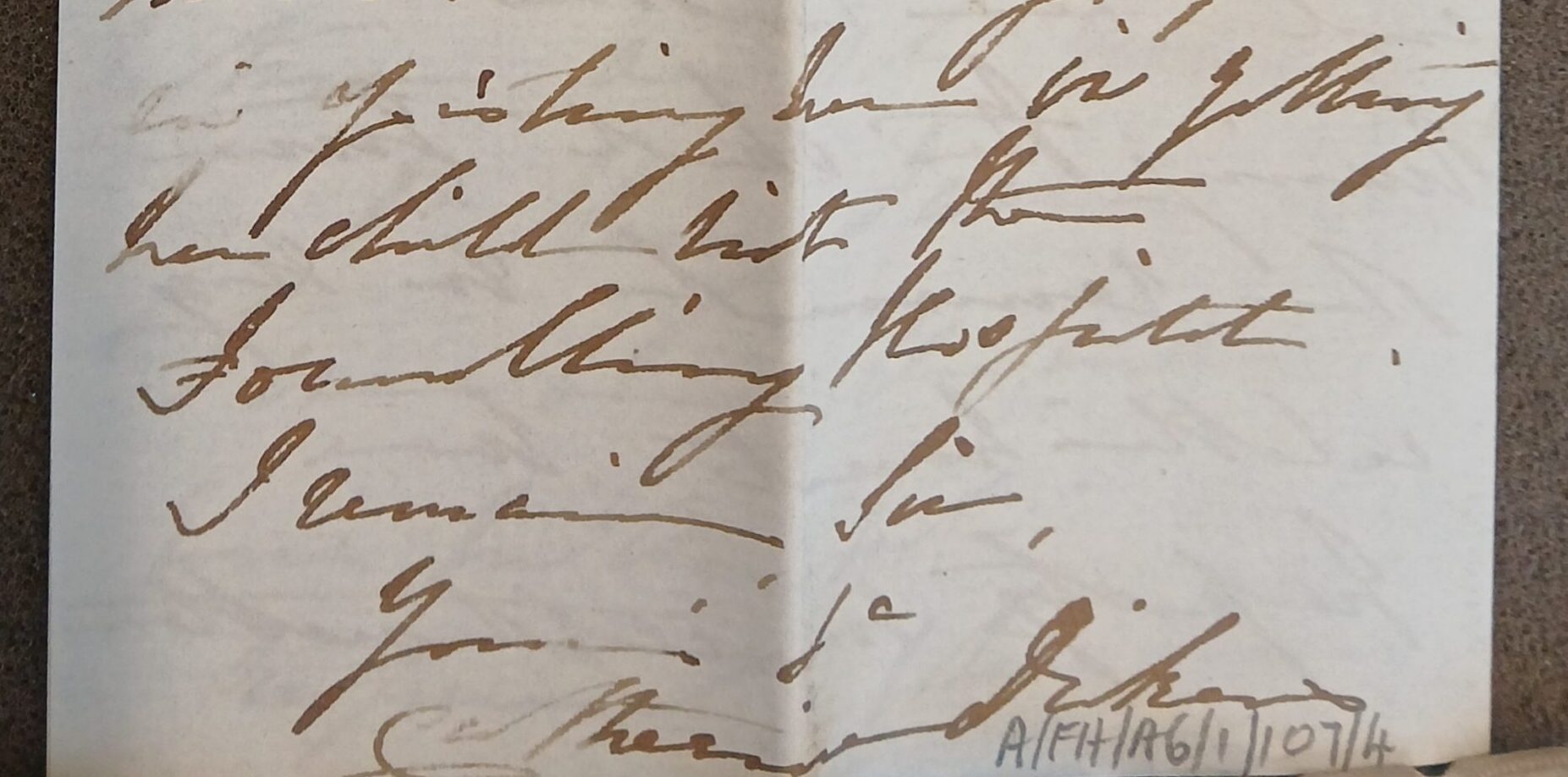

“Why maintain a perfect silence about the going away of a young woman who has been so valuable a servant for 4 or 5 years?”

Lear confronted Walter, who admitted to the affair, saying it was ‘a single fault & that he has never repeated it’. He was – somewhat reluctantly – considering marrying Ellen for the sake of her reputation, but Lear strongly discouraged this because of the risk to Walter’s sons’ reputations.

It has not been possible to trace Ellen’s story after her departure from Sanremo. We know that she did not petition the Foundling Hospital to take her illegitimate child. She and Walter must have maintained contact, though.

In 1878 Lear learned that Walter was planning to move a few miles along the Italian coast to Alassio. He would be living with his son Arnold, nephew John, and Ellen Waters. The scandal resurfaced. One of Lear’s acquaintances called Walter ‘a damned fool, to be keeping that woman … because he had a child by her 7 years ago!’

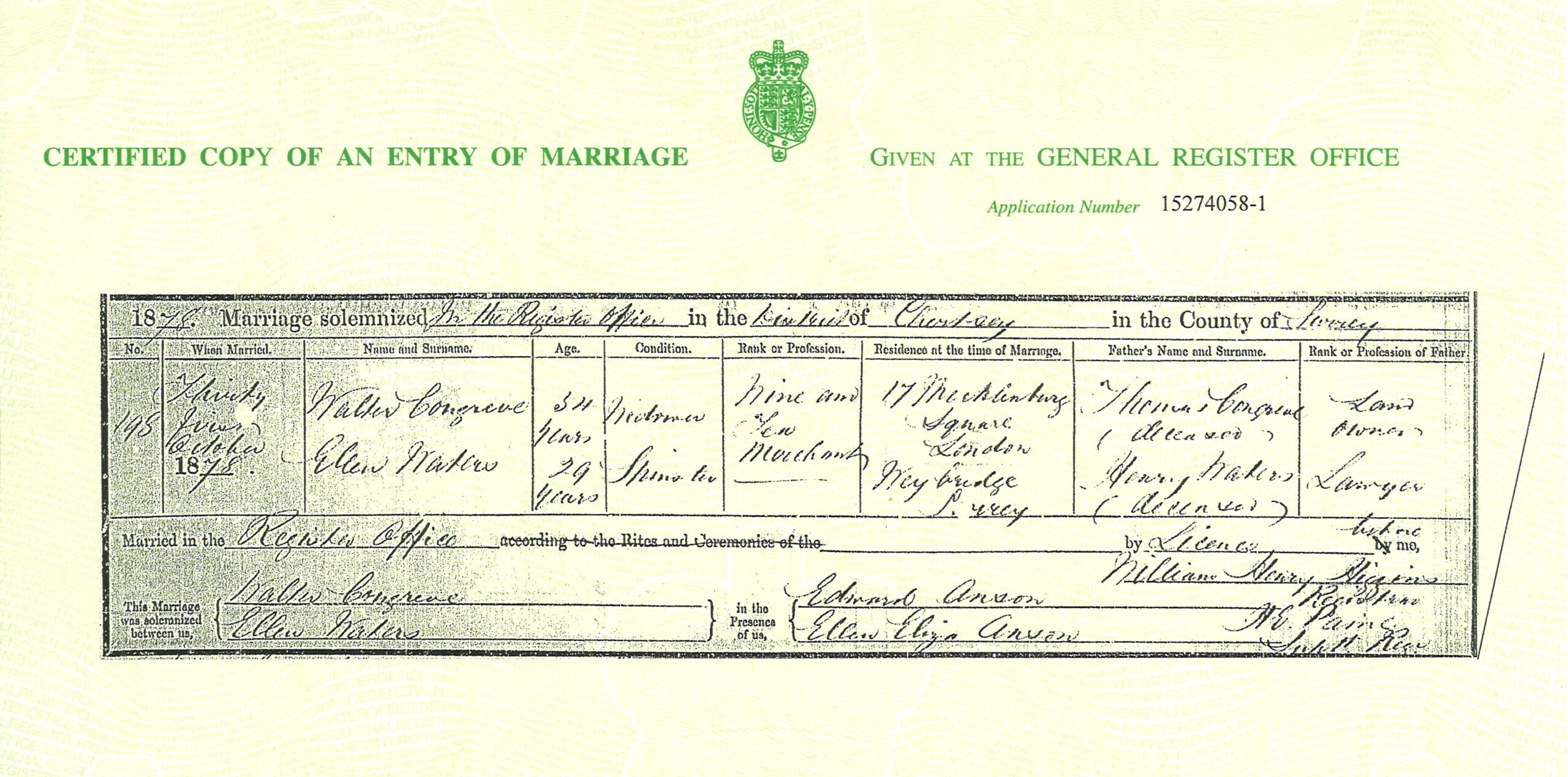

In October 1878, Ellen and Walter were married in England. Interestingly, Ellen chose to invent a father – a deceased lawyer called Henry Waters – on her marriage certificate rather than admit to being illegitimate. Lear was outraged at the marriage, mainly on behalf of Walter’s sons, and the friendship ended.

Ellen and Walter lived in Alassio for the remainder of their lives. In December 1879, their daughter Julia Maria was born and possibly later, a son named Richard. Walter died in 1913, aged 88, and Ellen in 1936, also aged 88.

You can view a gallery of images of the letters and documents below. Click on the images to expand the documents.