Lydia is doing a history-focused internship on Coram’s Voices Through Time: The Story of Care Programme, made possible by the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

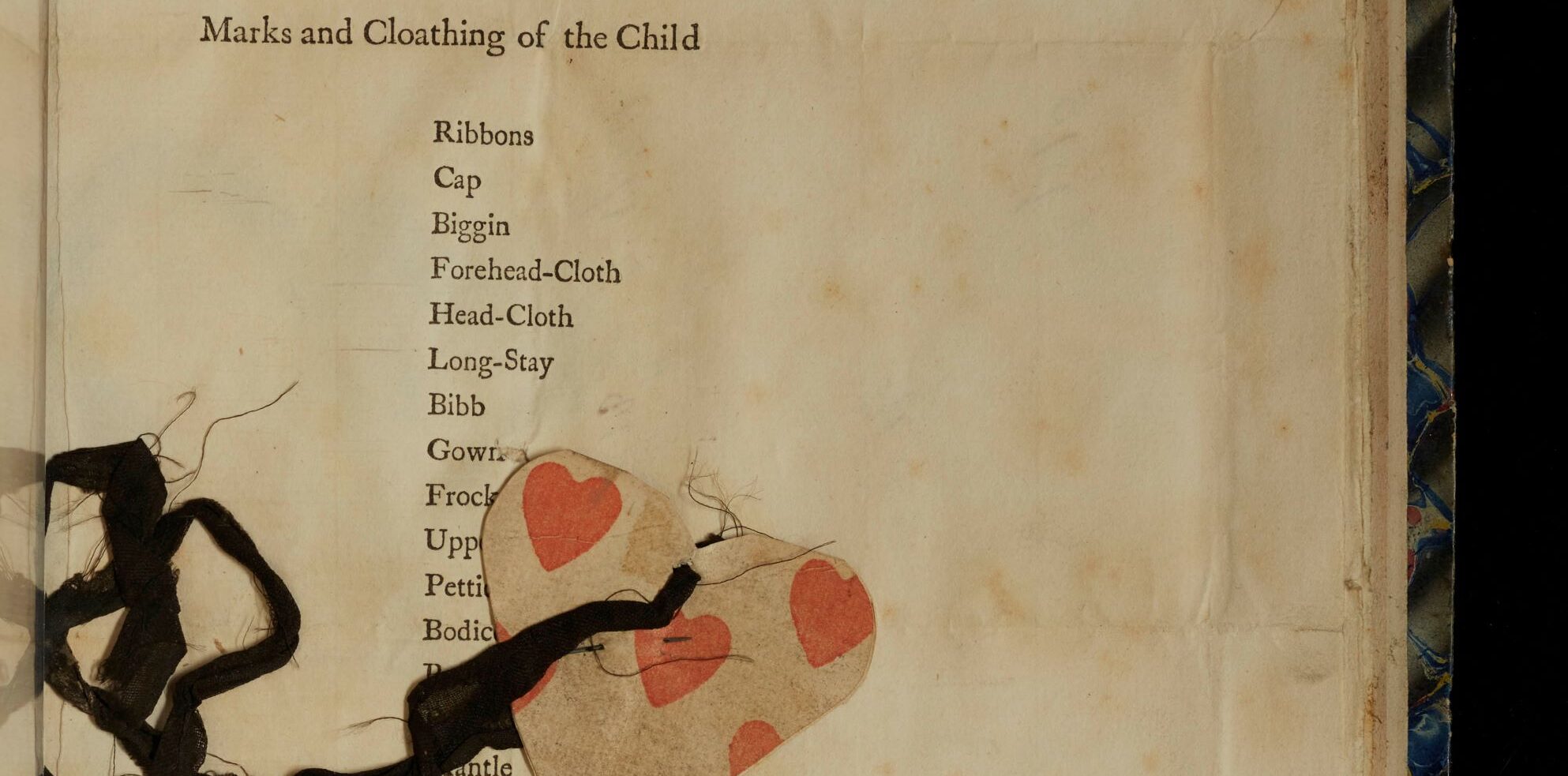

After its founding in 1739 by Thomas Coram, the Foundling Hospital proceeded to look after 27,000 children. The Hospital’s work was meticulously recorded and preserved, surviving today as Coram’s vast Foundling Hospital Archive. The purpose of the Voices Through Time programme, and of my role as Heritage Engagement Intern, is to engage people with this fascinating history. We are doing this by developing a digital archive and through creative projects with care-experienced young people.

Developing the digital archive

A key purpose of my role is preparing the content for Coram’s online digital archive, which will provide free access to nearly 100,000 digitised records from the Foundling Hospital Archive, stretching from 1739 to 1898. To accompany the digitised records, we are creating transcripts of each page, and proofing those produced remotely by our wonderful volunteers. These transcripts will not only help with deciphering archaic spellings and handwriting, but ensure key information in the archive is searchable, saving users from clicking through thousands of pages to find what they are looking for.

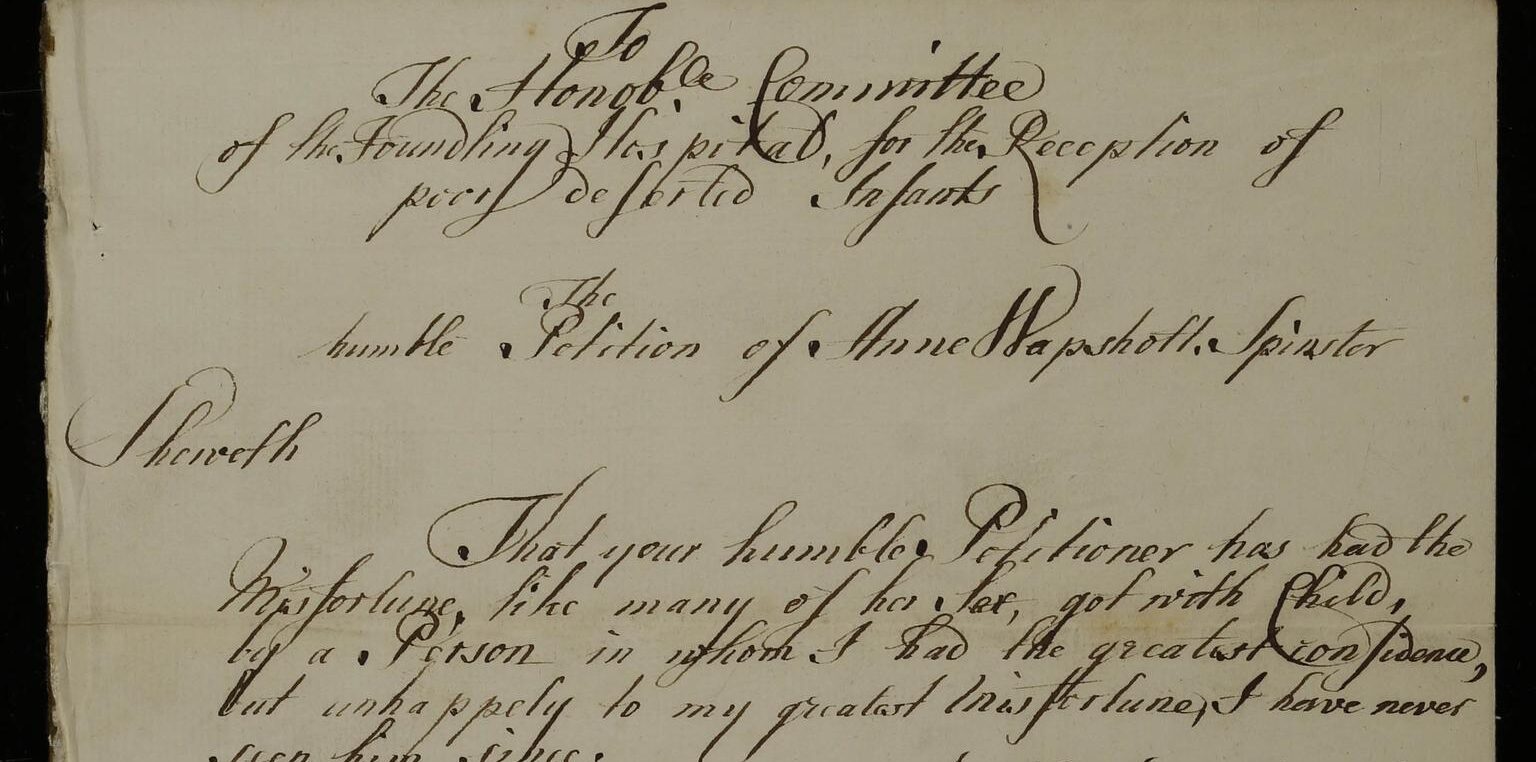

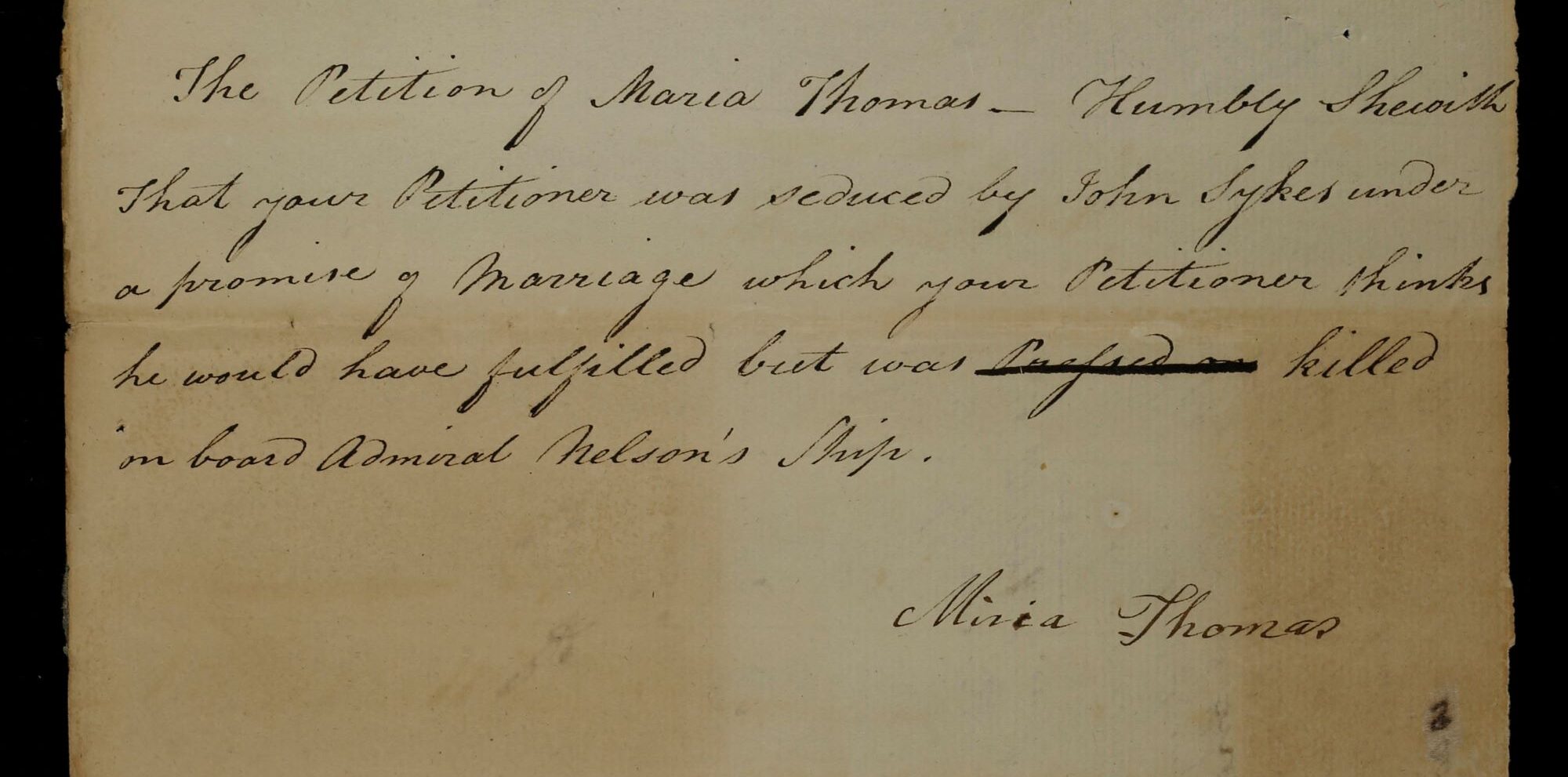

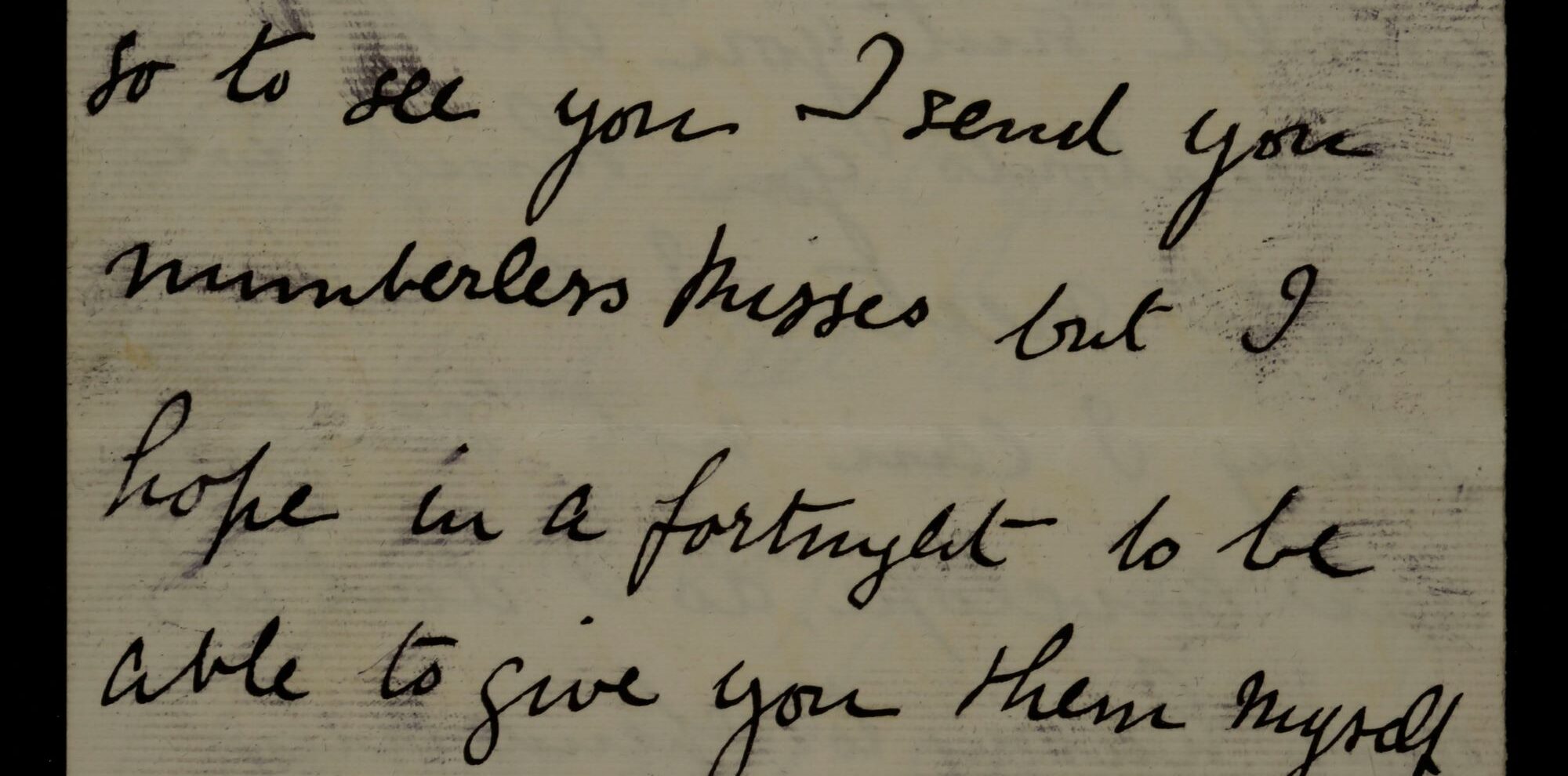

My favourite section of the archive is undoubtedly the Mothers’ Petitions. These letters and statements detail the cases put together by mothers asking the Hospital to admit their infants, of which 35,295 pages have been digitised. The stories within these documents are extraordinary and heartbreaking. When so much female experience, throughout history, has gone unrecorded, these pages provide a source for some of the most complicated, emotional, and intimate moments of human existence, recorded largely in the women’s own words.

“The stories within these documents are extraordinary and heartbreaking. When so much female experience, throughout history, has gone unrecorded, these pages provide a source for some of the most complicated, emotional, and intimate moments of human existence…”

Across these pages, I have been equally enthralled by glimpses of the extraordinary and the everyday. I have read many juxtaposed descriptions of birth, death, wedding days, and voyages (one, recently, aboard a ship captained by Admiral Nelson). Letters containing ‘numberless kisses’, pleas, advice, and book recommendations sent across continents; sickness, destitution, cruelty, and unexpected kindness. In true English fashion, I also found many reflections on the weather. The only problem with working on this section is that I am constantly pausing to reread passages and make frenzied notes, which slows the process down a little.

Elsewhere in the archive, I have been working closely with the Billet Books and the General Registers to produce spreadsheets combining the information they provide for each child. The result will be a comprehensive index of key information for the 22,000 children admitted between 1741 and 1885, which should make searching for specific children much easier. At first, I did find dealing with this much information slightly mind-boggling. However, there is something wonderful about combining the meticulous record-keeping of previous generations with the data-manipulation tools available to us, to ensure these records continue to survive.

Exploring the archive

Another remarkable thing about working with Coram’s Foundling Hospital Archive is that its ‘completeness’ allows you to conduct both broad and deep research without leaving its boundaries. I have used the digital archive extensively to research articles for the Coram Story website and content for the resource pack we released alongside our theatre project, Echoes Through Time. When I was writing an article about the Hospital’s system of nurses and inspectors, I used the Inspection Register for 1749-1758 to calculate that 40% of inspectors for that period were women. I was able to combine this quantitative study with documentary evidence from other sections of the archive to demonstrate that the Hospital’s inspectors were an early example of men and women working alongside each other, and receiving equal recognition for their contribution.

As a history undergraduate, I often felt like there was nothing left to study that had not already been picked apart by generations of historians. It has been really eye opening to work so directly with primary sources, and to realise that there is still much to be discovered. Recently, whilst working with the archive, I have been fascinated by a double-standard I have observed in 18th- and 19th-century English ‘morality’. Whilst notions of hereditary ‘bad blood’ were widely upheld (and incredibly damaging to unmarried mothers and their children), respectable families routinely employed unmarried women who had recently given birth to breastfeed their children. I am keen to conduct more research into this contradiction.

Engaging with the archive

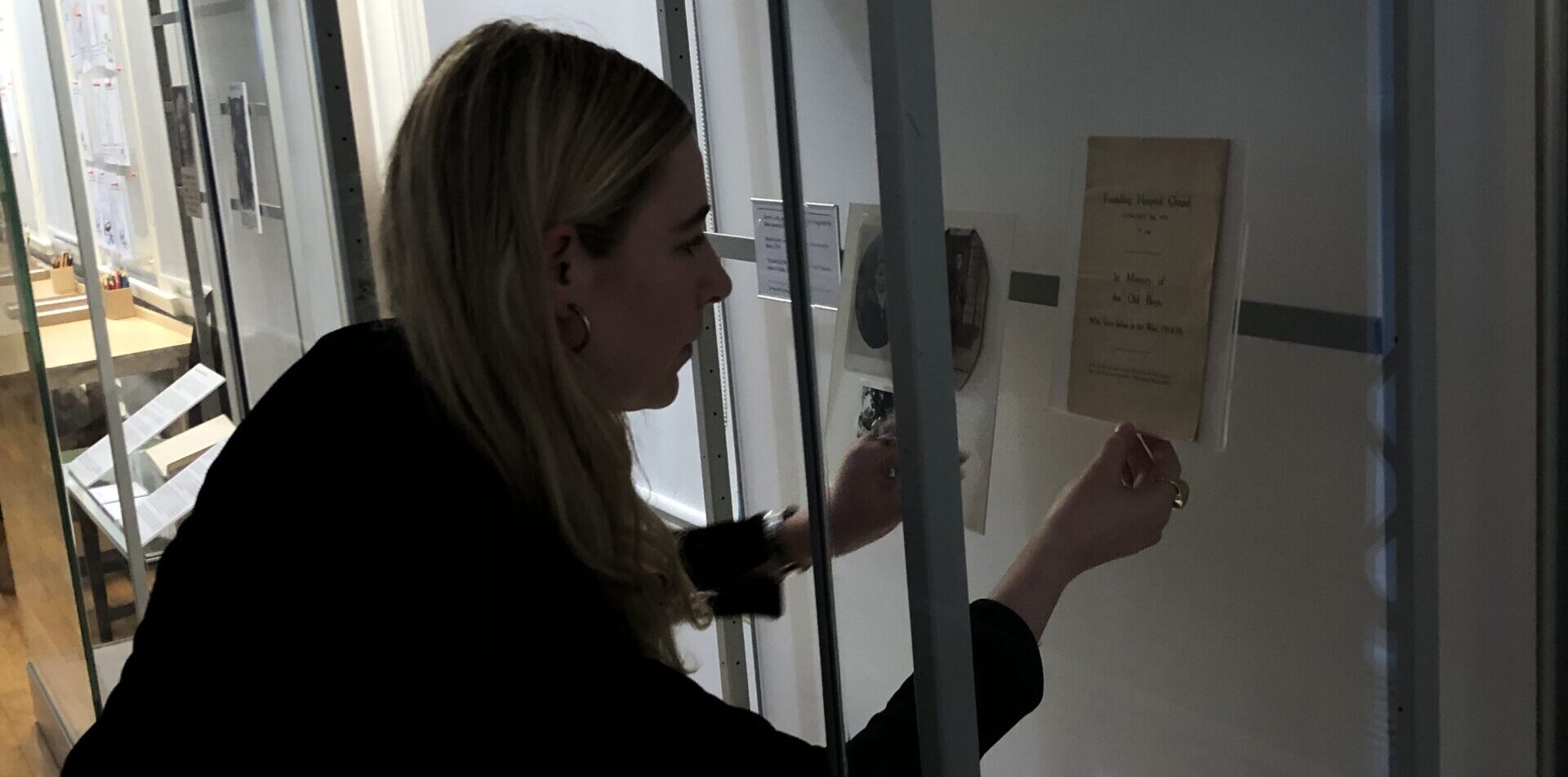

Working on this project has made me think a lot about the study and purpose of history, and the way ‘the past’ is constructed by what has and has not survived. During a study day I attended with the Association of Performing Arts Collections, I was particularly struck by a discussion about the role archives play in alleviating the burden on individuals, particularly from marginalised communities, to ensure their history is not forgotten and their experiences survive them. I thought a lot about this responsibility when I was lucky enough to curate a display about two former pupils (using items donated by their children and grandchildren) during a placement at the Foundling Museum.

Working with and around Coram’s archive, I am aware of the serendipity that these fragments of the past have survived whilst countless others have perished. I am also conscious that preserving the past is not a purely material feat. Equally important as the archive’s physical survival is that these stories continue to be thought of and spoken about. It has been really interesting to assist on the programme’s creative projects surrounding the content of the archive. In May, I supported the rehearsals of Echoes Through Time, an original play exploring stories from the Foundling Hospital in parallel with modern experiences of care. Witnessing the way the young participants interacted with the historical content of the play, I felt an overwhelming sense of the archive’s relevance and permanence, which further grew as I discussed the play with audience members afterwards.

“I am aware of the serendipity that these fragments of the past have survived whilst countless others have perished. I am also conscious that preserving the past is not a purely material feat. Equally important as the archive’s physical survival is that these stories continue to be thought of and spoken about.”

Voices Through Time is such an exciting programme to work on. Not only does digitisation reinforce the physical survival of historical sources, but the digital archive, as I have seen with our creative projects, will continue to bring this incredible part of history to many new and varied audiences, whose thoughts and conversations are so vital to its endurance.

Copyright © Coram. Coram licenses the text of this article under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 (CC BY-NC).