Each baby left in the Foundling Hospital’s care was given a new name in order to provide anonymity for both mother and child. However, the Hospital made it possible for mothers to reclaim their babies if their circumstances changed. In the 18th century, one of the ways the Hospital could re-establish the link between mother and child was through tokens.

Leaving a token

On the day a child was admitted to the Founding Hospital, staff filled out a billet. This recorded identifying information, such as gender, the clothes the child was wearing, and any distinguishing marks on the body. The billet did not record the child’s name.

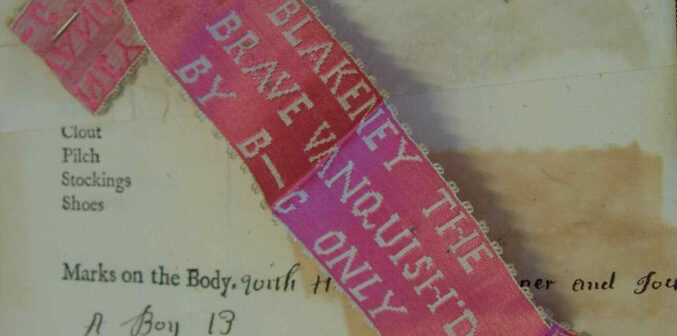

In addition, the Hospital encouraged mothers to supply a ‘token’, a small identifying item such as a ribbon, a rosette, a button, or a coin. The billet sheet was folded around the token, sealing it within a little package, and stored safely away at the Hospital. If the child was ever claimed, the billet would be opened and the token used as a method of confirming the identity of the child. The mother could either describe the token or produce a matching part of it. The children who were not claimed never learned if a token had been left for them.

Types of tokens

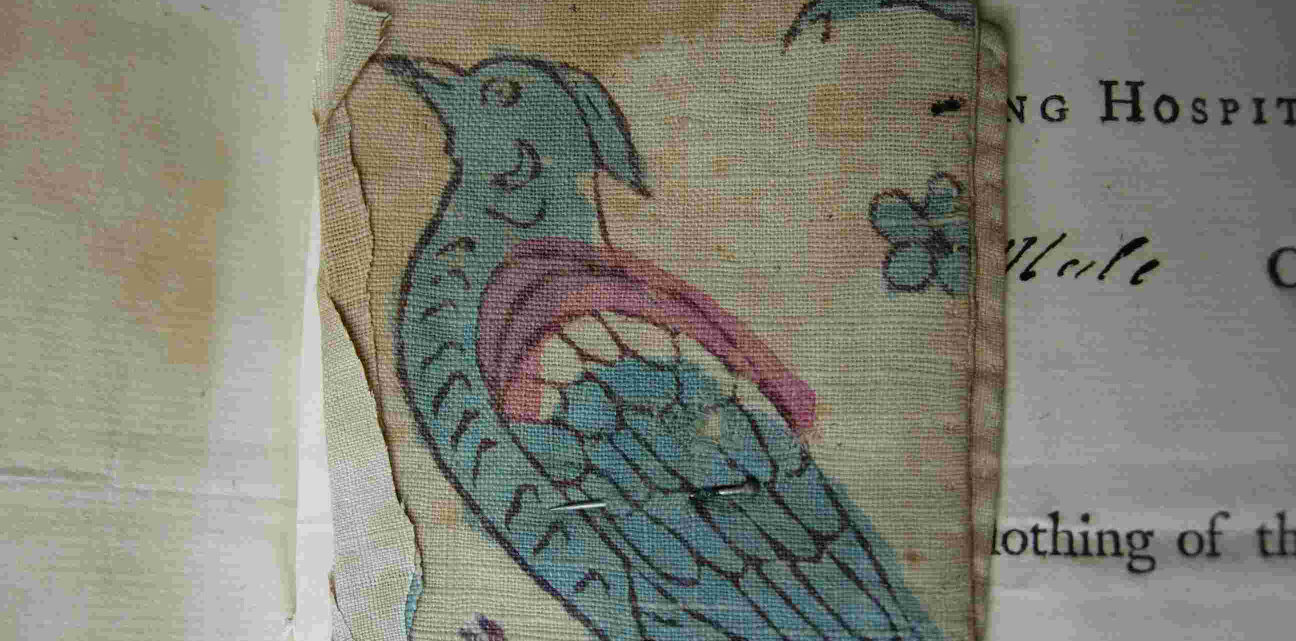

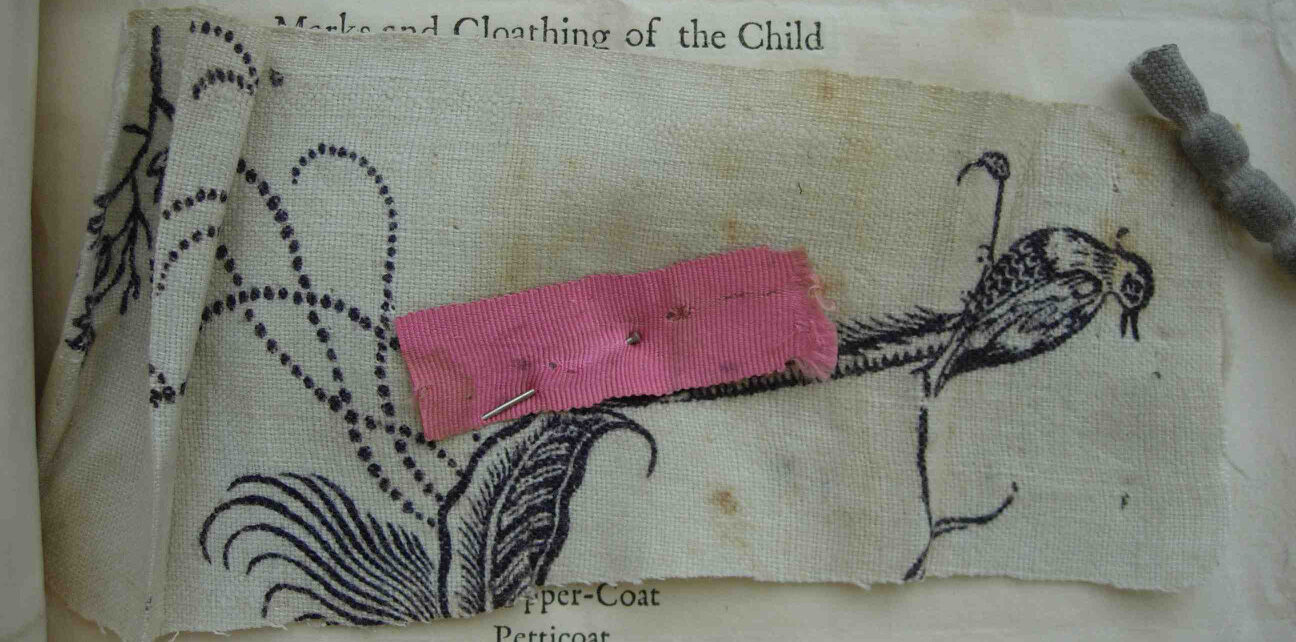

Most women in the 18th century were illiterate, and so material literacy – where certain objects were used to mark events, express allegiances, and forge relationships – was a familiar and accessible way for mothers to express the hopes they invested in their babies. Leaving a piece of fabric decorated with an acorn or a bud might suggest new growth, a bird or a butterfly the chance to fly free, a flower the capacity to blossom and bear fruit.

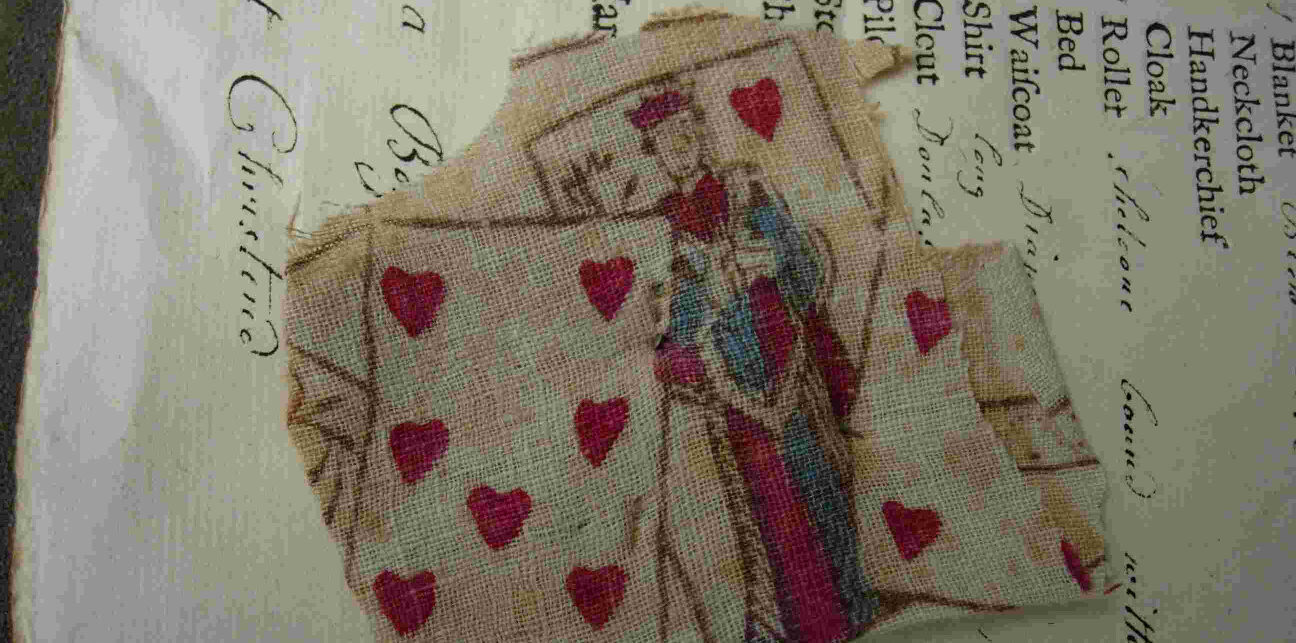

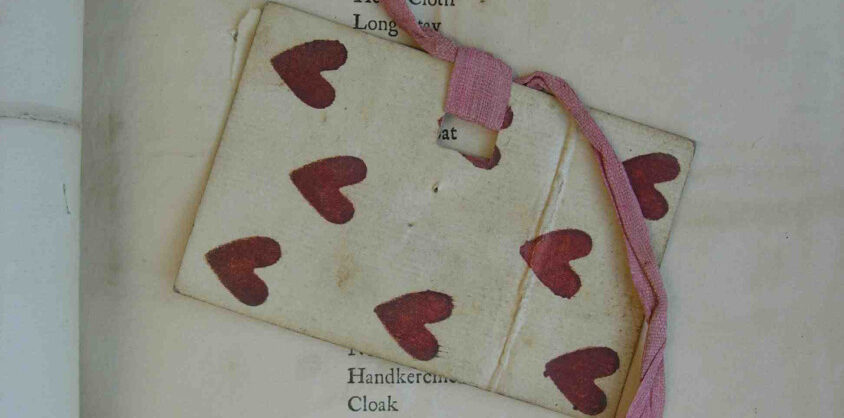

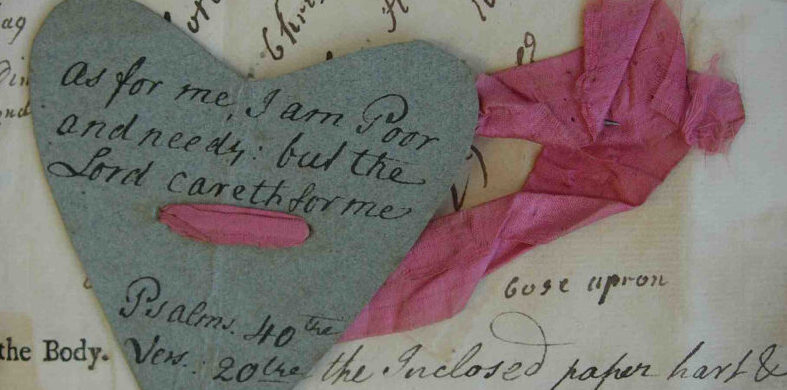

Ribbons were common courting gifts and may have been left by mothers as a representation of the strong bond she had with the child. Hearts, by then a well-established symbol of love, were embroidered onto fabric, cut out of paper or fabric, or left in the form of a playing card in the suit of hearts.

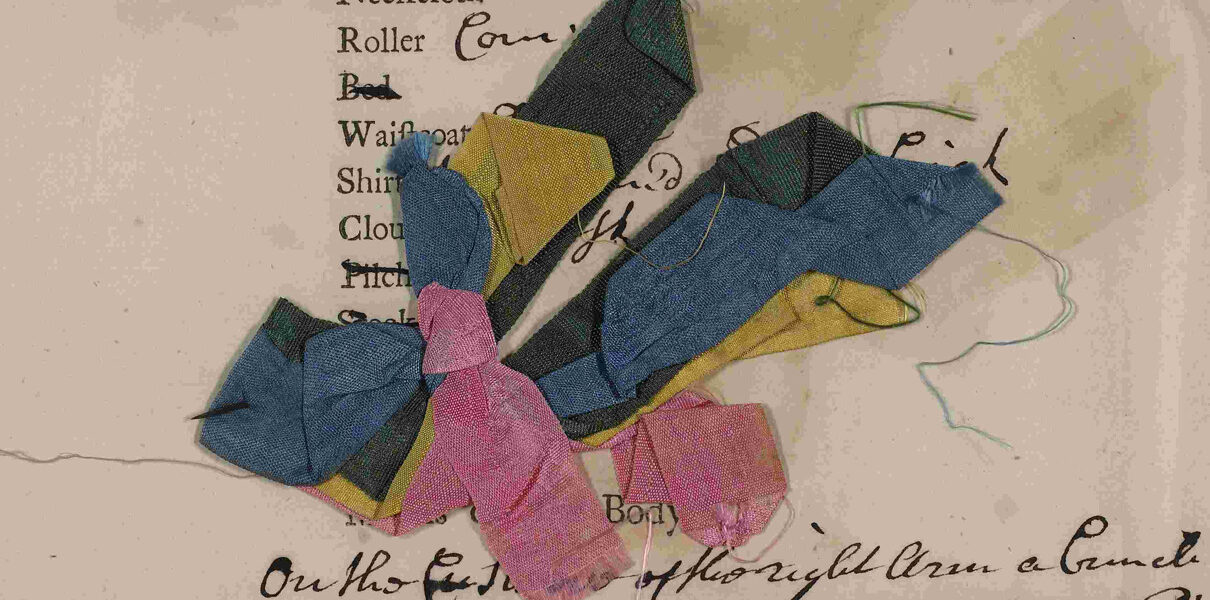

While pieces of fabric had been used as tokens in earlier years, from June 1758, at the start of the General Reception period, Hospital staff began cutting two-inch squares of fabric out of other pieces of material to act as tokens. During the General Reception, the Hospital was legally required to admit every child brought to its door. Hundreds arrived every month, and the Hospital had to have a means of distinguishing them. Pieces of infants’ clothing, such as sleeves, and corners of blankets were also used as makeshift tokens. The fabric tokens in Coram’s Foundling Hospital Archive amount to around 5,000 individual items, making it the largest collection of everyday 18th century textiles in Britain today. The majority date from 1758 to 1764.

Handwritten notes

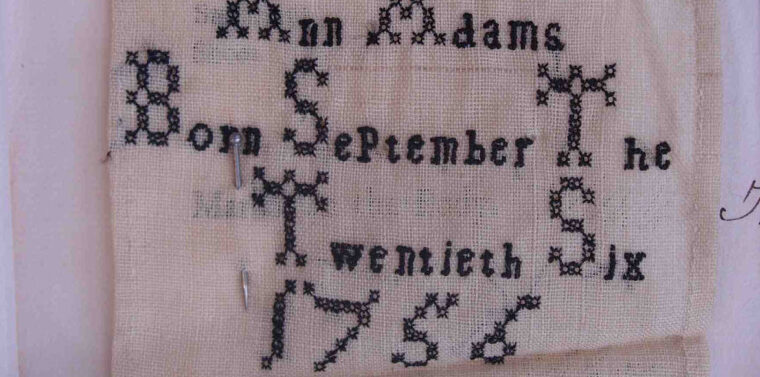

Those mothers who could write (or had someone to write for them) often attached a note to the child’s wrist or clothing. These handwritten notes outnumber the tokens and were most prevalent between 1756 and 1770. At their most rudimentary, the notes simply state the child’s basic details (original name, date of birth, or whether christened or not). But many go further, explaining the circumstances of the child’s birth, or expressing a wish to reclaim the child in the future.

These notes are where the most direct expressions of maternal emotion can be found. Foundling 8338, for instance, was admitted in May 1758 with a ribbon embroidered ‘Philip Hollond’ (the Hospital re-named him Mark Jessop). An accompanying handwritten poem reads:

‘Go gentle Babe! thy future hours be spent / In Vertuous purity and calm content. / Life’s sunshine Bless thee; and no anxious care / Sit on thy Brow, and draw the falling tear’.

The tokens today

The introduction of a petition system in 1768 rendered the tokens unnecessary for claiming children because mothers had to write a petition letter to the Hospital requesting the admission of their child. The Hospital investigated their cases before the child was admitted, and this created a record that could be referred to if a child was claimed.

In the mid 19th century, Hospital staff opened all the billets. The ‘soft’ tokens – those made of fabric or paper – were pinned to the unfolded billet sheets, along with any handwritten notes. The billet sheets were then bound into volumes, and these Billet Books are now an important part of Coram’s Foundling Hospital Archive. The ‘solid’ tokens (small objects made of metal, bone, or wood) were exhibited in the Foundling Hospital’s own museum in the 19th and 20th centuries. They are now owned by the Foundling Museum, where many of them are on display.

View an image gallery of some of the tokens below.