In the late 1750s and early 1760s the Foundling Hospital in London had a significant problem. Very large numbers of children had been taken in during the period of the General Reception (1756-1760) and, as these children aged, the institution was struggling to find accommodation and carers for them all. The solution was to set up six branch hospitals around the country. The one in Chester was the last to be established.

Setting up the Hospital

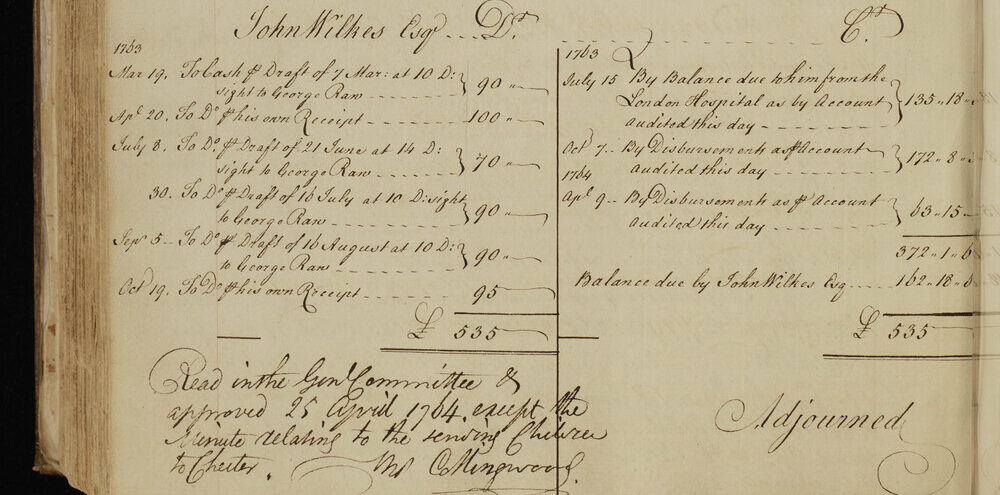

Between 1763 and 1769, 306 children came through the Chester hospital’s doors, all starting their care journey in London (none were directly admitted from Chester itself). Chester was probably chosen because the London hospital’s Treasurer, Taylor White, was a judge on the region’s court circuit and would have known the city and its leaders well. Chester also met a number of general criteria for branch hospitals: it had a reputation for being a healthy place to live and had a relatively low cost of living. Fuel, needed to warm the hospital’s wards, was in plentiful supply from nearby coal mines. There were also plenty of opportunities for useful work for the children during and after their period of care.

The city elders were honoured that Chester had been chosen as a venue for a branch hospital; they felt it reflected well on the place. The local people were less enthusiastic. In an echo of today’s attitudes by some towards asylum seekers, they were concerned that the costs of maintaining these needy children from London would fall on local people. Locals had to be physically shown the relevant Act of Parliament to convince them that it was worded to ensure that no financial burden could fall on them.

The Chester hospital was situated in a fine building, the Blue Coat School, which had housed a school for poor local children since 1717 but was apparently unoccupied in 1763. The initial intention was that it would house 40 Foundlings. Meanwhile, plans were drawn up for the construction of a much larger building on a site just south of the city, to accommodate 400-500 children, but this never got off the drawing board. The London governors told the Chester governors and staff to call their institution an ‘Orphan Hospital’ because the word foundling ‘may be used as a name of reproach to the children, as supposing them all illegitimate which [they] certainly are not’.*

The children

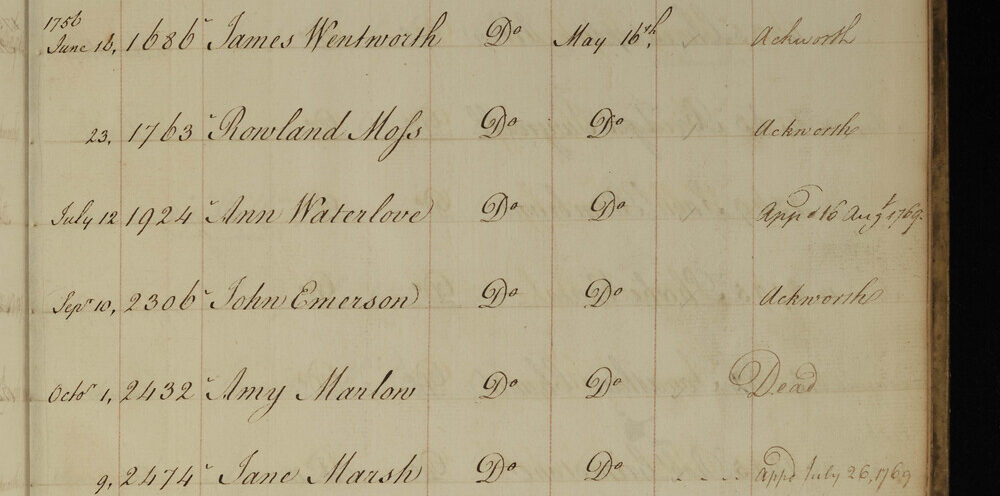

The first children to arrive in May 1763 were transferred from the Shrewsbury branch hospital. Most of the later arrivals came from London – a nine-day coach journey. They comprised a mix of orphans, those who were illegitimate, and those whose mothers simply could not cope. Married couples would also surrender their child; single-parent status was not a given. A few of the Chester children – such as Mary Sanderson (No. 12949) and Charles Rouse (No. 12991) – were one of pairs of twins, separated in London, who would never know they had a sibling. Just one child, James Wentworth (No. 1686), has so far been identified as being a true ‘Foundling’: he was discovered by a stranger after being abandoned.

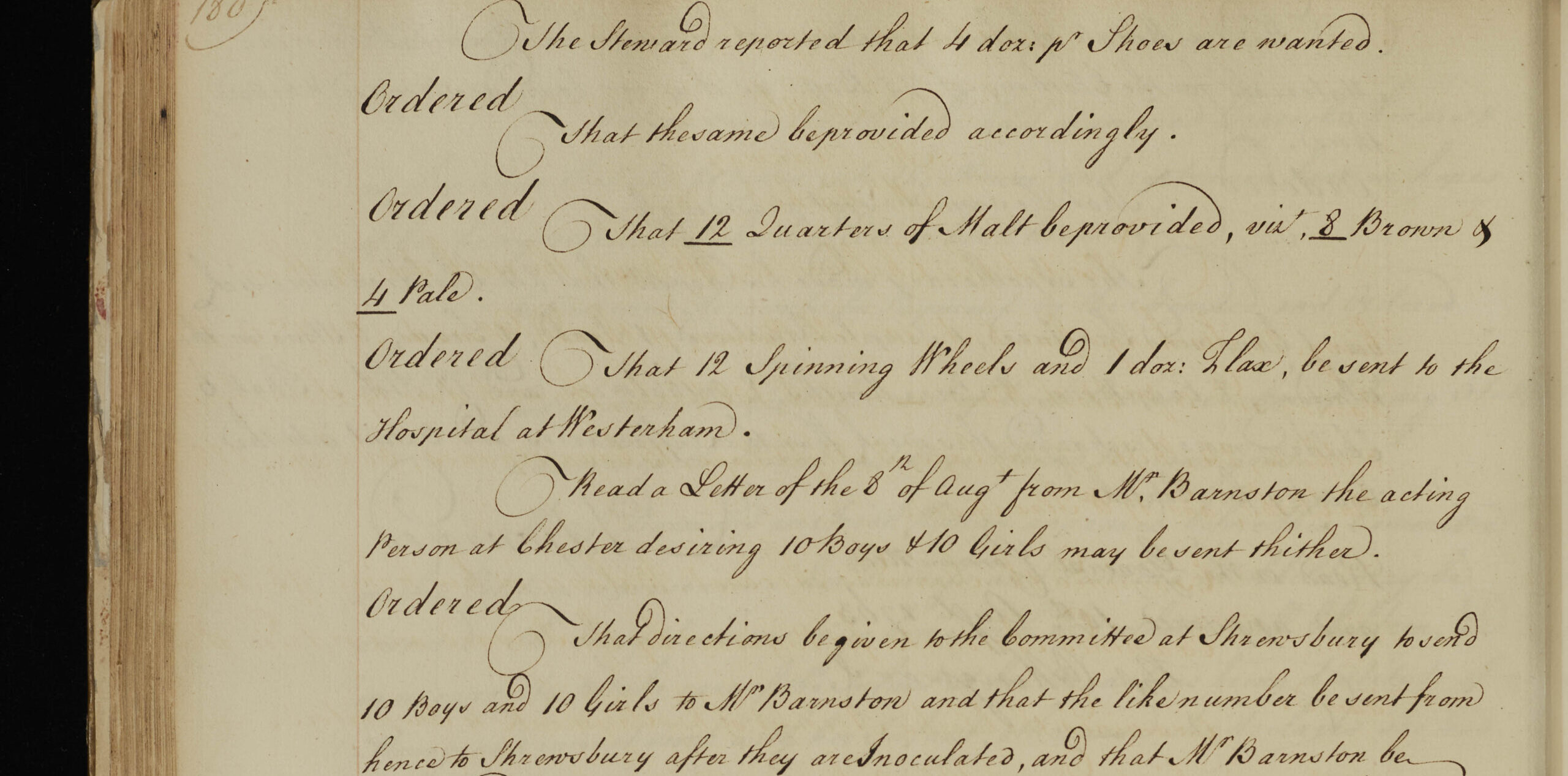

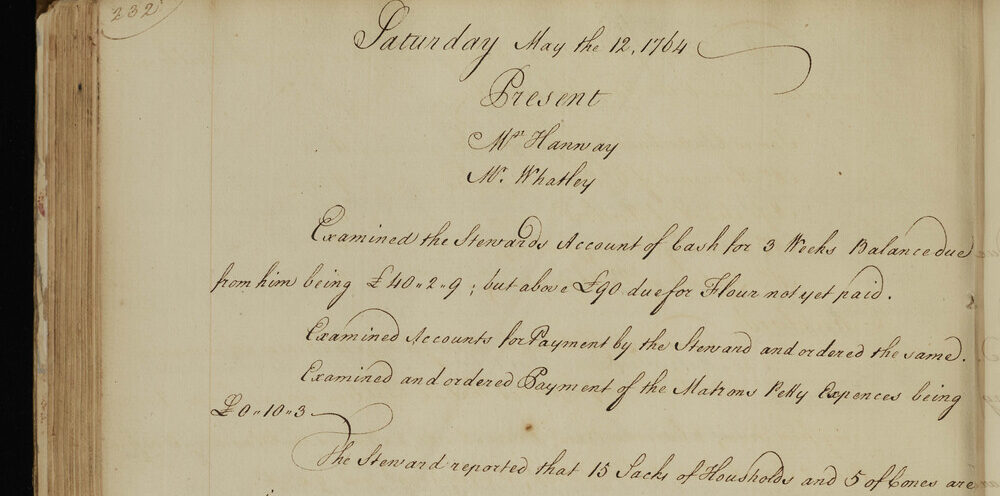

The number in the Blue Coat building swelled to 71. London wanted to send even more children, but the Chester governors kept complaining about the already uncomfortably large number for the available space. However, after the initial arrivals, most of the children who arrived at Chester were quickly sent to live with nurses – paid carers who were mostly female but, in a few cases, male. This was necessary because of the very limited in-house accommodation. The nurses, who were chiefly situated in villages relatively close to the city, took an average of two children each and were subject to a regime of regular inspection.

Education

Whether the children were kept in the hospital or at their nurse, they were given skills to equip them to be useful and productive citizens – a key ethos of the Founding Hospital. A ‘manufactory’ was set up in the hospital where spinning, weaving, knitting and other textile skills were learnt. Similar skills were taught to the children living with their nurse. For them, local teachers were found and paid by the hospital’s appointed inspectors. Many learned to knit there; some learnt to spin yarn. All the children, whether in the hospital or with a nurse, were also taught to read. Some – probably only selected boys – also learned to write.

Apprenticeships and life after the Hospital

After their education, many of the children were found apprenticeships. This occurred as young as age eight, although most were ten or eleven. It is noticeable how many went into quite generalised roles – domestic service, dairy farming or husbandry for example. Few were offered places to learn more specific skills, which apprentices of local origin did, such as metal-working, shipbuilding or – surprisingly, given the training the Foundlings had been given – textile work.

The London governors could be very unsympathetic in their demands. From time to time they required that children be returned from Chester to be apprenticed in the capital. One wonders why it was necessary to take them all the way from Chester for this. When Henry Maple (No. 8209), probably aged eight, was ordered to be sent to London, the Chester secretary pleaded that the child was with a good nurse who wanted to apprentice him – but still London insisted on his return. Just one child from Chester, William Courtney (No. 12540), was claimed by his parents and reunited with them in London.

Work continues to trace the subsequent lives of those who went to Chester, though it is impossible to do so with certainty for most of them. Some who were apprenticed locally got married and had ‘normal’ lives. A fine example is Sigismund Lane (No. 6480) who went on to marry locally, have five children, become a farmer and live to age 83. Mary Dobber (No. 6977), who was disabled, returned to work at the London Hospital as she could not be apprenticed. She married one of the Hospital staff.

Following the hospital’s closure, the Blue Coat School, which still stands today slightly enlarged from its time as a hospital, reverted to being a school for local children.

*Quote from: London letterbook (A/FH/A/006/002/001), 4 November 1762, letter to Trafford Barnston at Chester probably from Taylor White at the London Foundling Hospital.