Content warning: This article contains reference to sexual assault which readers may find distressing. Find more information on our Help and Support Signposting page.

Between 1747 and 1880, the Foundling Hospital admitted at least 66 pairs of twins. In the early decades, twins were given different surnames, and their relationship was only sporadically recorded. From 1767, however, the Hospital began to make careful notes of twins and baptise them with the same surname, as the stories of the Smith and Rowley twins show.

Alice and Joyce Smith

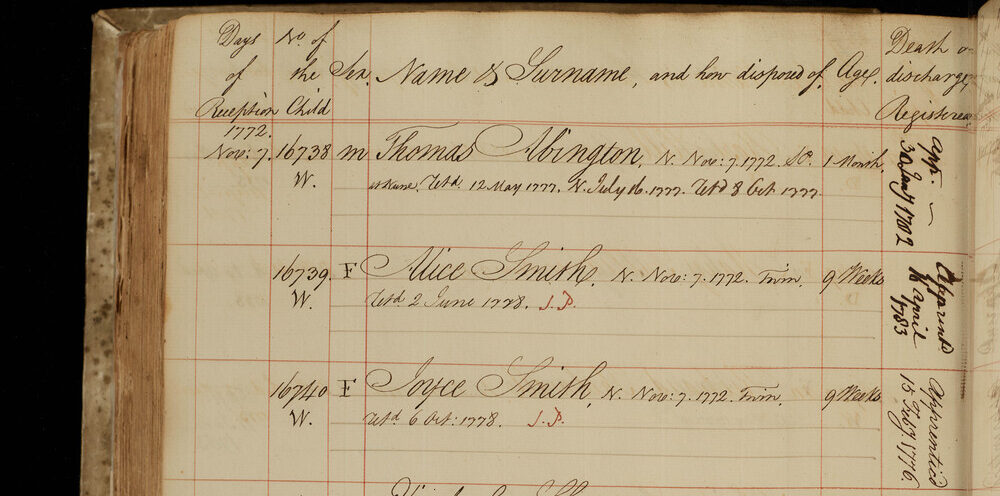

On 7 November 1772, a nine-week-old girl was admitted to the Foundling Hospital and given the name Alice Smith (No. 16739). The baby admitted just after her was also nine weeks old and baptised Joyce Smith (No. 16740). Although her petition letter is missing from Coram’s Foundling Hospital Archive, we know their mother’s name was Grace Nuttress, as it is written on both their admission billets.

Soon after their admission, the twins were sent to Harlow in Essex to be wet nursed, in the homes of different nurses. Both girls returned to the Hospital in 1778, aged six. From here onwards, they would have dined, slept, played, and attended lessons together with the other girls at the Hospital. Whether or not the staff encouraged twins to bond, their surnames and likely resemblance would have made their connection obvious. One imagines that this rare opportunity for Foundling children to connect with their biological family members would have encouraged a close relationship.

In June 1781, Alice became ill with whooping cough. The Sub-Committee minutes record that she was sent, with two other children, to live temporarily with a nurse in Finchley, London, to recover. The trip to the countryside clearly improved her health, and she returned to the Hospital three months later. Then, in April 1783, Alice went to live with her new apprentice-master. It was not uncommon during this period for children to be apprenticed as young as 11. Foundling girls largely went into domestic service, so it is notable that Alice Smith was apprenticed to George Gardiner, a pastry cook in Westminster, London, ‘to be employed in his business’.

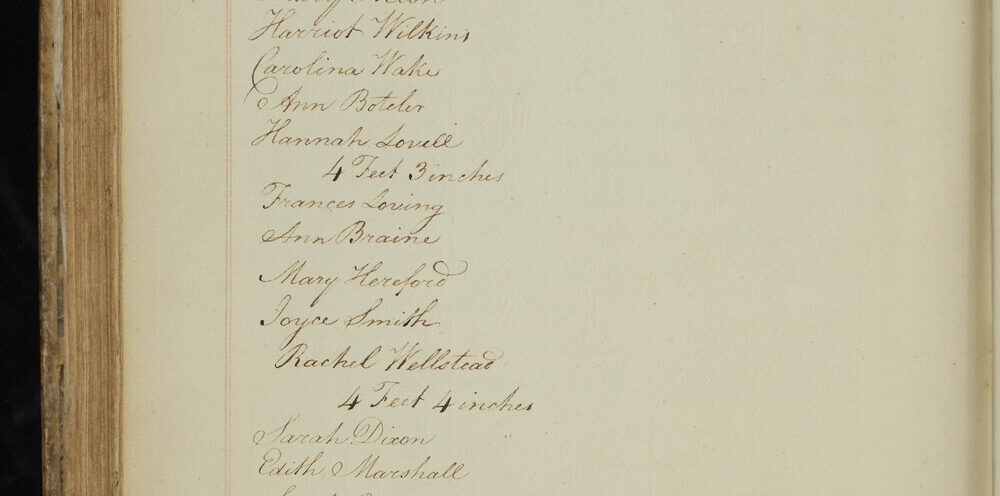

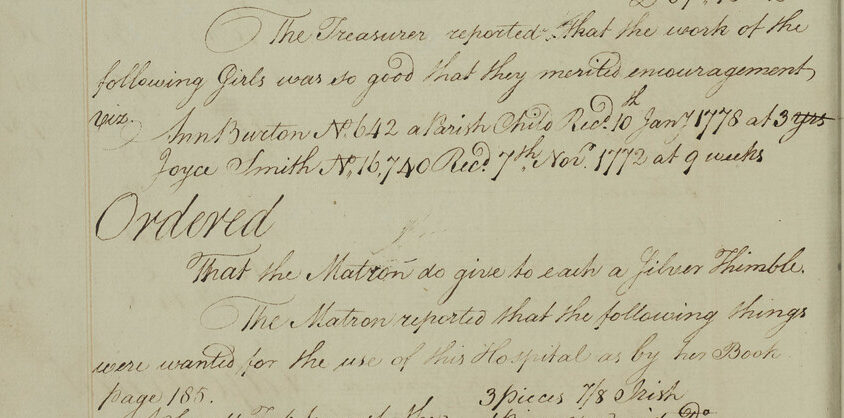

Meanwhile, Joyce remained at the Hospital for three more years. The archival records do not explain why her apprenticeship was delayed. Joyce seems to have been a talented and hardworking child. In January 1786, the Treasurer reported that ‘the work of the following girls was so good that they merited encouragement’. Joyce is one of the two girls listed, and the Sub-Committee decided that both should be given a silver thimble for their achievements. Silver thimbles were awarded as prizes to the girls who were most accomplished at sewing and mending. Perhaps it was this that proved her aptitude to the committee, as a month later Joyce was apprenticed in ‘household business’ (domestic service) to Mary Mackenzie of Upper Seymour Street in Marylebone, London.

Thomas and Frederick Rowley

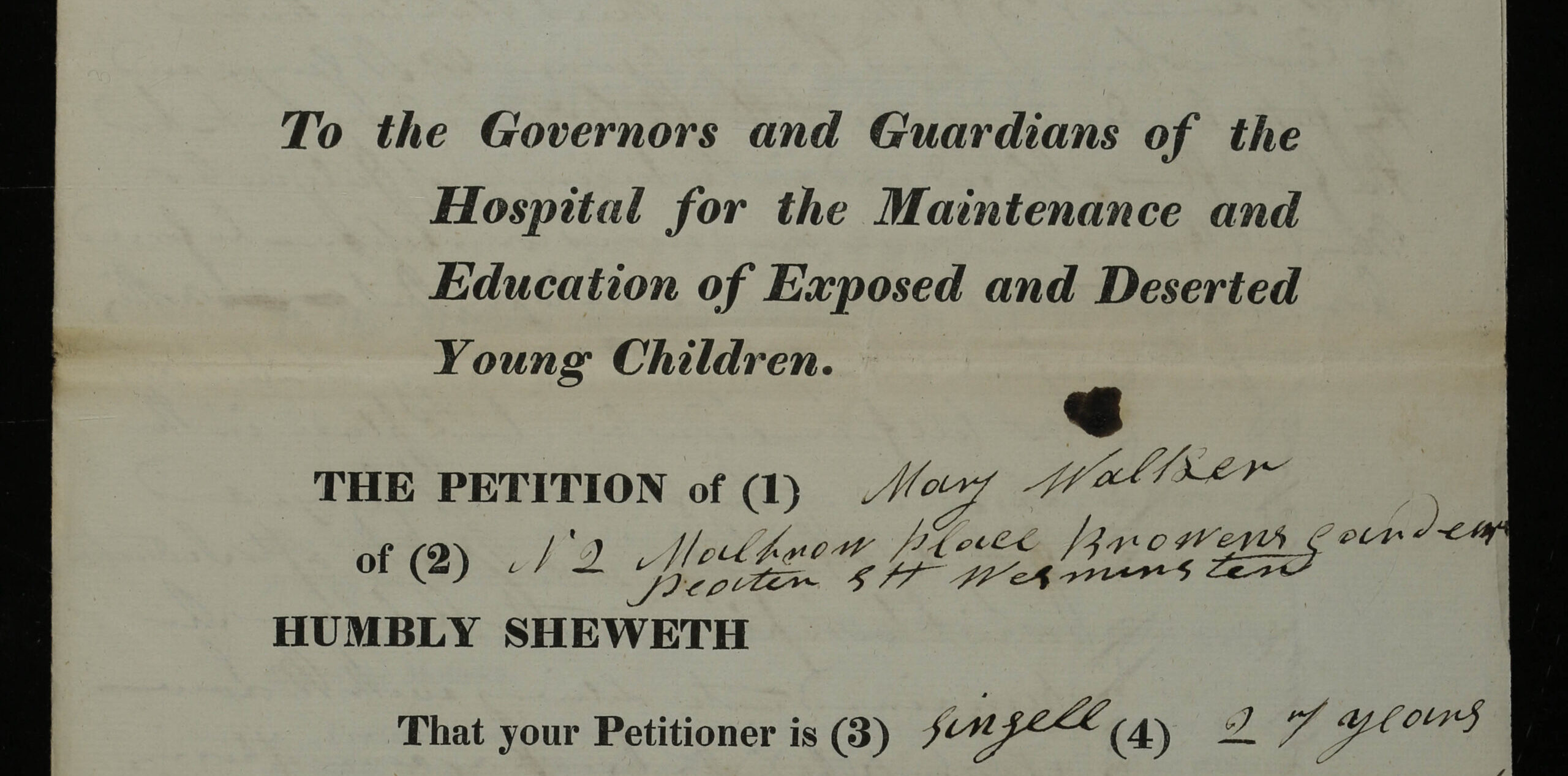

Many of the women petitioning the Foundling Hospital to accept their infants could not afford to support one child, let alone two. Mary Walker was a cook in a house on Waterloo Road, London, when she met John Green. He was the servant of a gentleman who rented some rooms in the house for three months from May 1833. In July, as Mary’s petition explains, John seduced her whilst the family was out of the house. She ‘did not tell her fellow Servants – hoping that nothing would follow.’ Unfortunately, soon after John departed with his master, Mary discovered she was pregnant. On 31 March 1834, she gave birth to twin boys. A month later, she petitioned the Foundling Hospital, explaining that her employer would keep her on if her sons were accepted.

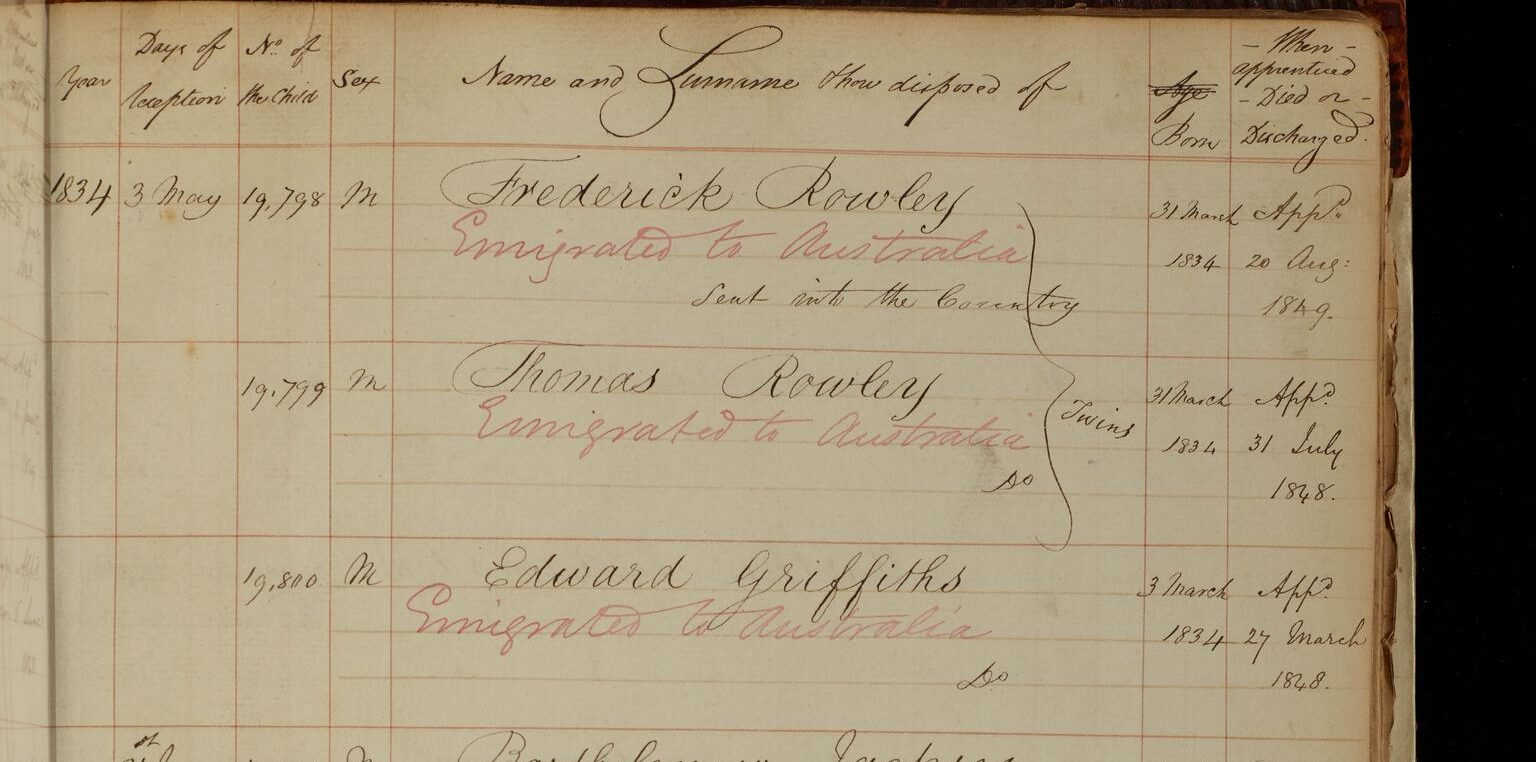

The Hospital admitted Mary’s twins in May 1834 and named them Frederick and Thomas Rowley (No. 19798 and 19799). They were sent to nurse in the countryside and, according to the 1841 census, both had returned to the Hospital by the age of six.

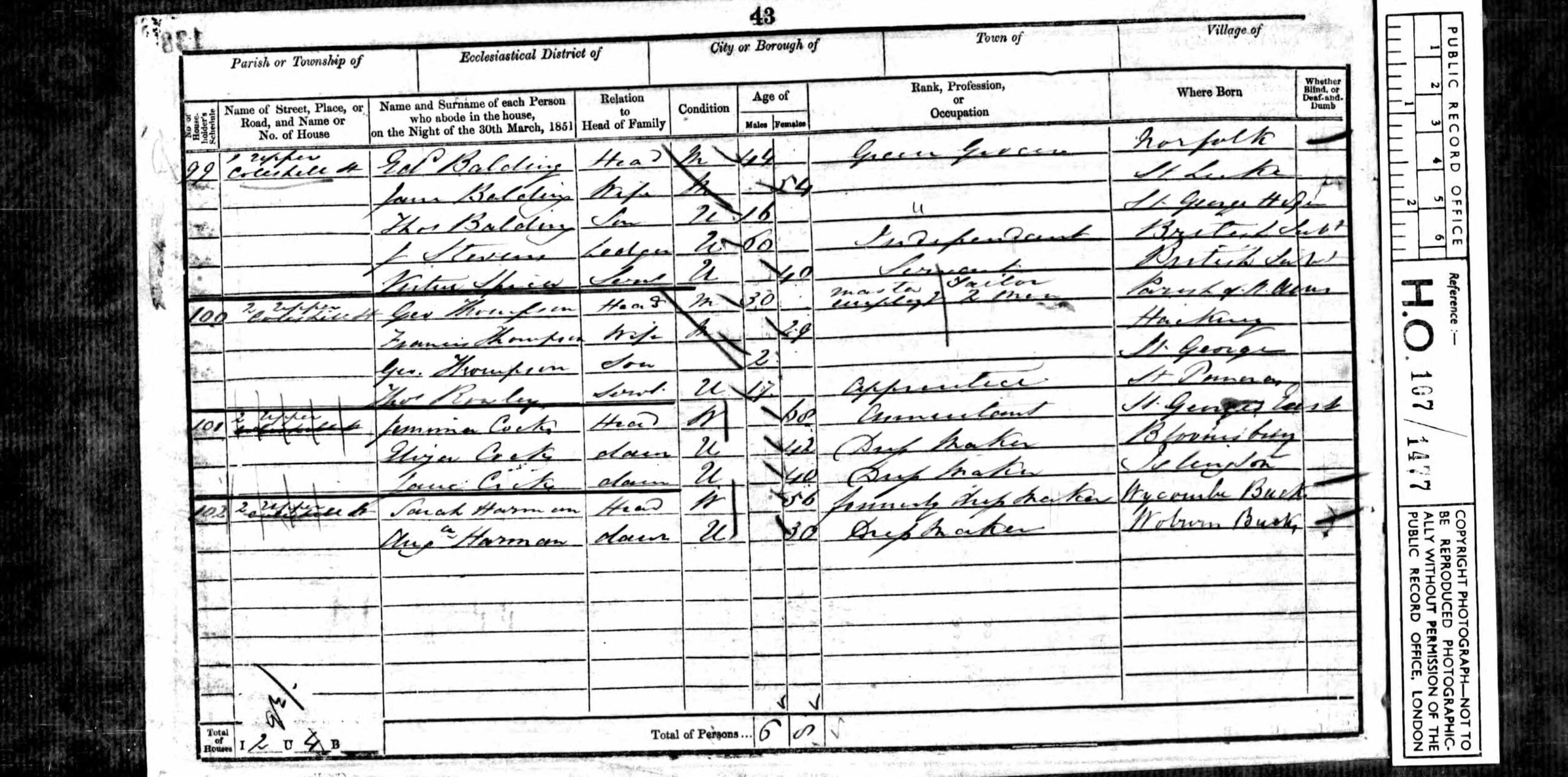

In July 1848, aged 14, Thomas was apprenticed to a master tailor named George Thompson and went to live in Upper Coleshill Street, London, with George, his wife, and their two-year-old son. Thomas seems to have worked hard at his trade, as the Hospital received glowing reports. The last report was in 1852 when George stated that ‘Thomas Rowley conducts himself very well and improves greatly in his business.’

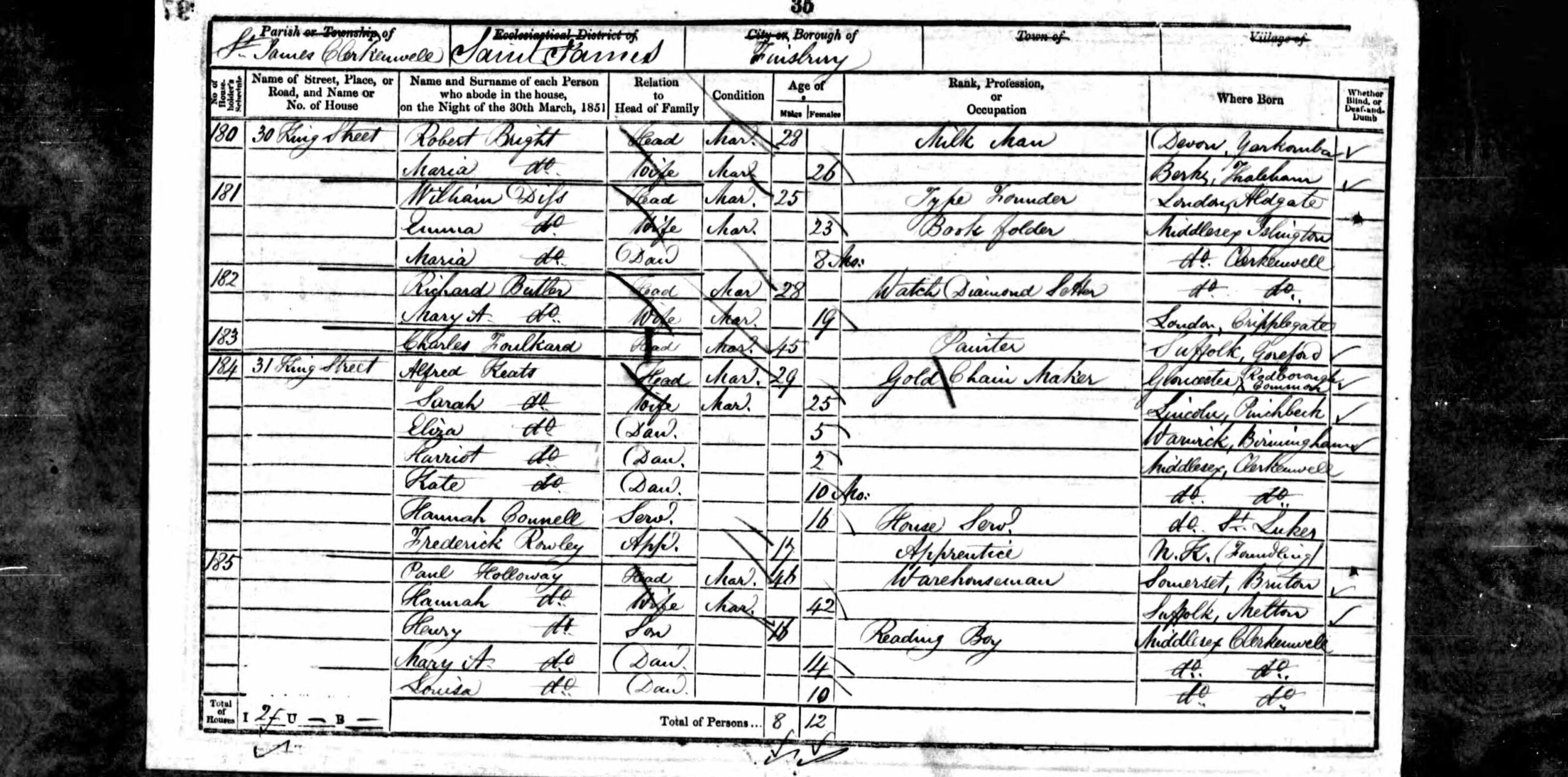

In 1849, Frederick was apprenticed to Alfred Keats, a gold chain maker who lived in Clerkenwell, London, with his wife and three daughters. Both boys were indentured to their masters until the age of 21. However, in November 1851, the General Committee minutes reveal that Frederick had complained to John Brownlow, the Hospital Secretary, of his master’s ‘gross cruelty towards him’. The Hospital removed Frederick from his master’s house and took legal action against Alfred, who was ordered to return the money he had received when he took on his apprentice.

Frederick was transferred to a new master, Charles Searle of Shoreditch, London, to be trained as a cooper (someone who makes wooden barrels). Thankfully, Frederick seems to have been much happier there. He received good testimonials from Charles, who reported that ‘Frederick Rowley has conducted himself in a proper manner during his apprenticeship… I have no fault to find and he is still with me.’ Frederick was awarded a gratuity of 5 guineas in April 1855, on the completion of his apprenticeship.

The Foundling Hospital’s records for each child generally conclude with their discharge at age 21. For the Rowley twins, however, the archive holds some additional clues about their lives beyond the Hospital. In December 1855, Frederick wrote to John Brownlow thanking him for ‘the money you was kind enough to lend me’ and informing him that ‘I am about to start to Australia’. The Hospital records have a note stating ‘emigrated to Australia’ next to not just Frederick’s name, but Thomas’s as well. Investigation of ships bound for Australia reveals that Frederick appears on the passenger list of the ‘Amazon’, sailing to Adelaide on 1 January 1856. His age is listed as 21 and his occupation as cooper.

Three years earlier, in August 1853, a 19-year-old Thomas Rowley appears on the passenger list of the ‘Plantagenet’, which left from London for Sydney. As Thomas’s apprenticeship reports drop off after 1852, it is possible that Thomas negotiated an early discharge from his apprenticeship in order to seek his fortune overseas. Indeed, if this is the same Thomas Rowley, it would explain why Frederick made the decision, three years later, to emigrate to Australia: to join his twin brother.