My interest in family history was sparked off by a family story that we were descended from King George III, albeit, on the wrong side of the blanket. Tracing my father’s line back I found Hannah Fitzgeorge, my 2x great grandmother. It was exciting to find the name Fitzgeorge with its royal associations. Fitz was a prefix used for the surnames of illegitimate children of kings, and George III was rumoured to have had a liaison with Hannah Lightfoot, a Quaker. So, with a name like Hannah Fitzgeorge, there was hope of a royal lovechild amongst my ancestors.

Hannah Fitzgeorge was baptised in 1792 in Warmsworth, near Doncaster, South Yorkshire. She was the daughter of Edmund and Hannah Fitzgeorge. Edmund was a blacksmith, which did not seem an appropriate profession for the son of a king. I searched all surrounding parishes and many genealogical indexes, but Edmund remained a ‘brick wall’ for many years. He seemed to have appeared from nowhere. Then, through a fellow researcher, I discovered that a baby boy with the name Edmund Fitz-George was given into the keeping of the Foundling Hospital, at about the right time – eureka!

Edmund’s early life

Once I had found Edmund, I discovered a wealth of information in Coram’s Foundling Hospital Archive. My 3x great grandfather was received into the Hospital on 10 April 1758 at the time of the General Reception, when all infants handed into the Hospital were accepted.

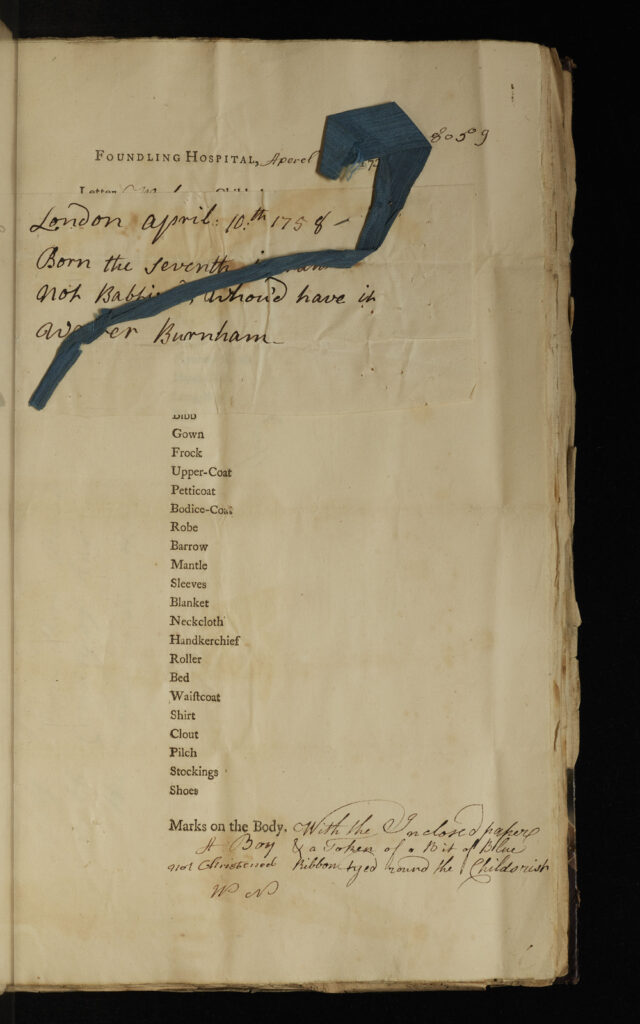

On receiving the child, the Hospital used a printed billet form to list key information about the infant. Although Edmund’s billet does not detail the clothing he arrived in, it does have a handwritten note pinned to it. The note reads: ‘London April 10th 1758 – Born the seventh instant – Not baptized; Whould have it Walter Burnham’. A piece of dark blue ribbon is also pinned to the billet. It was left as a token should his mother ever wish or be able to retrieve her son.

- Edmund’s billet: A/FH/A/09/001/092/123. Click to enlarge.

On a visit in 2005 to London Metropolitan Archives, where the Foundling Hospital Archive is housed, it was an emotional experience for me as I touched the token. It was poignant to think that I was probably the first family member to see those mementoes in 250 years and that Edmund himself never knew of their existence.

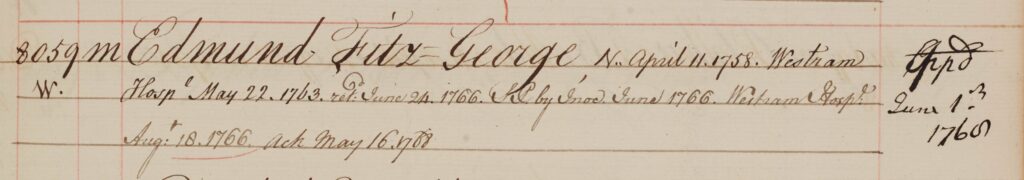

Once admitted, Edmund was baptised, given the number 8059, and put in the care of a wet nurse, Elizabeth Cockerill of Chiddingstone, Kent. Elizabeth and her husband Henry already had children of their own; so, for his first five years, Edmund lived as part of this family. Then, in May 1763, he was sent to the Westerham branch of the Foundling Hospital in Kent.

Edmund’s entry in the General Register: A/FH/A/09/002/002/455

At the branch hospitals

Going to the Westerham Hospital must have been heart wrenching for both Elizabeth and young Edmund. He was leaving the only home he had ever known to be part of a strict institutional regime. I found in the Westerham Foundling Hospital records that Henry Cockerill was sometimes employed there to mend the spinning wheels. I like to think that he kept his eye open for Edmund when he visited and maybe Elizabeth too managed a peep, although this was not encouraged by the hospital.

Edmund would have been taught to read so that he could read the Bible, as this was thought important, but not to write. Edmund put a cross when he signed the parish register at his marriage as he could not write his name.

In the summer of 1766, Edmund spent nearly two months at the London Foundling Hospital, where he was inoculated against smallpox. Then he returned to Westerham.

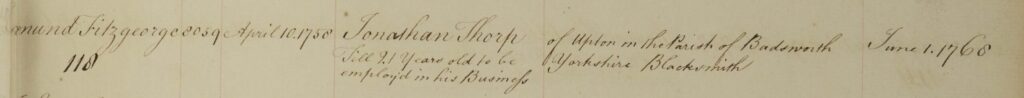

He grew into a tall boy. I know this because in 1768, John Saunders, secretary of the Westerham branch, received a letter asking for 16 of the tallest boys to be sent up to London, from where they would be apprenticed. Therefore, in May 1768, Edmund was sent to the Ackworth branch hospital in Yorkshire. On 1 June 1768, aged 10, he was apprenticed to Jonathon Thorp, the blacksmith of Upton, near Badsworth, West Yorkshire. Jonathon was paid £3 guineas to take him on, and Edmund was apprenticed until he was 21 years old.

Edmund’s entry in the Apprenticeship Register: A/FH/A/12/003/001/167

Marriage and later life

Edmund was incredibly fortunate to be apprenticed to Thorp because, again, he was part of a family. Jonathon’s son, Joseph, was one of the witnesses at Edmund’s marriage.

Edmund married Hannah Mason, a stone mason’s daughter, on 4 October 1785, four years before his apprenticeship was officially complete. I think Jonathon looked favourably on Edmund, allowing him to marry, probably because Hannah was pregnant. Their first child, Mary, was born four weeks later.

At the time of Mary’s baptism, they were still living in Upton but moved to the smithy in Warmsworth where their second child, John, was born less than two years later. Of their 12 children, all but two grew up to marry and have children of their own.

After his apprenticeship, Edmund worked as a blacksmith on Sheffield Road, Warmsworth, the busy mail road between Doncaster and Sheffield. Some of his descendants followed in that profession in nearby Balby until the 1930s. Remarkably, the building that was the Warmsworth smithy is still there, although converted to a shop now.

I have an article from the Doncaster Chronicle, passed down through the family, which records the memories of his grandson George under the title; ‘The Fitzgeorges: A Remarkable Family’. It gives an account of Edmund working in knee-length breeches as a blacksmith. The article says:

“He had to his knowledge, not a relation or friend in the world. He had been at a foundling school in or near London, and while there had been sometimes visited by two ladies, one of whom took great interest in him and always appeared much effected when leaving him.”

Edmund believed this could have been his birth mother, but I think that it was his former nurse, Elizabeth Cockerill, perhaps with one of her daughters. I have another newspaper cutting that confirms the family’s belief in a royal father.

Unusually, a census for Warmsworth was taken in 1829. It lists Edmund Fitzgeorge, aged 72 years, wife Hannah, and grandchild Richard, 5 years. Edmund and Hannah both died in 1835 and are buried together, along with their eldest child Mary, who died at age 17. The gravestone is still there in Warmsworth.

Edmund and Hannah had at least 62 grandchildren. I have been in contact with several of their descendants scattered all over the world. Some had the same tale of royal descent. I have discovered that descendants of other Foundlings have the same family legend. Perhaps their nurses told the children these stories to make them feel better about their lowly beginnings.

So, looking at all the evidence there is nothing to prove a kingly dalliance. I must accept that I probably will never find the truth of Edmund’s parentage. The name Walter Burnham written on the note is the best clue I have. However, I will continue to search and maybe one day with a DNA match I may find out more about Edmund’s beginnings. After all, the true story of Edmund Fitz-George and the Foundling Hospital is just as interesting.

Bibliography

Billet: A/FH/A/09/001/092/123

General Register: A/FH/A/09/002/002/455

Nursery Book: A/FH/A/10/003/005/204

Westerham Register: A/FH/A/10/008/001/016

Ackworth Register: A/FH/A/10/006/001/080

Apprenticeship Register: A/FH/A/12/003/001/167