Content warning: This article contains reference to sexual assault which readers may find distressing. Find more information on our help and support signposting page.

Of the 27,000 children admitted to the Foundling Hospital in its 200 years of existence, only around 3% were claimed by their mothers. The Foundling Hospital Archive details those who were claimed, who claimed them, and when. One of those fortunate children was Elizabeth Puxty, and her case was an unusual one.

The Foundling Hospital’s purpose

The Foundling Hospital was founded by Captain Thomas Coram in 1739 to lessen the number of babies abandoned on the streets by mothers who could not care for them. He aimed for the Hospital to play a role in caring for these children and provide them with the ability to contribute to society positively.

Thomas Coram hoped that the Foundling Hospital would be viewed as a short-term reprieve for struggling mothers, where they might leave their babies in capable hands. In the ideal scenario, the mother would use the time to improve her situation so that she would be able to look after her child.

In the first two decades of the Hospital’s operation, when a baby had passed all the medical tests and the mother’s appeal was approved by the committee, she was encouraged to leave a token with her child, such as a button, piece of ribbon, or playing card – anything that could aid in identifying her child. This token and meticulous records kept by the Hospital would be used in the future should the mother return and ‘claim’ her child.

Elizabeth’s life at the Foundling Hospital

On 12 October 1750, a baby girl was admitted to the Foundling Hospital and assigned the number 648. She was admitted under the ballot system when she successfully passed the health inspection.

In the ballot system, mothers had to select a ball from a bag. The colour of the ball determined their child’s admission result. White meant the baby was confirmed a place if they passed the health check, orange meant they were on a waiting list, and black meant they would not be admitted. Elizabeth’s mother selected a white ball.

The Foundlings were baptised following their admission and renamed to erase any link to their mothers. Foundling 648 was one of 20 foundlings baptised in the Hospital Chapel. Therefore, from 14 October 1750, just two days after her admission, Foundling 648 was known as Elizabeth Puxty.

Elizabeth was immediately assigned to a wet nurse, Mary Hedges, in Uxbridge. Nurses were hand-picked by the Foundling Hospital’s committee and provided with a good salary during the duration of the Foundling’s stay.

On 29 November 1754, Elizabeth left Mary and returned to the Hospital to start her schooling. Reading was introduced as a subject of study for both boys and girls in 1757, the year the Governors chose the first official schoolmaster. However, the decision to include reading in the curriculum for girls was viewed as controversial.

Once the Foundlings were old enough, they were apprenticed. These apprenticeships allowed the Foundlings to find employment and contribute to society when they left the Hospital. According to Elizabeth’s records, in July 1759 she was apprenticed to the jeweller Collin Chissolm in the parish of St Ann’s in Westminster, London. She was to be employed in domestic service until she was 21 or got married.

Elizabeth’s apprenticeship

Elizabeth left the security of the Foundling Hospital to begin her apprenticeship. Things did not, however, go as well as the Hospital had intended. Elizabeth was ‘enticed’ away from her master in January 1762 by a man named Bray Brouncker, who raped her. Collin Chissolm, her master, reported Brouncker, who was later imprisoned. According to the Middlesex session rolls, Chissolm testified that Brouncker was aware of Elizabeth’s age: 11 years old. Brouncker was imprisoned in Clerkenwell Bridewell, where he wrote to the Foundling Hospital, declaring his intention to marry her.

Elizabeth was withdrawn from Chissolm’s care as soon as Brouncker’s actions came to light. Chissolm paid a Mrs Frowde £3 to cover the cost of caring for Elizabeth while she was still legally his responsibility. When appearing before the Committee, accompanied by Mrs Frowde, Elizabeth expressed reluctance to return to Chissolm. A decision was reached to force Chissolm to cancel her apprenticeship and have Mrs. Frowde continue to care for Elizabeth in her home. The Foundling Hospital paid her 3 shillings per week for Elizabeth’s expenses and provided new clothes for Elizabeth.

Now, Elizabeth needed a new employer because her apprenticeship had been cancelled. Her former nurse, Mary Hedges, and her husband Stephen, volunteered to take Elizabeth. While the Committee conducted a background check on the Hedges, Elizabeth returned to the Hospital in May 1762 for a short period before her journey to Uxbridge to begin her new apprenticeship. Elizabeth Puxty’s narrative, however, was far from over.

On 24 March 1764, the Committee discussed a letter written by Mrs Anne Hildesley of Uxbridge requesting that Elizabeth Puxty be removed from her care because Elizabeth had committed theft. The Committee did not want Elizabeth to return to the Hospital for fear of setting a bad example for the other Foundlings. Therefore, Mrs. Hildesley was requested to keep her until the Committee could find another solution.

However, Elizabeth was fortunate because, while the Foundling Hospital was unsure what to do with her, someone came to the Hospital asking for her.

Elizabeth’s claiming

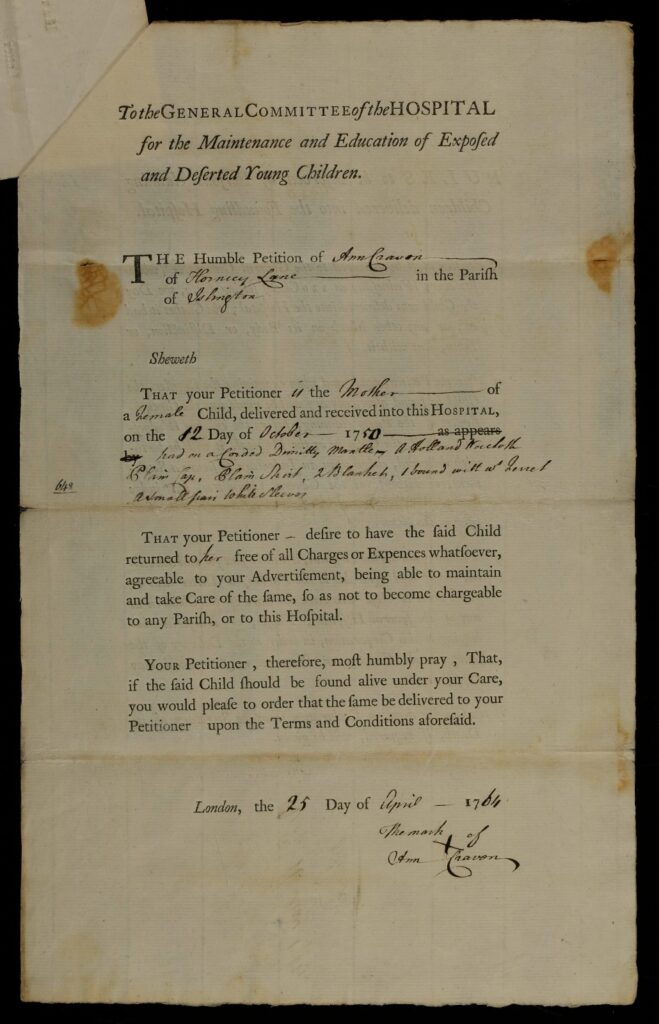

On 16 May 1764, Ann Craven of Hornsey Lane, Islington, came to the Foundling Hospital to claim her child. Fourteen years previously, she had arrived at the Hospital to admit her daughter, and now she returned, over a decade later, to reclaim her.

Petitions Claiming Children A/FH/A/11/002/005/045/a1

The Governors carried out the standard regulatory checks to verify whether Ann was Elizabeth’s biological mother. What is astonishing is that Ann was able to meticulously describe various items of clothing Elizabeth had been wearing when handed into the Hospital. Ann’s description matched the list of clothing recorded on Elizabeth’s billet sheet in 1750. Thus, the General Committee ordered that Elizabeth was to be delivered to Ann, and she was given permission to take her daughter home.

What made Elizabeth’s case unique, even among the other claimed Foundlings, was that her mother came back for her after 14 years. Typically, if children were not claimed within five years of admission, it was believed that they would remain at the Hospital until they were apprenticed. The number of cases where children were claimed after age six was extremely low, and Elizabeth was one of the few foundlings claimed after age 10.

There is very limited information that we can gather from the archive about Elizabeth’s mother, other than the fact she was widowed when she came to claim Elizabeth. Ann did not submit a petition letter in 1750 because Elizabeth was admitted through the ballot system and as per the Foundling Hospital’s policies, the mother’s identities were kept secret. Therefore, we are unable to determine Ann’s actual circumstances, which caused her to leave Elizabeth in the Hospital.

However, Ann clearly always remembered the child she left in the Foundling Hospital in 1750 and had returned to claim her despite being widowed. It implies that she still had a deep emotional attachment to her child and was prepared to deal with any criticism that living with her grown daughter would have elicited from her neighbours and acquaintances.

Happy ending?

Little is known about Elizabeth after she was claimed, until 1776, when she married Robert Barham on 8 October at St. Michaels and All Angels Church in Sandhurst, Kent. Between 1777 and 1791, the couple had six children: two daughters and four sons. Elizabeth passed away at the age of 77 and was buried at Sandhurst on 1 November 1827.

Special thanks to Phil Long, Elizabeth’s 4x great-grandson, for providing details of Elizabeth’s life after she left the Foundling Hospital’s care.

Bibliography

Foundling Hospital Archive

General register: A/FH/A/09/002/001/071

Baptism register: A/FH/A/14/004/001/049

Apprenticeship register:

A/FH/A/12/003/001/044

A/FH/A/12/003/001/343

Claimed register: A/FH/A/11/001/013

Petitions claiming children: A/FH/A/11/002/005/045 (includes billet sheet)

Sub-committee minutes:

A/FH/A/03/005/005/011

A/FH/A/03/005/005/013

A/FH/A/03/005/005/018

A/FH/A/03/005/005/025

A/FH/A/03/005/005/061

A/FH/A/03/005/005/078

A/FH/A/03/005/005/080-81

A/FH/A/03/005/005/090

A/FH/A/03/005/005/259

Other sources used

Bray Bronnker Indictment Number 22, Sessions Roll for the Middlesex Sessions of the Peace for the Month of February 1762, London Metropolitan Archives, ref: MJ/SR/3124

Clark, Gillian, and Bright, Janette. 2015. ‘The Foundling Hospital and its token system’. Family & Community History, vol.18, issue 1, pp53-68. DOI: 10.1179/1463118015Z.00000000039

Copyright © Coram. Coram licenses the text of this article under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 (CC BY-NC).